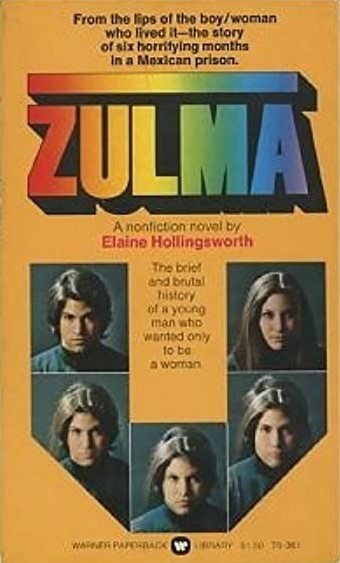

By ELAINE HOLLINGSWORTH (Warner Books; 1974)

By ELAINE HOLLINGSWORTH (Warner Books; 1974)

A quintessentially seventies artifact that combines two of the decade’s most popular themes: prison and gender dysphoria, resulting in a sensation-packed concoction that reads like MIDNIGHT EXPRESS crossed with LET ME DIE A WOMAN. Sign me up!

The author was 1950s starlet-turned-celebrity home flipper-turned-alternative medicine pusher Elaine Hollingsworth (a.k.a. Sara Shane), whose first book this was. She calls Zulma a “nonfiction novel,” with a preface informing us that its title character, a pre-op transsexual, was real, and the broken English related first person narrative (“to best capture the personality of this strange creature”) taken from conversations with Zulma about her life (although “there were places where I had to novelize the story”). The author’s initial intention was apparently to write an expose on Mexico’s notorious La Mesa prison, but upon coming into contact with Zulma, “one of the most remarkable and touching and unfortunate human beings you will ever meet,” Hollingsworth decided to narrow her focus.

The book opens with eighteen year old Zulma, a.k.a. Miguel, on her way to meet a Tijuana doctor for sex reassignment surgery. Before she can do so she’s nabbed by cops for public intoxication and, following an altercation, given a six month sentence in La Mesa.

This place, we learn, is different from most first world prisons, being essentially a mini-city in which the inmates are allowed to roam free. Of course the “law” in this community is that of the jungle, with brutality, intimidation and rape being constants. Zulma experiences all those things, and in great abundance. Not that this is much of a change from her earlier life in Acapulco and Los Angeles, marked by grift, prostitution and short-lived marriages to men who, Zulma assures us, were more often than not shocked when she revealed that she wasn’t born female. The book concludes with Zulma being released from La Mesa and, it seems, poised to fulfill her lifelong ambition of getting a sex change and nabbing a rich spouse. The final page, however, informs us that two weeks after Zulma’s release her stab wound-ridden corpse was found in Tijuana, with her assailants, and their motives, unknown.

With ZULMA Elaine Hollingsworth announced herself as a gifted novelist. The book is economical and compelling despite the rambling non-narrative, and the fractured English-laden prose (“She tell me to come over to her house so I can paint myself and fix myself there and I tell her I got butterfly in the stomach”) is pulled off with a great deal of authorial flair, feeling off-putting at first but, in true CLOCKWORK ORANGE and RIDDLEY WALKER fashion, growing increasingly harmonious. As seventies-centric exploitation the novel succeeds admirably, with one or more new outrages on every page and a convincingly detailed subterranean milieu.

It’s all held together by Zulma herself, an altogether unique and multi-faceted individual. She comes off as well-intentioned and heroic, but also bitchy and, in some portions, racist. That last point would likely render ZULMA unpublishable today, but I applaud Hollingsworth’s rendering of this character’s complicated mental state, politically incorrect though it may be.