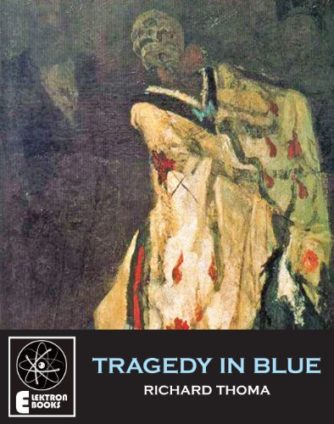

By RICHARD THOMA (Elektron Ebooks; 2012)

By RICHARD THOMA (Elektron Ebooks; 2012)

The fearsome figure of the 15th Century French child killer Gilles de Rais continues to exert an enduring fascination. Rais was a fiercely multifaceted individual, fighting alongside Joan of Arc as a commander in the French army and later dabbling in necromancy and the occult before killing dozens, possibly even hundreds, of children prior to being executed in 1440. Gilles de Rais is said to have inspired the figure of Bluebeard in the Charles Perrault fairy tale of that name, as well as a fair amount of novels, including J.K. Huysmans’ 1891 classic LA BAS, Michael Tournier’s GILLES AND JEANNE, Edward Lucie-Smith’s THE DARK PAGEANT and Richard Thoma’s TRAGEDY IN BLUE, a novella that occupies a niche of its own.

Unlike its fellows, Thoma’s account takes a highly florid and poetic approach that places Rais’ unquiet psyche at the forefront. TRAGEDY IN BLUE, I should add, was quite obscure prior to 2012, having previously appeared in a limited edition of just 100 copies in Paris back in 1936 (if the book was known at all it was for an enthusiastic write-up by Henry Miller and the references made to it in Georges Bataille’s nonfiction tome THE TRIAL OF GILLES DE RAIS).

Thoma’s narrative follows the particulars of Rais’ life fairly closely, but again, his is a psychologically centered account less concerned with historical detail than with its subject’s ever-shifting mental state. It begins with Rais as a young adult, joining the cause of Joan of Arc. He’s immediately struck by her boyish figure and near-messianic conviction, yet has a presentiment that she’s not long for this Earth. He grows perversely determined to be the Judas to Joan’s Christ, yet when she’s executed Rais is devastated, and turns to the beliefs of his pagan ancestry for solace. It’s this aspect, the author argues, that led to Rais’ downfall, as “from ecstatic mysticism to the exaltations of Satanism is but a grave earthstep.”

Rais’ subsequent descent into murderous insanity is carefully and convincingly laid out. Thoma’s claim is that the androgynous figure of Joan, and Gilles’ betrayal of her, directly informed his career as a child murderer. Those murders are portrayed with fairly graphic (but never gratuitously so) detail; this isn’t a splatterpunk treatment by any means, but nor does it shy away from the ugly particulars of Rais’ madness.

The most disturbing portion of the novel arguably occurs in the final pages, in which Thoma alleges, without a trace of irony, that Rais’ newfound religious conviction fully redeems him in the eyes of God. Truly, if any human being can be said to be irredeemable it’s Gilles de Rais, and I’m not sure that Richard Thoma, despite the undeniable beauty of his prose and keen psychological insight, makes a very convincing case for the contrary.