By ROLAND TOPOR (Peter Owen; 1968)

By ROLAND TOPOR (Peter Owen; 1968)

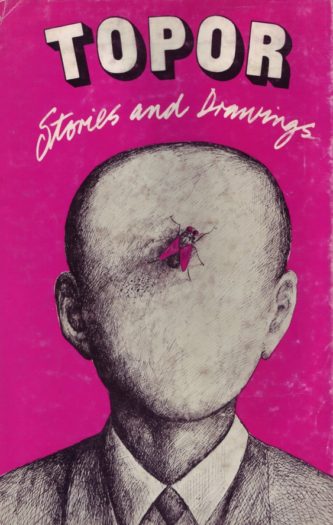

An unheralded but important volume, this, as it was the first-ever English language collection of stories by France’s late Roland Topor, whose brand of macabre satire remains quite distinct. That satire is on full display in TOPOR: STORIES AND DRAWINGS, which unfortunately also showcases Topor’s shortcomings as a prose stylist.

Rendered in notably affectionless prose, Topor’s brand of absurdism is akin to those of Roald Dahl and Fernando Arrabal (with whom Topor co-founded the famed avant-garde Panic Movement). At their best Topor’s stories transcend their surface-level gross-out humor, as in “The Blue-Eyed Boy,” about a pathologically timid man’s attempt at asking his boss for a raise, and the outrageous and ultimately horrific upheavals that result. It stands as a potent exploration of social anxiety, and contains some quintessentially Toporian imagery (such as a surreal description of the protagonist buried in “a morass of bloodstained banknotes”).

Of a similar hue is “Wrong Number,” about a man who’s given a reprieve from his solitary life—or so he thinks—when he gets a telephone installed in his apartment. The resulting outrages are sufficiently uproarious and grotesque, but also quite wise in their explication of the paranoia and apprehension that overtake the protagonist.

Twist endings are a constant, giving the tales a vaguely TWILIGHT ZONE-ish feel. Alas, not all of those endings work: see “A Delicate Operation,” which concludes with the none-too-revelatory revelation that a man undergoing radical surgery has died on the operating table. Yet some of the conclusions are quite strong, as in “The Liberators,” wherein cosmonauts on a distant planet attempt to free humanoid creatures shut up in cages–although the wholly unexpected conclusion reveals otherwise. A couple of the tales even have happy endings, although Topor’s vision is inescapably mordant for the most part.

Some of the stories are little more than half-page sketches, such as “To Godliness,” about what occurs when a heavily made-up girl washes her face. Others are decidedly lacking in maturity: see “Christmas Story,” featuring a gay rapist (indicated by the fact that he slurs his words) impersonating Santa Claus in a tale that reads like a thirteen year old’s attempt at shocking his elders.

Also included are 32 pages of drawings by Topor, in which his absurdist aesthetic is given visual form in characteristically surreal and scatological fashion. The mind-bending images on display include a man’s face literally crushed by a fist, a woman’s forehead pierced by a falling leaf, a man choking on a giant tooth, an indistinct individual climbing a ladder situated between a giant woman’s legs, etc.