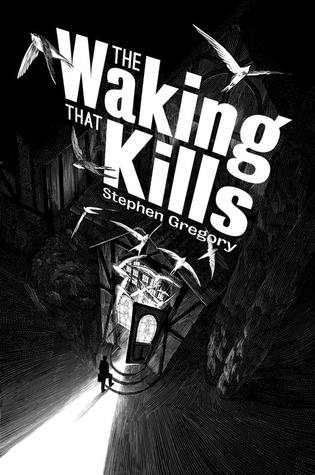

By STEPHEN GREGORY (Solaris; 2013)

By STEPHEN GREGORY (Solaris; 2013)

A highly atmospheric, solidly written horror novel that left me cold. It seems wrong to criticize a book as literate as this one, especially since the author’s previous works include THE CORMORANT and THE WOODWITCH, in my view two of the finest horror novels of the eighties, but it’s an unfortunate fact that THE WAKING THAT KILLS is simply not very successful.

The story involves Christopher, who’s just returned to his native England after teaching in Borneo. His father has suffered a stroke, leaving him adrift. In this state Christopher answers an ad for a live-in tutor for Lawrence, a severely troubled teenage boy. Lawrence has a history of violence, and has been further traumatized by the inexplicable disappearance of his military pilot father. His mother Juliet keeps Lawrence secluded from the world in their pastoral house, which only furthers his mental problems.

Christopher finds his own mental state deteriorating after moving into this madhouse. He unwisely enters into a torrid affair with Juliet, which does nothing to help Lawrence’s problems. But then, it seems those “problems” may go a bit deeper than is initially apparent, with Christopher coming to suspect that the spirit of Lawrence’s father is afoot, and possibly even possessing the body of his son.

A decent enough set-up, but it’s related in a curiously wobbly, start-and-stop fashion. A front page blurb for THE CORMORANT, dubbing it “A first class terror story with a focus that would have made Edgar Allan Poe proud,” adequately singles out what’s wrong with THE WAKING THAT KILLS, as focus is something you won’t find herein.

Repetition is another problem, with each chapter essentially repeating the same succession of events: Christopher grows apprehensive about the unhealthy atmosphere surrounding him and suffers horrific nightmares while Lawrence acts out in violent and/or inappropriately sexual ways and Juliet accepts it all with a disturbing nonchalance. The whole thing reads more like a collection of short stories than a proper novel, and ends with a brutal but unsatisfying burst of out-of-left-field nastiness.