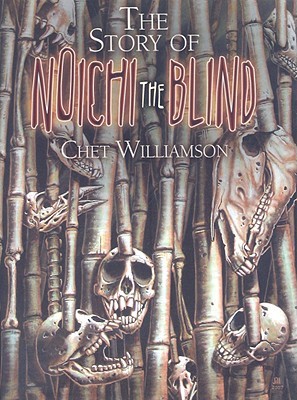

By CHET WILLIAMSON (Cemetery Dance; 2007)

By CHET WILLIAMSON (Cemetery Dance; 2007)

Here’s something unique: a novella, penned by veteran horror scribe Chet Williamson, written in the style of the late Lafcadio Hearn. In fact, it purports to be an actual manuscript by that author, complete with an introduction attesting to that “fact” and an afterward disputing it. Hearn (1850-1904) was a Greek-born writer who relocated to America and eventually Japan, where he authored several collections based on classic Japanese ghost stories, the best-known being 1904’s KWAIDAN: STORIES AND STUDIES OF STRANGE THINGS.

I’m not especially knowledgeable about Lafcadio Hearn’s writings, but have read enough to recognize that Williamson’s pastiche of his style is remarkably successful. In tried-and-true Hearn fashion, the prose is straightforward and journalistic (Hearn started out as a newspaper reporter) in a determinedly archaic manner—although the story’s unflinching violence and sexual candor are most definitely 21st Century additions!

Interestingly enough, the book’s central flaw, if a flaw it even is, is identified by Chet Williamson himself in his introduction. He claims therein that the manuscript of NOICHI THE BLIND was discovered by his Japanese immigrant son Colin, who passed it on to Williamson. The latter reports that the first page “failed to excite me, seeming to be a very flat retelling of some Japanese folk tale”, but forges on because Colin assures him the tone is due to change dramatically. That more-or-less encapsulates my own experience reading this novella, which initially seemed like very little but grew steadily deeper and more compelling as it advanced. By the end I was convinced, and remain so, that it’s one of Williamson’s best-ever books.

It concerns Noichi, a simple woodcutter living “high in the hills” overlooking a Japanese town. A longtime confidante of the local animal population, Noichi’s life is one of peace and harmony—until one day a woman named Noriko shows up. Noriko is a brothel servant who’s on the run after accidentally murdering a passing samurai. Noichi takes Noriko in and inevitably falls in love with her. His animal friends, overjoyed at seeing their human friend so happy, help out Noriko by killing her pursuers, thus paving the way for everlasting happiness…or so it seems.

At around the halfway mark the story turns dark, and continues in that vein as Noriko falls ill and Noichi becomes determined to keep her alive at any cost. So desperate is Noichi to maintain his tranquility that he willfully blinds himself to quite a few unpleasant realities, such as the fact that his beloved wife dies…and that the body he continues to make love with is steadily decaying…and that the child Noriko eventually births is scarcely human.

The marvel of the tale is that despite its very up-to-date depictions of necrophilia, cannibalism and dismemberment, it still feels like an authentic Japanese folk tale of the type Lafcadio Hearn told so well. The afterward, credited to one Alan Drew, Ph.D. (a made-up personage; I checked), underlines this by outlining the story’s links to many of Hearn’s signature themes (while disputing the idea that Hearn actually wrote it).

THE STORY OF NOICHI THE BLIND also contains a stern message about the dangers of self-delusion, an admonition as relevant to our time as it is to the story’s late-19th Century setting. Not heeding it leads to Noichi’s unforgettably gruesome fate, in which the last two words of the title take on a very real, and disquieting, significance.