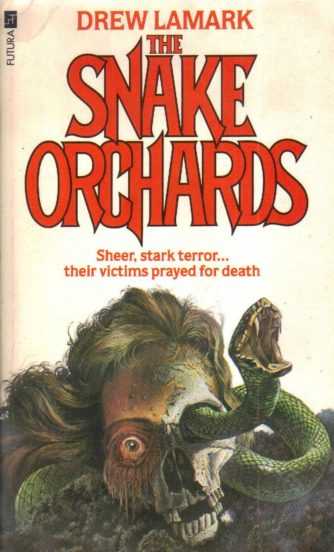

This relic from the “nasties” school of horror writing will always be important in my life due to the fact that back in the eighties it was one of the first grown-up horror novels I read. I was drawn, as I recall, by that eye-catching cover image, which remains quite striking (I would plug the artist, but none is credited). As for the text…

“Drew Lamark,” one of many pseudonyms of the prolific Andre Lavnay, delivered this late entry in the nasties cycle in 1982. By that point, of course, the cycle, which thrived in the late seventies, had died down considerably. This explains why this novel, and its mutant jellyfish themed follow-up THE MEDUSA HORROR, never got much traction.

That THE SNAKE ORCHARDS is somewhat lacking in gravitas is evinced by Futura’s misleadingly cryptic back cover plot description—“Sheer, stark terror as one man’s obsession becomes a stalk with silent death for a whole village of lost souls”—that all-but apologizes for the novel’s limitations by hinting at a depth that isn’t actually present. In truth the novel is an extremely simple-minded affair about a dour middle-aged snake enthusiast named Joffrin, employed as a caretaker on a swank British estate, who comes into contact with four highly venomous African snakes.

The fun begins when one of Joffrin’s snakes bites Colin, the adopted son of the estate’s owner, resulting in convulsions, hemorrhaging and death. Joffrin takes off, but not before stashing Colin’s corpse in an abandoned well along with the snakes, which Joffrin figures will drown. He figures wrong, as over the ensuing year the snakes actually thrive and reproduce, birthing hundreds of offspring. Around his time the estate is turned into a hotel with a full roster of guests, and a staff that includes Joffrin’s 19-year-old daughter Sadie. I think you can guess where all this is heading!

There are numerous snake attacks, but they’re not all they could be, marred by repetitive descriptions of snakes being mistaken for tree branches. It’s unfortunate, then, that those snake attacks are the book’s only real selling point. The characterizations are even more perfunctory than is the norm for this sort of fare; unsurprisingly, most of the characters are horny simpletons, with the only truly interesting personage, the morally questionable Joffrin, inexplicably spending much of the book’s second half offstage. One description, at least (the one depicted by the cover illustration), is memorably executed, but it doesn’t occur until near the end of the book, and is scant compensation for slogging through the preceding silliness.