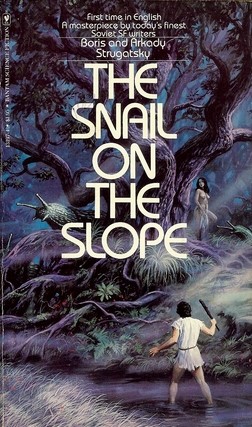

By BORIS & ARKADY STRUGATSKY (Bantam; 1966/80)

By BORIS & ARKADY STRUGATSKY (Bantam; 1966/80)

I’ll confess I didn’t think much of this, the most controversial—and, some claim, greatest—novel by Russia’s Boris and Arkady Strugatsky. The Strugatskys could be brilliant on occasion but also downright maddening, and this supposed “masterpiece,” I’m sorry to report, fits the latter category.

The Strugatskys could be brilliant on occasion but also downright maddening, and this supposed “masterpiece,” I’m sorry to report, fits the latter category.

The core concept is one the Strugatskys used often: a closed-off region where a skewed reality holds sway. Such was the idea behind ROADSIDE PICNIC, the authors’ most famous book (and also STALKER, the equally famous film adaptation by Andrei Tarkovsky), in which extraterrestrials on an Earth-bound stopover leave behind “The Zone,” a patch of land marked by strangeness and irrationality. THE SNAIL ON THE SLOPE contains a Zone-like enchanted forest, an unearthly landscape ruled by primitive magic.

The core concept is one the Strugatskys used often: a closed-off region where a skewed reality holds sway.

The story is two-fold, told from the points of view of Pepper, a petty functionary in a bureaucratic institution charged with studying and cataloguing the forest, and Kandid, who resides therein. Both men are outsiders in their communities, and harbor twin desires to venture beyond their respective environments—specifically, Pepper yearns for freedom from his tightly regimented existence (an idea that reportedly got the Strugatskys in a lot of trouble with Soviet authorities) while Kandid, who became stuck in the forest when a helicopter he was aboard crashed in the area, longs to return to the outside world.

The story is two-fold, told from the points of view of Pepper, a petty functionary in a bureaucratic institution charged with studying and cataloguing the forest, and Kandid, who resides therein. Both men are outsiders in their communities, and harbor twin desires to venture beyond their respective environments—specifically, Pepper yearns for freedom from his tightly regimented existence (an idea that reportedly got the Strugatskys in a lot of trouble with Soviet authorities) while Kandid, who became stuck in the forest when a helicopter he was aboard crashed in the area, longs to return to the outside world.

A strong set-up, to be sure, and many intriguing elements are incorporated, such as the details of the stifling Kafka-esque bureaucracy that governs Pepper’s place of employment and the bizarre day-to-day realities of life in the forest, which include flash floods, a perpetually warring populace and zombie-like beings called deadlings. The problem is that, either through a poor English translation (which among other sins renders a line of dialogue as “….”) or a too-culturally specific narrative (in his introduction author Darko Suvin admits the text is “somewhat puzzling,” with ambiguities that “cannot be deciphered”), the whole thing is quite cryptic and difficult to read. A lot of that difficulty, of course, arises from the authors’ full-bodied depiction of an irrational landscape, but the fact remains that this is a choppy and unsatisfying novel overall.