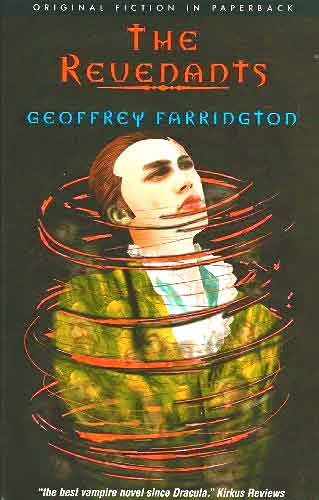

By GEOFFREY FARRINGTON (Dedalus; 1983/2001)

By GEOFFREY FARRINGTON (Dedalus; 1983/2001)

In his introduction to the 2001 edition of this criminally neglected novel Kim Newman calls it “a major achievement in its field.” He’s right. Even amid the current glut of vampire fiction (which unfortunately only appears to be growing steadily gluttier) Geoffrey Farrington’s THE REVENANTS remains a fresh, compelling and altogether brilliant take on vampire lore.

…this criminally neglected novel…

At once gritty and hallucinogenic, it’s told from the point of view of John Le Perrowne, a young man living in his family’s country estate in the late 19th Century. He’s haunted by a ghostly woman John identifies as his long dead great-great-great aunt Helena. He also suffers from some unexplained malady that, as I’m sure you’ve guessed, is in fact an early symptom of vampirism.

Precisely how and why John was vampirized isn’t revealed until late in the book.

Precisely how and why John was vampirized isn’t revealed until late in the book. Far more interesting are the details of his new state of being and how he adapts to it; this involves a literal journey into death, followed by a return to (eternal) life as a blood sucker, or, as these beings prefer to call themselves, revenant.

Helena teaches John how to live as a revenant, with an emphasis on morality and responsibility. She implores him to be stealthy in his hunting, and not to kill those whose blood he so ecstatically drinks. The episodes of blood drinking described here are redolent of the writings of Thomas de Quincy and other proponents of 19th Century drug literature in their sense of hallucinogenic delirium: “I was soaring, hurtling through immeasurable aeons and my body had no form but was mist on the winds of endless time, drifting to some nameless destination that might never be reached.”

Helena teaches John how to live as a revenant, with an emphasis on morality and responsibility.

On Helena’s advice they decamp for London, it being densely populated and so a more appropriate hunting locale than the country. Here John falls in with a mini-society of revenants who practice necromancy under the guidance of a far-off master vampire capable of transmitting his consciousness across great distances. These other revenants, unfortunately, don’t share Helena’s moral stance, and have no scruples about killing people.

The morality of his condition is something John has to face after he unwisely turns a young woman named Elizabeth into a revenant, and she goes on to become disturbingly bloodthirsty—the opposite of the more principled Helena. The crushing loneliness of a revenant’s existence is another problem confronting John, and an especially pressing one.

The book’s final third grows quite Lovecraftian, with John learning some dark truths about his family lineage and embarking on a search for the master vampire (this section also directly recalls the climactic passages of Michael Talbot’s THE DELICATE DEPENDENCY, published a year prior to the present novel). Yet the brooding menace of the earlier pages is fully sustained in a novel whose scope, ambition and imaginative richness are virtually without parallel.