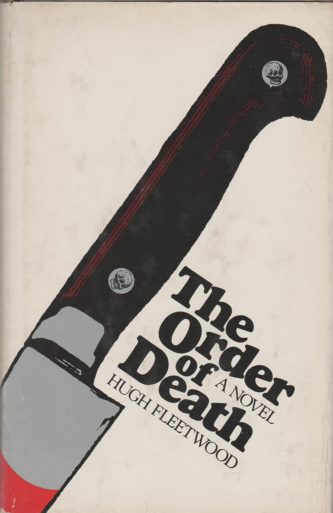

By HUGH FLEETWOOD (Simon & Schuster; 1976)

By HUGH FLEETWOOD (Simon & Schuster; 1976)

England’s Hugh Fleetwood is one of contemporary fiction’s best kept secrets, and THE ORDER OF DEATH is one of his most impressive novels. It’s also one of his all-around wildest efforts, encompassing police corruption, mass murder and psychological power play in a thoroughly idiosyncratic yet unerringly reader-friendly manner. It was adapted for the screen in the 1983 cult movie COPKILLER/CORRUPT, but attains its full power in textual form.

Anyone doubting Fleetwood’s talent need only read the opening pages of this novel, which outline the disturbed mindset of Fred O’Connor, a near-psychotically introverted NYC police detective. The smooth, confident prose attests to Fleetwood’s mastery, as does the fact that one is immediately engrossed in Fred’s exploits despite the fact that he’s a complete and utter loon.

Fred keeps a secret apartment where he frequently retires to indulge his mania for cleanliness and order. It’s his private haven from the world, which is why he’s decidedly nonplussed when a shifty young stranger begins asking for him, and eventually shows up at the place. This personage, one Leo Smith, promptly identifies himself as the cop killer that has been terrorizing the area. Fred reacts to this news in an odd (though not entirely uncharacteristic) manner: he beats up Smith and imprisons him in the apartment bathtub, forcing him to eat from a dog dish amid frequent bouts of brutality.

Research into the Smith’s life reveals that he’s a masochist who enjoys pain, which would seem to explain why he’s drawn to the mentally unstable Fred. Smith also has a habit of falsely confessing to crimes, suggesting that his latest admission is just another of his lies, and that Fred may actually be the cop killer—which given his tenuous psychological state and penchant for brutality doesn’t seem at all far-fetched.

The question of who the cop killer truly is goes unanswered until the final pages, with Fleetwood adroitly keeping us guessing throughout. As the book advances the dynamic between Fred and Smith becomes even more twisted (if that’s possible) than it was to begin with, with Smith assuming an increasingly dominant role over his captor. Adding to the madness is the presence of Fred’s nosy roommate Bob and the latter’s wife Lenore, with whom Fred has a decidedly complicated history.

Hugh Fleetwood pulls off this twisted tale with enormous ingenuity, spinning an energetic and surprising narrative whose psychological angle is disturbingly convincing. This is crime fiction at its most cutting and unpredictable, satisfying as a particularly gruesome psychological case study and also as, simply, a damn good read.