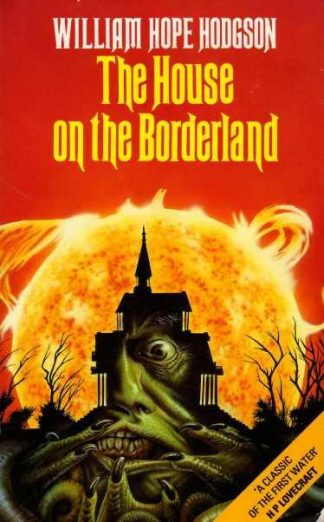

By WILLIAM HOPE HODGSON (Grafton; 1908/90)

By WILLIAM HOPE HODGSON (Grafton; 1908/90)

One of the true classics of the supernatural, this bizarre novel can almost be viewed as avant-garde sci-fi. The late William Hope Hodgson was a colleague of H.G. Wells, and THE HOUSE ON THE BORDERLAND is seen by some commentators as a psychedelic take on several key themes of THE TIME MACHINE. It can also be taken as a horrific predecessor to 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY, or simply an incomparably strange scare fest with a cosmic bent.

THE HOUSE ON THE BORDERLAND is seen by some commentators as a psychedelic take on several key themes of THE TIME MACHINE.

Like much of Hodgson’s fiction (notably the epic NIGHT LAND), it’s presented as a first person manuscript recovered by a third party. That manuscript is discovered in a set of ruins set atop a vast cavern. The circumstances of its retrieval, and those who affect it, are of little consequence. The contents of the manuscript itself form the bulk of the novel, a ceaseless stream of descriptive prose with no dialogue or subplots to break the spell.

Like much of Hodgson’s fiction (notably the epic NIGHT LAND), it’s presented as a first person manuscript recovered by a third party.

It’s the nightmarish reminiscence of “the Recluse,” an old man living in a sinister house with his loyal mutt Pepper and grown sister. The account begins in eye-opening fashion, with the Recluse visualizing himself leaving the Earth and alighting on a distant planet where a house very much like the one he currently resides in is situated upon a “Plain of Silence,” and attacked by a hideous swine monster.

The Recluse ends up back where he started, in the house with his dog and sister. Thus begins a pattern of sorts that sees the Recluse embarking on incomprehensibly vast sojourns through time and space, only to be abruptly thrust back to his point of entry.

Vicious swine creatures resembling the one seen in Plain of Silence are a constant in whatever reality the Recluse inhabits. One of the novel’s more effective passages has the Recluse exploring the cavernous area below his house—the Pit—and running smack into the swine things. Another powerful sequence occurs when the Recluse discovers a trap door from which issues distant laughter. Such intense sequences of old school horror don’t exactly jell with the hallucinatory flights of fancy, and that’s hardly the only jarring element.

…what ultimately resonates are the otherworldly episodes, in particular the final awe-inspiring journey through the cosmos.

On one of his travels the Recluse meets “her I love.” He doesn’t fill us in on who this individual is or how he came to love her, but claims her presence is the only reason he stays in the accursed house. What he neglects to tell us is why he moved into the abode in the first place. Could it be that he was somehow aware of the travails to come?

Of course here I’m attempting to make sense of Hodgson’s mysterious and inconclusive text, of which there are countless possible interpretations. The British novelist Iain Sinclair provides an extremely involved dissertation in an afterward to the 1990 Grafton paperback edition, positing among other things that the Recluse’s little-seen sister and his lover are one and the same. This would seem to make sense, although I’ve got my own ideas of what the Recluse, his sister, his lover and the swine creatures represent.

However you interpret this book, what ultimately resonates are the otherworldly episodes, in particular the final awe-inspiring journey through the cosmos. Here time inexplicably speeds up to the point that the Recluse finds himself plunged forward through countless light years, during which he witnesses the death of the sun and the Earth sucked into a vast green star. In his critical survey SUPERNATURAL HORROR IN LITERATURE H.P. Lovecraft claims this sequence represents something “almost unique.” I’d say it definitely represents a unique (no almost about it) and still-unmatched evocation of visionary horror.