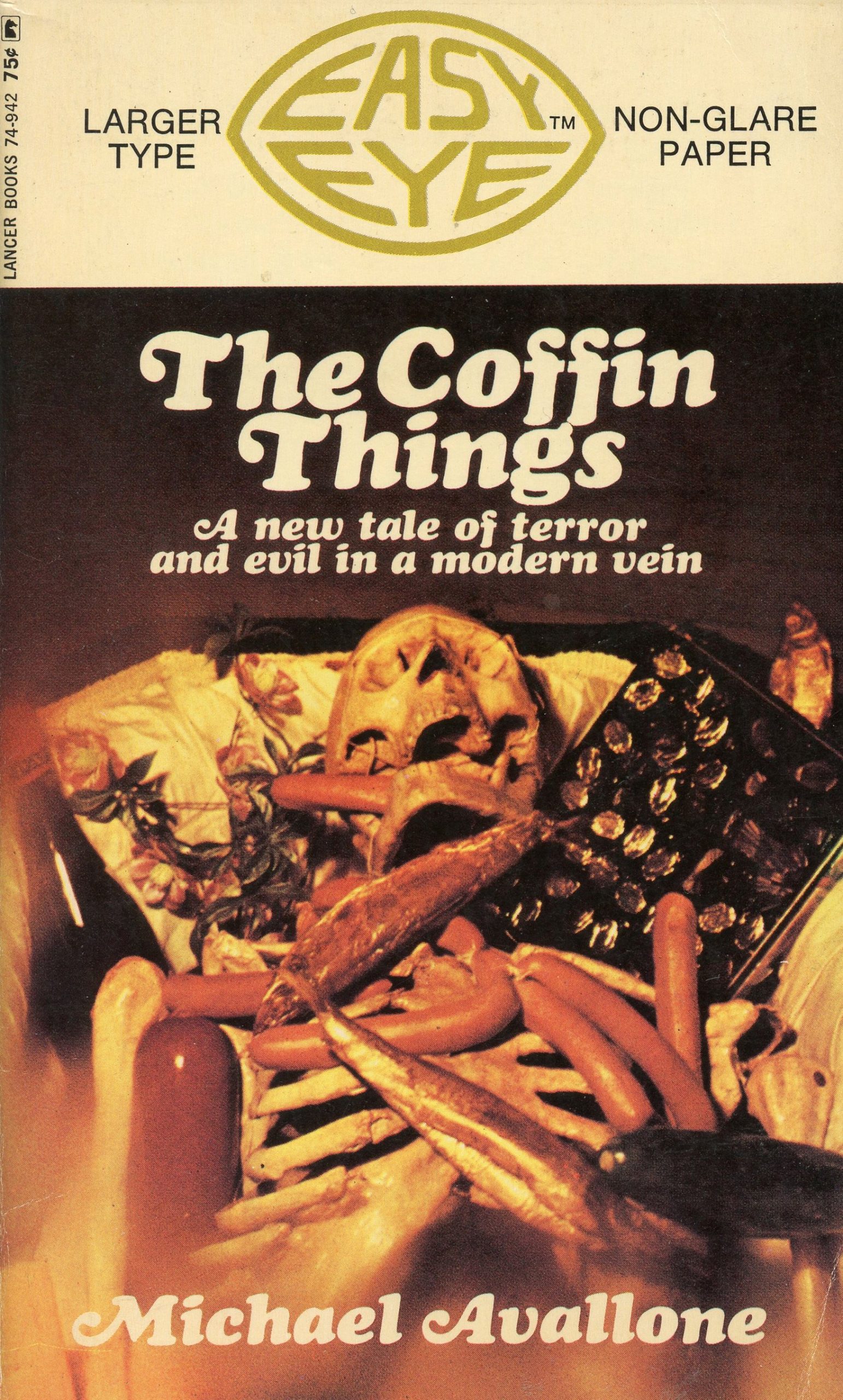

By MICHAEL AVALLONE (Lancer Books; 1968)

By MICHAEL AVALLONE (Lancer Books; 1968)

Michael Avallone (1924-99) was one of the most prolific hacks of the latter half of the Twentieth Century. His 200 plus novels include scads of movie novelizations (such as THE CANNONBALL RUN and FRIDAY THE 13: 3D), mysteries, secret agent potboilers, PARTRIDGE FAMILY tie-ins and a few horror novels, of which THE COFFIN THINGS is among the best known. Although by no means a best seller, it made enough of a splash in its day that it was optioned for film by Francois Truffaut.

That film was never made, which is a shame, as the novel is quite cinematic in its construction. Note the dedication to Robert Bloch, “who knows so well that DRACULA, FRANKENSTEIN and Brand X monsters aren’t the stuff that nightmares are made of.” Bloch, the author of the source novel for Alfred Hitchcock’s PSYCHO (among others), had no trouble creating movie-friendly horrors, and THE COFFIN THINGS is indeed very Blochian.

It involves Dr. Stewart Turner Garland, a mortician ensconced in Roseland, a wealthy upstate New York retirement community. Garland is quite skilled at his job, and indeed, it’s claimed that “The American Morticians Society of America consider the man a genius. He is to them what Michelangelo is to Rome.” This is despite an extremely checkered past that catches the attention of the local police department.

The novel opens with a discussion of Garland’s history by police officers investigating a suspicious death in Roseland. It’s the latest in a string of questionable deaths in the area, all of which involve individuals with connections to the horrific demise of Garland’s daughter. Thus we know immediately that Garland is a disturbed individual, and the subsequent chapters, in which he interacts (Norman Bates-like) with his apparently still-living offspring, underline that point.

Yes, this novel is quite dated. I say a more deliberate structure, in which Garland’s psychosis is gradually unveiled (as I believe Robert Bloch would have done) rather than revealed upfront, would have been more interesting, and I’m also at odds with the final chapter, in which the investigating officers wrap up the case with trite dialogue like “Garland was crazy and he accomplished all this. Ever think of what he could have done if he was all right in the head?”

The novel’s core of death-obsessed morbidity, however, remains potent and disturbing. THE AMERICAN WAY OF DEATH by Jessica Mitford, a 1963 book that was quite notorious in its day for exposing the awfulness of America’s funeral industry, is copiously referenced, and the final twist, involving Garland’s treatment of the corpses he handles, remains quite impacting (although it isn’t especially hard to predict).