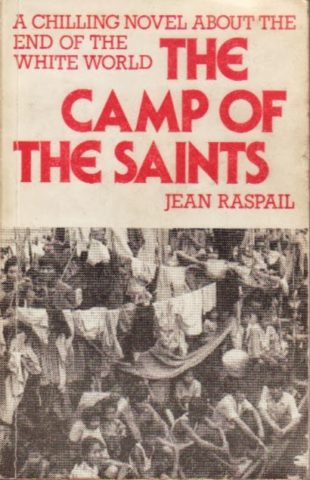

By JEAN RASPAIL (Social Contract Press; 1973/94)

This book, France’s answer to THE TURNER DIARIES, is the current bible of America’s alt-right movement. It’s a political screed disguised as a dystopian fantasy that gives vent to the near-hysterical fear so many white folks have of dark-skinned people penetrating their borders. Written back in the seventies, when concern about overpopulation was rampant in the first world, THE CAMP OF THE SAINTS deserves credit for bluntly stating a belief modern anti-immigrant pundits tend to play down: that third world immigrants, whose entry into France is likened by author Jean Raspail to a “river of sperm,” will dilute the purity of the white race. Racist? Most definitely, although the book’s narrator tries to get around that charge in a manner so many others have, by changing the definition of the word to suit his purposes: “What I always understood to be a simple expression of the races’ inability to get along together has become for my contemporaries—or most of them, I daresay—a war cry, a call to arms…”

It begins with an elderly literature professor bemoaning the fact that a horde of Indian refugees have been breached “the sacred portals of the Western World.” He’s joined by a carefree hippie who proclaims that “I sponged off society while it was alive, so now that it’s dead, I’m going to pick its bones” (an example of how the characters in these pages all speak in political slogans rather than conversational speech). The old man shoots the hippie, after which he finds himself “more exquisitely at peace than he ever remembered being.” That about sums up the level of discourse presented in THE CAMP OF THE SAINTS.

Much of the rest of the book consists of an extended flashback that details how Catholics, unions and left-wingers everywhere (the Jews, for once, aren’t implicated) conspired to convince the people of France that letting in the Indian refugees was a good idea. Raspail isn’t at all shy about informing us, in lengthy tirades that periodically interrupt the narrative, that this course of action is wrong. To help make his point Raspail includes endless descriptions of the sordidness and ugliness of the refugees, a bunch of malformed freaks driven by blind hatred and xenophobia (yes, the author, evidently foreseeing the primary criticisms that would be levelled at him, uses those very words to describe his antagonists) who subside on their own feces and are led by a figure identified only as “turd eater.”

A fair amount of suspense is built up as the fleet carrying the horde makes its way toward France. During this time several white men along for the ride are killed by the horde, and another driven mad by the bad behavior he witnesses. Back in France the fleet becomes a symbol of hope for downtrodden citizens, while the French president, being a rich white man, and so one of the few who understands the apparent severity of the horde’s intrusion into the white world (Raspail hates the poor nearly much as he does nonwhite people), orders the military to open fire upon the fleet as it docks in France. Needless to say, this doesn’t go well, and events take their inevitable course.

All of this would be easy to dismiss were it not for the fact that this book is held in such high regard by so many powerful people (it’s reportedly a favorite of ex-Trump advisor Steve Bannon). Much praise has been heaped upon its stately and “poetic” prose, and Jean Raspail does indeed have a way with words (even if the English translation by Norman Shapiro doesn’t always render them in ideal fashion). That may be what has led so many otherwise intelligent people to believe that this silly and reactionary screed actually has something worthwhile to say. Quite simply: it doesn’t.