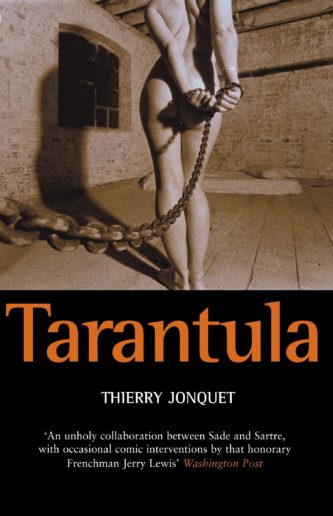

By THIERRY JONQUET (Serpent’s Tale; 1999/2005)

By THIERRY JONQUET (Serpent’s Tale; 1999/2005)

TARANTULA is a we have a fascinating hybrid, a suitably hard boiled noir thriller with a freaky psychosexual edge. Short, sharp and shocking, it’s a product of the late French crime specialist Thierry Jonquet, who here crafted a thoroughly unique piece of work.

… a thoroughly unique piece of work.

These days TARANTULA is known primarily as the source material for Pedro Almodovar’s 2011 flick THE SKIN I LIVE IN, but the novel deserves to be considered as the standalone oddity it is (for starters, it’s far superior to the film). It should also be identified by its original French title MYGALE (as City Lights’ initial English version rightfully was) rather than its English translation TARANTULA, for reasons that will become apparent in the next chapter.

These days TARANTULA is known primarily as the source material for Pedro Almodovar’s 2011 flick THE SKIN I LIVE IN, but the novel deserves to be considered as the standalone oddity it is (for starters, it’s far superior to the film).

See full review of movie THE SKIN I LIVE IN.

The book begins in teasingly elusive fashion, juxtaposing three seemingly unrelated narrative strands. In one a wealthy surgeon callously abuses his partner Eve, who he drags with him to visit a young relative in a mental hospital, and who he further degrades by forcing her to perform sex acts with strangers. In another strand a petty criminal is on the lamb after murdering a policeman, while in the third and most impacting strand a man is abducted and imprisoned in a dark chamber, where he suffers all manner of abuse at the hands of a shadowy stranger he comes to know as Mygale. As noted above, mygale means tarantula, but it’s also a woman’s name, which is appropriate for the odd mixture of horror and tenderness with which the prisoner comes to regard his captor.

…a novel that reads like a Jim Thompson potboiler reimagined by the Marquis de Sade.

The spider reference is also appropriate to the web-like construction of the narrative, with various strands that are gradually connected until the whole thing coalesces into a satisfyingly multilayered whole. I won’t reveal precisely how the narrative plays out, though be advised that some of the developments are deeply and thoroughly perverse. The writing is appropriately sharp and concentrated (although French speaking readers claim the English translation fails to capture the spirit of the original text), adding to the intrigue of a novel that reads like a Jim Thompson potboiler reimagined by the Marquis de Sade.