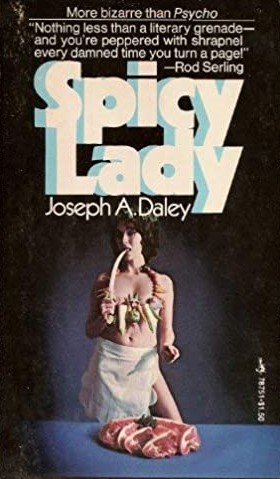

By JOSEPH A. DALEY (Pocket; 1973/74)

By JOSEPH A. DALEY (Pocket; 1973/74)

The term “product of its time” could have been coined to describe this novel. Judging by the critical blurbs on its mass market edition (“Nothing less than a literary hand grenade”), SPICY LADY, a would-be psychothriller, was evidently quite the shocker when it first appeared in 1973. Now it feels pretty tired, pivoting as it does on a climactic revelation that’s not at all difficult to foresee.

The title refers to a TV cooking show. Its producer, a fellow named Jack Shaw who thinks he’s seen it all, believes he’s found his ideal hostess in the form of Wanda Fleischer, a buxom Holocaust survivor who happens to be close friends with Jack’s wife. His instincts prove to be on point, as Wanda, an ace cook with a penchant for witty banter and salty wisecracks, is a massive hit with viewers.

Behind the scenes, however, not all is well. Wanda exhibits an unpredictable temper and exerts a hold over Jack’s wife that grows increasingly sinister. Two men in Wanda’s orbit disappear mysteriously, including her nosy building manager Bernie, and questions are raised about the true nature of Wanda’s Holocaust experiences and the sources of the meat she dishes up so abundantly—particularly following Bernie’s disappearance.

There’s no point going into the explanations for all this, as you’ve most likely figured out the major ones. Yet author Joseph A. Daley takes up much of the book with Jack’s investigation into Bernie’s disappearance, with the Shocking Revelations about Wanda’s true nature unveiled in the final twenty pages. Once again: no points for guessing what they are.

Another problem is with the writing. In the manner of many show business novels, this one is filled with insider detail that tends to overwhelm the narrative–which taken by itself is perilously thin. I also question just how knowledgeable Mr. Daley was about show business, as his characters are of the uber-cynical, fast-talking type that far too many authors think constitute show biz folk (when in reality such people tend to be meek and insecure).

One aspect of this book that can be viewed as a positive or a negative, depending on the reader’s point of view, is its very period specific language and milieu. It’s quite “with-it” in early 1970s terms, with references to Earl Wilson, DesiLu, Herman’s Hermits, etc., not things you can expect to hear about much today, but which were quite topical in 1973. So too this novel, whose forgotten relic status is fully deserved.