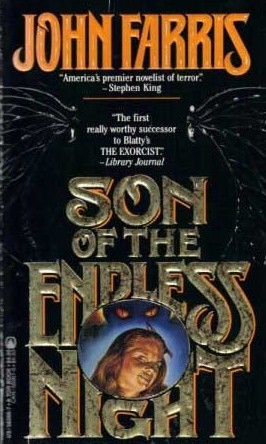

Horror epics were something of a novelty back in 1984. One of the rare examples of such was SON OF THE ENDLESS NIGHT by John Farris, a 500-plus page account of demonic possession with a twist: here the possessed individual is actually tried for his crimes in a court of law—a court located, interestingly enough, in Vermont, not far from the from the site of the original American witch trials in Salem, Massachusetts.

The sprawling narrative is divided into three distinct portions, with part one, describing the events that inspire the trial, being the most compelling. Lasting a little over a hundred pages, it focuses on Richard Devon, a concerned man lured to a burned-out wing of a secluded hotel by a spectral girl. These passages are as haunting and foreboding as anyone could desire, while the following ones, detailing a spectral banquet that turns into a deeply perverted incantation, radiate a palpable sense of evil. Following this the now-possessed Rich beats his wife to death with a car jack in the first and most impacting of quite a few gory set pieces.

In part two Rich’s virtuous pro wrestler brother Conor takes the lead. He and we learn that Rich is possessed by none other than Zarach’ Bal-Tagh, the brother of Lucifer, who’s looking to make trouble for mankind in the final days of the 20th Century. Among Zarach’s outrages are some gravity-defying gymnastics performed in his host body’s jail cell and a succession of gory killings, the most memorable of which involves a cop literally sucked into a toilet. Zarach also tries to snatch Conor’s daughter, but the attempt is foiled in a wild, psychedelic car chase.

It isn’t until part three that the aforementioned trial finally gets under way. It involves a defense attorney seeking the first-ever verdict of Not Guilty by Reason of Demonic Possession. Arrayed against him are a world famous prosecutor and of course Zarach, who continues his supernatural pyrotechnics in the courtroom. It’s up to the harried protagonists, together with representatives of an obscure religious sect that calls itself the Sundial Community, to resist Zarach’s shenanigans and obtain the desired verdict.

This novel is a mixed bag, and not only due to the fact that its epic canvas is no longer as unprecedented as it once seemed. The energy, atmosphere and fully rounded characterizations are a testament to John Farris’ novelistic mastery, but the highly uneven three part narrative has the feel of a short story collection rather than a unified whole. The many over-the-top horrific set-pieces are another negative; at best they add a demented energy to the story (the abovementioned toilet sucking in particular), while at their worst they feel like crummy cast-offs from THE OMEN, seemingly written with an eye toward a potential movie sale. Subtlety was clearly not a characteristic of Zarach, nor the overall novel.