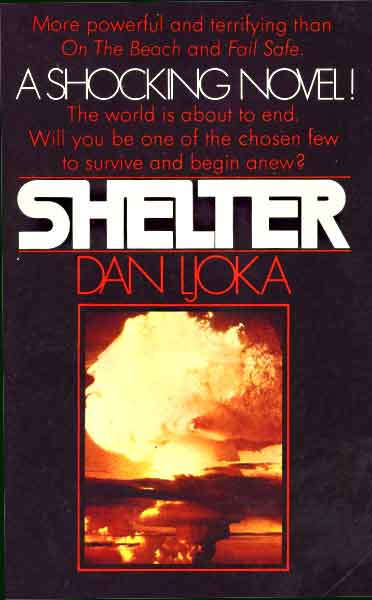

By DAN LJOKA (Manor Books; 1973)

By DAN LJOKA (Manor Books; 1973)

A paperback original that can be viewed as the trashy down-market inverse of ON THE BEACH. As in that classic, the subject of SHELTER is nuclear war, about which author Dan Ljoka seems legitimately knowledgeable and concerned. He’s also careful to keep his text short and sensation packed.

…short and sensation packed.

It begins with the Earth being nuked. As the nuking occurs Paul, a Washington, DC based astronomer, is giving twenty members of a women’s group a tour of a fallout shelter underneath the observatory where he works. Thus he and the gals find themselves trapped in the shelter for the foreseeable future; luckily the place is well stocked and in working order.

It begins with the Earth being nuked.

From there the novel clumsily switches its vantage point to New Zealand, one of the few places in the world the nuclear bombs haven’t hit. Toxic radiation, however, is heading toward the country, forcing its Prime Minister to come up with a lottery to determine who will get to reside in the nation’s fallout shelters for the next two years. This leads to rioting and the complete destruction of all but one of the shelters—the very one, it so happens, in which the Prime Minister is set to reside. This forces him to do some quick planning, and results in a morally questionable act that involves leaving infant children splayed out on the ground to (hopefully) stop the mobs.

Cut back to Paul and the women in the Washington, DC shelter. Relations therein are strained from the start, and grow even more so when a psychotic lesbian asserts her will, chaining up Paul and turning him into a one-man stud farm for the ladies, so as to have a brood with which to rule the world.

The writing, in keeping with the novel’s early seventies paperback original status, is a bit crude. The author has a bad habit of suddenly switching viewpoints, and his dialogue, of which there’s a great deal, tends toward the wooden and expository (with the evil lesbian broadcasting her true nature by speaking in clipped, slang-ridden sentences dotted with “ain’t”). Mr. Ljoka’s storytelling instincts, at least, are solid: the narrative may be clumsy in its juxtaposition of THREADS-like realism and gross-out sensation (as when Paul is forced to dismember a woman’s corpse so it can be disposed of in the shelter toilet), but it’s also appropriately relentless. That’s particularly true of the final pages, which close things out on a somber note that proclaims the allotted two years in a fallout shelter will not be long enough for the above-ground radiation to dissipate, and that, no matter how much we might try to hide from it, the effects of nuclear war will kill us all sooner or later.