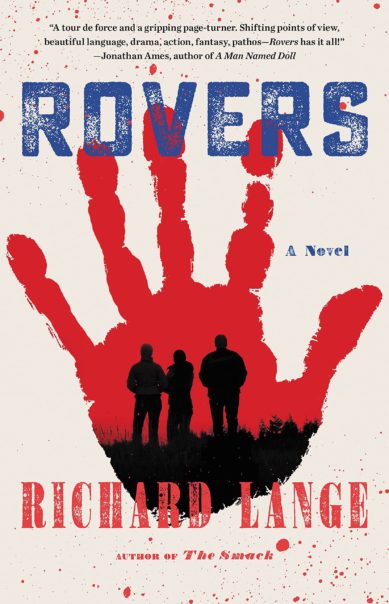

By RICHARD LANGE (Mulholland Books; 2021)

By RICHARD LANGE (Mulholland Books; 2021)

A testament to the continuing influence of Kathryn Bigelow’s NEAR DARK (1987) on contemporary vampire media. ROVERS is very much like NEAR DARK in conception and execution, tracking a grungy band of nomadic bloodsuckers through a desert landscape in an action-oriented odyssey that’s equal parts Bram Stoker and Sam Peckinpah.

… equal parts Bram Stoker and Sam Peckinpah.

The title refers to rootless vampires living in the year 1976. These Rovers can eat and drink like the rest of us but have to imbibe human blood every few weeks in order to keep from decaying—although if the blood is that of an infant they can last months without having to feed.

Jesse is a rover haunted by the killing of his beloved Claudine 70 years earlier. He’s now on “the roam” with his mentally impaired brother Edgar, who’s “fifty years old outside and ten inside his head.” When Jesse meets a Native American bartender named Johona who happens to be the spitting image of Claudine it would seem he’s found an antidote to the crushing loneliness that is his lot. But he’s gravely underestimated Edgar, who has a “Little Devil” inside that makes him do things that are questionable even by Rover standards.

Sanders is a pious non-vampirized man who’s searching for the murderer of his young son Benny, unaware that the boy was killed by a vampire—although Sanders is not destined to stay in that unaware state for very long. Inevitably the paths of Jesse and Edgar, which commence in Arizona, cross with that of Sanders, and also a ruthless vampire biker gang known as the Fiends, in an odyssey that concludes, quite bloodily, in Las Vegas.

The orgasmic blurbs bestowed upon this novel—Joe Hill calls it a “pulp masterpiece of American horror” while Alma Katsu dubbed it “achingly beautiful” and even Stephen King has joined in the praise—are a bit overwrought, but it is in fact pretty damn good. The prose is appropriately tough and hard-bitten, the violence (in keeping with the desolate 1970s setting) quite relentless and the characters much better drawn than those of most vampire fiction. There also exist passages of real tenderness and pathos, although they are, as you might guess, few and far between.

…Joe Hill calls it a “pulp masterpiece of American horror” while Alma Katsu dubbed it “achingly beautiful” and even Stephen King has joined in the praise,,,

On the downside are some needlessly distracting stylistic choices. Certain chapters are related in the first person—usually from the POVs of Sanders, in form of letters to his wife, and Edgar—and others in the third, while the timeline tends to loop around itself to retell events from different points of view, the reasons for which are never made apparent.

I also have an issue with the conclusion, which is neither “happy” nor unhappy. What it definitely isn’t is entirely satisfying. It’s possible, in the curiously unsettled state in which he leaves many of his characters, that the author was anticipating a sequel. Fine, but until it arrives we’re stuck with a book that ends quite awkwardly.