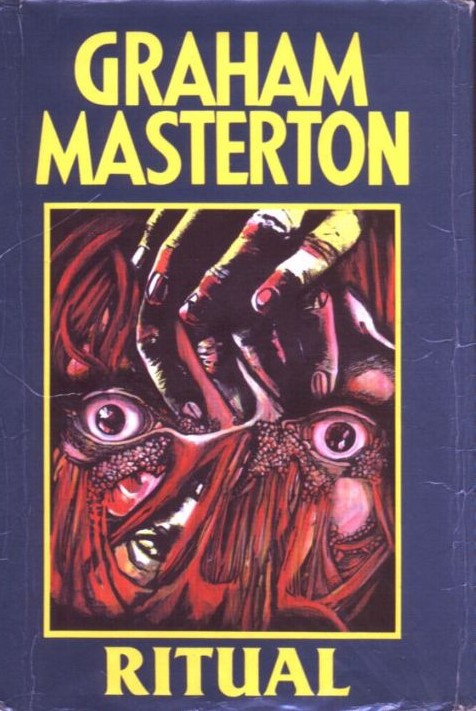

By GRAHAM MASTERTON (Severn House; 1988)

By GRAHAM MASTERTON (Severn House; 1988)

There are some ingeniously nasty elements in this 1988 horrorfest, yet also some misconceived ones, all packed into a vastly overblown framework. RITUAL (known as FEAST in the US) is, in short, a Graham Masterton novel, with all the plusses (crisp detail-oriented prose, a lively and imaginative narrative drive) and minuses (an overlong and uneven framework) that portends.

The subject is a highly exclusive restaurant called Le Reposoir, contained in a forbidding mansion. It’s situated in Allen’s Corner, a small Connecticut town where no children are to be found and everyone behaves in an apprehensive and suspicious manner. Upon learning of the existence of Le Reposoir the restaurant inspector Charlie McLean is intrigued and, even though it’s not on his itinerary, grows determined to sample their cuisine.

The author’s research into the intricacies of restaurant inspection is impressive, and livens up a book that in its first half is quite compelling (the repetitive dream passages, in which we’re let in on Charlie’s subconscious reactions to what he’s experiencing, aside). It’s in RITUAL’s first half that we learn Charlie’s traveling companion, his estranged fifteen-year-old son Martin, is growing increasingly preoccupied.

Any number of parental fears are mined here, with Martin drawn away from Charlie and bolting the hotel room he shares with his father in favor of Le Reposoir, where it seems he’s being groomed to become the main course in an upcoming banquet. Yes, the depraved folks who run Le Reposoir are cannibals, and disciples of the Celestines, a religious sect that takes the act of consuming the flesh and blood of Christ quite literally—although their activities are tempered in the eyes of the law by the fact that these freaks encourage their adherents to devour their own flesh (against which there’s apparently no law on the books) and leave their fellows to nosh on the leftovers. They particularly favor the flesh of children, which explains why there are no kids to be found in Allen’s Corner, and why the Celestines have taken such a keen interest in Martin.

Charlie’s attempts at rescuing his son prove quite arduous, as the police and even the United States government sanction the activities of these weirdoes. He ends up gaining a partner in the form of Robyn, a woman reporter with whom he travels to New Orleans (and, needless to add, has sex), where the Celestines happen to be centered.

It’s at this point, unfortunately, that Masterton loses control. A passage where Charlie attempts to join the Celestines, and in doing so submits to a truly horrific initiation ritual, is stunningly grotesque and audacious, but much of the rest of the New Orleans set portions simply don’t work. That’s especially true of the climax, in which the book’s religious overtones are made quite overt; those readers who, like me, were put off by the last-minute cameo by the Big G in King’s THE STAND will be even more nonplussed by THE RITUAL’s divine intervention, which is out of place and plain dumb.