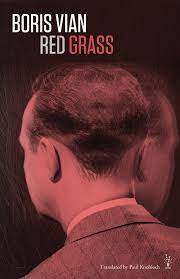

By BORIS VIAN (TamTam Books; 2013)

By BORIS VIAN (TamTam Books; 2013)

A novel as puzzling and bizarre as nearly any I’ve read, filled with enigmas I’m told will come clear on subsequent readings. The author was France’s late Boris Vian, who in better-known works like FROTH ON THE DAYDREAM, HEARTSNATCHER and the notorious I SPIT ON YOUR GRAVES demonstrated a real facility for shock, surrealism and the unexpected. RED GRASS, which was initially published in 1950 but only found fame upon being posthumously reprinted, is one of his more atypical novels, a death-obsessed head-scratcher with a science fictional premise. This, the first and thus far only English translation, was accomplished by Paul Knobloch.

The language is odd, and oddly rhythmic, with an unforced nonchalance that imparts a surreal, and vaguely satiric, tone. The setting is some future era, or perhaps an alternate universe present, where the grass, as the title indicates, is blood red (seeming, as one character observes, “sinister”) and people have odd hobbies with names like “rednecking” and “thigh climber,” and don’t evince any qualms about the presence of a talking dog, known as Senator Dupont, among them. Another odd element is “the machine,” a walk-in contraption built by the protagonist Wolf and his mechanic pal Saphir Lazuli. ‘

Wolf intends to utilize the machine, whose interior is often likened to a cage (and which appears to operate much like H.G. Welles’ time machine), to erase unwanted childhood memories. Yet when he uses it he’s confronted with, first, an old man who subjects him to questions about his past in what seems suspiciously like psychoanalysis (a practice Vian reportedly despised) and, second, a Kafkaesque office setting in which Wolf is subjected to more psychological probing. On his final usage he’s interrogated by a pair of old ladies on a beach.

Vian also devotes many a page to Wolf and Lazuli’s deteriorating relationships with their wives, which apparently mirrored Vian’s own marital crisis, which was ongoing when he wrote this novel. Then there are the unidentified figures who torment Lazuli, figures who have a tendency to suddenly appear and disappear without warning; they play a large part in the bloody final pages, where these personages are all revealed to look exactly like Lazuli himself. If any reason is given for this occurrance I missed what it was, although by that point surrealism had so overpowered the narrative that any sense of logic had long since evaporated.

The introduction by Marc Lapprand, a French professor and expert on all things Vian, doesn’t appear to comprehend the book much better than I did (Lapprand expends more ink on the various alternate titles Vian had for the manuscript and its not-very-invigorating publishing history than he does on its story and characters). Furthermore, Lapprand suggests it was never properly fleshed out: “It looks as though THE RED GRASS was only the premise of a complete analysis,” which is exactly how it reads.