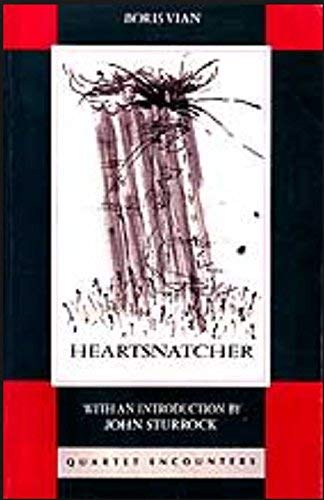

By BORIS VIAN (Quartet Books; 1953/68/89)

By BORIS VIAN (Quartet Books; 1953/68/89)

France’s Boris Vian is something of an acquired taste. He specialized in highly fanciful, surreal narratives (such as FROTH ON THE DAYDREAM and RED GRASS) related in unnervingly nonchalant prose. That combination is an odd and at times off-putting one, particularly in English.

Thankfully Stanley Chapman, who did the English translation of HEARTSNATCHER, Vian’s last novel, did a credible job. His is a “free” translation, which was a necessity given the source; as the London Review of Books reviewer John Sturrock states in his introduction, “you have to try and do a Vian in English, to make up words, to invent. Mr. Chapman has done a supremely good Vian here.”

“You have to try and do a Vian in English, to make up words, to invent. Mr. Chapman has done a supremely good Vian here.”

This was apparently one of Vian’s deepest and most personal novels, a symbolic odyssey with some profoundly disturbing undertones. The protagonist is Timortis, a psychiatrist so lacking in character and individuality that he remembers nothing of his past. He’s devoted his life to observing the behavior of others, in this case the inhabitants of a rural village overrun with odd vegetation and ruled by an even odder neo-pagan religion.

HEARTSNATCHER’S heart (so to speak) is Clementine, a young woman who gives birth to triplets. She’s initially ambivalent about the kids, and drives her husband away, blaming him for the pain of the delivery. But she grows increasingly attached to her three boys and is beset by thoughts of unspeakable calamities befalling them (“Noel’s flat on his back. There was nobody to see him fall and now there’s an invisible fracture hidden under his fine golden hair…And then, suddenly, his skull splits wide open, the fracture has gone all the way round, and off comes the top of his head like a lid”). Unaware that the boys have learned to fly by eating blue slugs, Clementine takes ever more drastic measures to keep them safe, including cutting down every tree in the area, constructing an invisible wall (so the kids won’t know it’s there) and, finally, the procurement of golden cages in which the boys are locked.

“Noel’s flat on his back. There was nobody to see him fall and now there’s an invisible fracture hidden under his fine golden hair…And then, suddenly, his skull splits wide open, the fracture has gone all the way round, and off comes the top of his head like a lid.”

Timortis, meanwhile, becomes increasingly involved in the affairs of Clementine, her children and the surrounding village. This is in defiance of his policy of non-engagement in human affairs, and his ultimate fate—not to spoil anything, but he ends up stuck in this bizarre place and made an integral part of its rituals—is a most ironic and appropriate one.

As a surreal fantasy HEARTSNATCHER only works sporadically. Its depiction of abuse through overattentive parenting is far more impacting precisely because, despite the surreality, it feels so real. This results in a novel at war with itself, presenting a vision at once deeply fantastic and all-too true-to-life. In such a thematic tug-of-war only one portion emerges victorious, and it ain’t the surreal one.