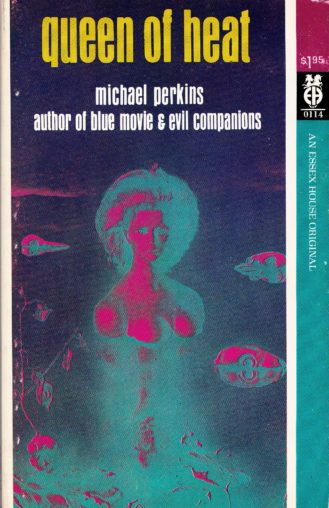

By MICHAEL PERKINS (Essex House; 1968)

By MICHAEL PERKINS (Essex House; 1968)

A stellar entry in the esteemed late-1960s Essex House line of erotica, written by one of Essex’s most talented and prolific contributors. It followed Michael Perkins’s better-known EVIL COMPANIONS, which was notorious for its unrelenting depictions of death and perversion in a counterculture setting. QUEEN OF HEAT is similarly oriented, with its biggest shortcoming being that, simply, it isn’t as strong as its predecessor. Taken purely on its own terms, however, QUEEN OF HEAT is a powerful evocation of the dark extremes of eroticism.

The novel is narrated by the inquisitive New Yorker Jack, who at age nineteen meets Alice, a much older and more experienced woman. She seduces Jack at an upscale party (apparently “the first I had been to where cokes and potato chips weren’t served, but champagne with strawberries”), which sets him off on a frenzied quest for erotic gratification via a succession of young women. These encounters are from the start decidedly twisted and perverse, with Jack freely employing rape, intimidation and physical abuse upon his conquests (it’s not insignificant that he likens one of his relationships to cannibalism: “either she would eat me, or I’d eat her”).

Inevitably murder comes into play, in the form of a young man pushed down an elevator shaft. Further killings are imminent as Jack’s eroto-mania intensifies, and culminates in a fateful cruise, arranged by Alice, that deposits him in a Haitian village. There the naughtiness reaches its apex in a haunted atmosphere suffused with black magic.

The somewhat enigmatic concluding passages can be read as a happy ending or a bleak one, depending on one’s point of view. It’s here that the story’s mythological underpinnings—with the climactic Caribbean cruise, for instance, being an obvious crossing of the River Styx—are laid bare, and what may have initially seemed like a random succession of perverse couplings is revealed as a sustained initiatory rite brought about by a calculating Medusa figure. Jack’s odyssey is far from warm and pleasant, although (as Philip Jose Farmer makes clear in his afterward, which drags Hegel and Nietzsche into its analysis) it is quite intelligently rendered and even educational, and light years removed from standard stroke book fodder.