By PETER STRAUB (Cemetery Dance; 1994/2010)

By PETER STRAUB (Cemetery Dance; 1994/2010)

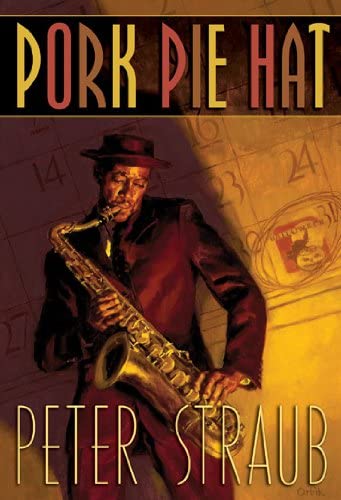

A novella that united two of the late Peter Straub’s major passions: jazz and horror, contained in an engaging Halloween tale. Initially published as part of the 1994 anthology MURDER FOR HALLOWEEN, PORK PIE HAT made it to standalone book format in 2010. Containing five black-and-white illustrations by Jill Bauman, the book runs 148 large-printed pages, and offers (further) proof that Straub did his best work in novella form.

Containing five black-and-white illustrations by Jill Bauman, the book runs 148 large-printed pages, and offers (further) proof that Straub did his best work in novella form.

Featured are the time tripping narrative perturbations that typify Straub’s post-GHOST STORY fiction, with a story related by two distinct voices, and set in just as many settings and time periods. Also present are the author’s strong grasp of characterization and not-inconsiderable descriptive power.

The Caucasian narrator is a young NYC based jazz aficionado, and the situation a meeting with the African American Pork Pie Hat, a legendary jazz musician the narrator assumed was long dead. The very-much-alive Hat is found playing in an East Village jazz club, where the narrator works up the nerve to ask his idol, about whom little documentation exists, for an interview. That interview tales place in a Manhattan hotel on Halloween night, an opportune date because Hat’s rambles involve an extended childhood memory that also occurred on All Hallows Eve.

Featured are the time tripping narrative perturbations that typify Straub’s post-GHOST STORY fiction, with a story related by two distinct voices, and set in just as many settings and time periods. Also present are the author’s strong grasp of characterization and not-inconsiderable descriptive power.

Hat’s recollection, which the narrator admittedly reframes in his own words (as “if I tried to imitate his grammar, I’d sound racist and he would sound stupid”), takes place in Hat’s hometown of Woodland, Mississippi. It was there that Hat, together with a pal nicknamed Dee (short for “Demon”), entered a rough area of town known as the Backs to raise some hell—because “You were supposed to raise Hell, on Halloween.” Costumed in white sheets, Hat and Dee witness a (seeming) murder, rendered all the more shocking by the presence of a white man (“Once a white man walked out the door, it was like raising the stakes in a poker game”).

We never learn the outcome of what happened all those years ago in the Backs, or if anything of note truly happened at all. The drug-addled Hat, as is made clear early on, is a less-than-reliable narrator, and quite possibly insane.

He is, however, extremely well characterized, as is the jazz milieu in which he resides. Plus his ultimate message is a pertinent, and extremely characteristic, one: “Most people will tell you growing up means you stop believing in Halloween things—I’m telling you the reverse. You start to grow up when you understand that the stuff that scares you is part of the air you breathe.”