By MAURICE SANDOZ (Doubleday; 1950)

By MAURICE SANDOZ (Doubleday; 1950)

A macabre anthology from France’s Maurice Sandoz that in the retinue of English language Sandoz publications (which include THE MAZE, FANTASTIC MEMORIES and THE HOUSE WITHOUT WINDOWS) ranks near the bottom. Like many of his books, ON THE VERGE purports to be an actual memoir, with the subject being one that’s fascinated horror scribes forever: madness, as elucidated by a preface in which it’s explained that Sandoz spoke with numerous insane asylum patients to explore “that most puzzling of all labyrinths, so well typified by the convolutions of the human brain.”

Like many of his books, ON THE VERGE purports to be an actual memoir…

The first story is “The Tsantsa,” about a Brazil based Frenchman who becomes infatuated with a woman who desires above all else a Tsantsa, or severed head. The protagonist goes about procuring the desired object, only to find his own head shrinking (or seeming to). The explanation for this happening concludes the story.

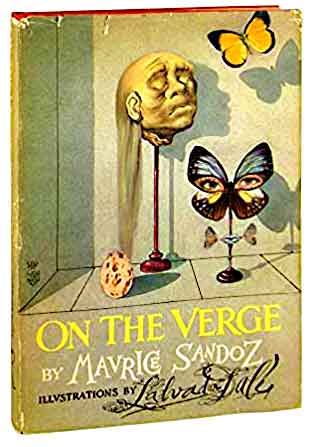

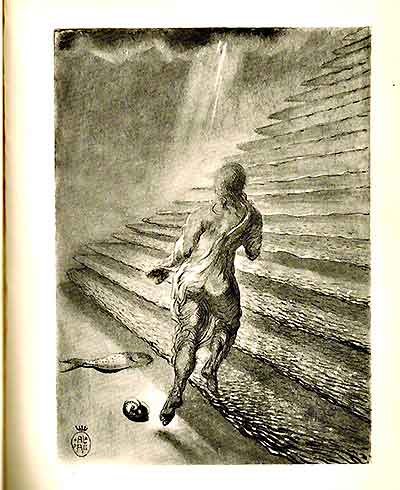

This book is, like many of Maurice Sandoz’s others, known for specially commissioned full-page illustrations by Salvador Dali.

In “Mr. Rabbi,” the weakest of ON THE VERGE’s contents, the narrator interviews a mental patient claiming to be Jesus Christ. The latter’s descriptions are apparently so convincing his interrogator comes to believe them, although the rest of us may not be too swayed comments like “A tree which bears no fruit at the right season is a tree well-nigh dead.”

In “Mr. Rabbi,” the weakest of ON THE VERGE’s contents, the narrator interviews a mental patient claiming to be Jesus Christ. The latter’s descriptions are apparently so convincing his interrogator comes to believe them, although the rest of us may not be too swayed comments like “A tree which bears no fruit at the right season is a tree well-nigh dead.”

What follows is the best of these tales, an odd and unnerving account called “The Trap.” Its subject is a British officer discussing his WWII exploits in North Africa, where, he claims, he was dispatched to track down a colleague who went missing in the Oasis of Nefta. What the officer discovers is an inviting looking swimming pool in which, in a most unwise move, he decides to take a swim. He quickly finds himself in an extremely odd and unexpected predicament as it becomes impossible to get out.

…an odd and unnerving account called “The Trap.”

The final story is the one that gives the book its title. It once again has the narrator getting talked into believing the rantings of a madman, albeit one who purports to be acting in concert with the rest of the world, which, he claims, was created and run by crazy people. As in “Mr. Rabbi,” the arguments employed in defense of this hypothesis are unconvincing, but they apparently seduce the narrator into believing the interviewee isn’t actually mad, which turns out to be a big mistake.

This book is, like many of Maurice Sandoz’s others, known for specially commissioned full-page illustrations by Salvador Dali. Seven, to be exact, the first of which (which adorns the cover and title page) is presented in full color, and the rest in extremely sketchy black and white. Those illustrations are striking, although I’m not sure they add a whole lot to the text, and nor do they constitute the “collaboration” promised by the dust jacket, which further touts “the spectacle of one highly imaginative artist interpreting the work of another.” Not quite!