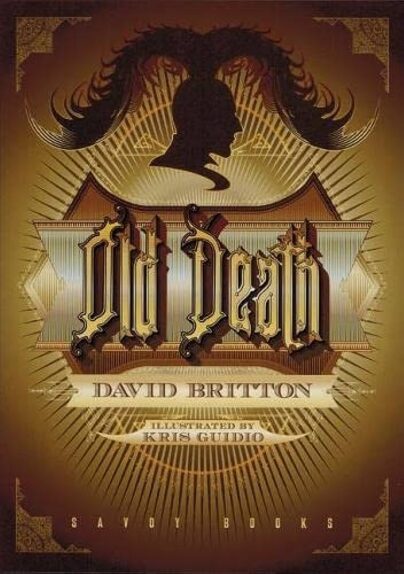

By DAVID BRITTON, KRIS GUIDIO (Savoy Books; 2022)

By DAVID BRITTON, KRIS GUIDIO (Savoy Books; 2022)

This is the posthumously published last novel by David Britton (1945-2020), arguably the most confrontational writer of our time. As with all Britton’s fiction, OLD DEATH is part of the Lord Horror cycle, set in an alternate universe where Nazi Germany has taken over the world, and centered on Lord Horror, a fascist spokesperson based on the British Nazi sympathizer William Joyce, a.k.a. Lord Haw-Haw.

Britton was famously jailed for publishing, through Savoy Books (which he co-founded with Michael Butterworth), the first of the Lord Horror novels in 1989. This is the seventh of them (and so separate from the Lord Horror comics, which include the indispensable REVERBSTORM), and every bit as wild, disreputable and gleefully offensive as its predecessors, with Britton’s none-too-sanguine attitude toward modern sensibilities given full reign in these pages, in which he decries “the politically-correct bollocks of our contemporary times.”

Along for the ride is the late illustrator Kris Guidio (1953-2023), whose tenure with Britton stretches back to a 1986 issue of the Savoy published MENG & ECKER comic. Guidio’s colorful full page renderings, offering spirited depictions of perverse sex, brutality, transformation and an impossible-to-forget dripping rainbow, are done in an intentionally childlike scrawl that offers a perverse thematic compliment to Britton’s prose, despite not matching the letter of the descriptions at all.

The book’s protagonist is Old Death, which is meant quite literally. This personage is, in other words, the Angel of Death, apparently the ultimate manifestation of Lord Horror. Joining him are several recurring characters in the LH universe, such as Meng and Ecker, the once-conjoined twin brothers who rule Auschwitz, as well as the human-Alsatian hybrid “dog boys” and the KRAFT DURCH FREUDE ship, manned by “Blackfaced Orpheus” and his army of genetically-altered dark skinned mutations. Their universe, which will be familiar to anyone who’s read any of the previous Lord Horror books, is suffused by Anti-Semitism, with the characters constantly coming up with new and depraved ways of killing Jews (Britton, keep in mind, was part Jewish), including the “Iron Bone Grinder,” a horrific contraption inspired by an actual Manchester-based amusement park ride.

There’s no real narrative to speak of, with the text packed with extravagant descriptions of mutation and dismemberment. Detailed are an airborne crematorium, a giant metal rooster, eel “cock riders” (you can probably guess what that means), an underworld consisting of “a mélange of Dante, Orpheus, Disneyland, Hitler and NWA’s Compton, among others,” and the mythological figure of Der Struwwelpeter, here tasked with guarding Auschwitz.

The presence of Der Struwwelpeter, from the famous German children’s text of that name, demonstrates a Britton trademark that’s very much present here: his downright compulsive employment of cultural references (something he was doing long before Quentin Tarantino), which often turns the proceedings into an eccentric cataloguing of his literary, musical and filmic influences. Among the shout-outs are Ishmael Reed, THE EXPLOITS OF ENGELBRECHT, JOKER (with “Joaquin Phoenix cynically imitating the real-life Lord Horror”), DELIVERANCE, P.J. Proby, Wyndham Lewis and THE HOUSE ON THE BORDERLAND, while Virginia Woolf and Martin Amis actually figure into the text (in the form of hapless rape victims).

Britton’s own first person observations often interrupt the proceedings, and occasionally offer an explanation for the outrages he describes, which “are nothing if not a world of bad taste. It is no use seeing it from the outside—get in and relive its abomination from the inside!…If the escapades disgust you, that’s the point.”

That Britton was well aware of his terminal condition is evident in the increasing introspection that overtakes the book, and acknowledged outright in a prefatory statement that reads, “I wrote this book while I was dying, to see if I could produce something positive from the experience.” Thinking of OLD DEATH in such terms tends to challenge one’s definition of “positive”; taken as friendly or optimistic the adjective doesn’t quite work, but as laudatory and assured it fits quite well.