By ROLAND TOPOR (Atlas Press; 2018)

By ROLAND TOPOR (Atlas Press; 2018)

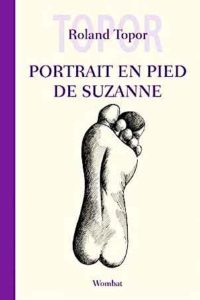

An unspeakably demented concoction that could only have been dreamed up by France’s late Roland Topor. As with JOKO’S ANNIVERSARY, HEAD-TO-TOE PORTRAIT OF SUZANNE appears to have been based off one of the multi-talented Topor’s drawings; said drawing, reproduced in this book, depicts the sole of a foot bearing a naked female torso.

…said drawing, reproduced in this book, depicts the sole of a foot bearing a naked female torso.

That foot belongs to the unnamed narrator, a thoroughly Toporian protagonist. This means a relentlessly self-loathing, gloomy Parisian who among other things is upset over the untimely death of his lover Suzanne. The opening third is essentially a lot of grousing by an unalloyed misanthrope who finds himself fat and unattractive (“That naked body I catch sight of every time I pass the mirror makes me feel like throwing up”), and loathes his current residence in Caracas (“The people who live here pronounce it “Carcass” in their dreary accent”).

“That naked body I catch sight of every time I pass the mirror makes me feel like throwing up”

One night, in quest of food, he enters a strange building whose equally strange proprietors sell him a pair of shoes that are a size too small, causing his left foot to bleed. Yet the wound, located around the base of the Achilles heel, undergoes an odd metamorphosis, becoming a never-closing orifice that’s curiously pleasurable to the touch. It is in fact the mouth (or perhaps a lower orifice) of Suzanne, who’s been reborn in her lover’s foot.

One night, in quest of food, he enters a strange building whose equally strange proprietors sell him a pair of shoes that are a size too small, causing his left foot to bleed. Yet the wound, located around the base of the Achilles heel, undergoes an odd metamorphosis, becoming a never-closing orifice that’s curiously pleasurable to the touch. It is in fact the mouth (or perhaps a lower orifice) of Suzanne, who’s been reborn in her lover’s foot.

As with most resurrected lover narratives (such as SOLARIS), it’s a certainty that this rekindled romance will lead to the same issues that afflicted the relationship the first time around, and indeed things go sour very quickly. Suzanne begins cheating on her lover with a gay man, while the protagonist grows quite manipulative and abusive, leading to a suitably dark and brutal finale.

This novel is not, as is wrongly stated in the introduction by translator Andrew Hodgson, the first English language translation of a Topor text in forty years (Hodgson was evidently unaware of the 1999 Gina Kehayoff publication of Topor’s JE T’AIME), but it is a laudable release. Hodgson’s translation brilliantly captures Topor’s singular voice, which assaults the reader with black humored grotesquerie, paired with a profound sense of alienation, both personal and collective, that registers just as strongly.