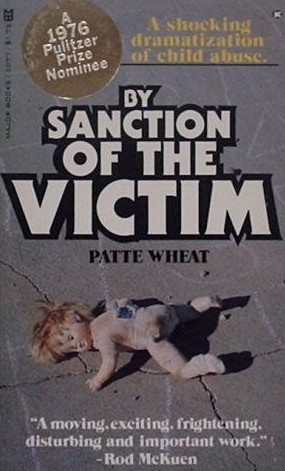

By PATTE WHEAT (Major Books; 1976)

By PATTE WHEAT (Major Books; 1976)

A docu-novel based on the notorious 1965 Sylvia Likens murder, and an object lesson, I believe, in how not to write such a book. The novel is highly problematic, in other words, starting with its conceit of relating the crime entirely from the point of view of the victim. This prevents us from ever learning what drove the perpetrators to do what they did, which in this case is something I’d definitely like to know, and something fiction is uniquely equipped to convey. Check out other, more accomplished novels inspired by the crime such as David Meltzer’s THE MARTYR and Jack Ketchum’s THE GIRL NEXT DOOR, which contain dark insights into the psyches of Likens’ murderers that the more straightforward dramatizations of the case, like John Dean’s INDIANA TORTURE SLAYING, the movie AN AMERICAN CRIME and the novel under discussion, fail to provide.

Sylvia Likens was just 16 when she died in suburban Indiana, a killing that occurred after three months of unspeakable torture at the hands of Sylvia’s guardian Gertrude Baniszewski, the latter’s seven children and several neighborhood kids. In BY SANCTION OF THE VICTIM Patte Wheat transposes the setting to Los Angeles, with the basement where Sylvia suffered much of her torment changed to a garage (basements being quite rare in L.A.) and the time frame whittled down to just two weeks.

Much of what occurs in this novel, including the paddlings, scalding hot bath and branding undergone by the victim, was taken directly from court records, but much was added, presumably to explain away the case’s more inexplicable elements. To show why Sylvia never tried to run away from her tormentors there’s a wholly implausible section in which Marjorie (as Sylvia is renamed) runs away from the home of Florrie (as Gertrude is here identified) and hitchhikes to see her carny parents–who promptly bring her right back! To explain why Sylvia/Marjorie’s little sister did nothing to help, the character, here changed to a little brother, has a dog which Florrie repeatedly threatens to kill if he rats her out. To fully justify Gertrude/Florrie’s sadistic bent she’s made out to be a murderess who successfully hid the corpse of a previous child several years earlier and then told everyone the kid disappeared. Then there’s the fact that in the end of this book (SPOILER ALERT!) Sylvia/Marjorie, in direct opposition to the facts of the real case, somehow survives the abuse.

There are some good things herein. The well written early portions, in which the shy and reserved Marjorie tries and fails woefully to curry favor with Florrie, are quite strong, and will resonate with anyone who’s ever attempted to subside in a hostile environment.

Where the novel gets into trouble is in its latter half, when the abuse escalates. Here the one-note narrative grows quite repetitive and the author increasingly twists reality to fit her agenda. That reality twisting wouldn’t have been such a bad thing if only the fictional additions enhanced the story (as occurred in the above-mentioned novels THE MARTYR and THE GIRL NEXT DOOR), but if anything the changes have the opposite effect, adding distracting artifice and melodrama, and so proving that reality truly is stranger, and in this case far more dramatic, than fiction.