By JOHN DEAN (Borf Books; 1966/99)

By JOHN DEAN (Borf Books; 1966/99)

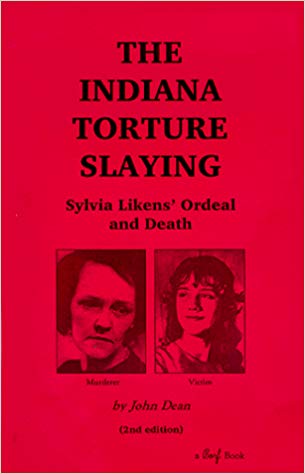

This study of the notorious torture-murder of 16-year-old Sylvia Likens initially appeared within a year of the crime (and was subsequently republished in 2008 as HOUSE OF EVIL), having been compiled from articles written about the case by an Indianapolis Star reporter. Drafted in straightforward reportorial fashion, THE INDIANA TORTURE SLAYING is lacking in psychological insight and delves a little too deeply into the trial of Likens’ killers, but for the most part it’s a solid account, and preferable to other texts on the case like Kate Millet’s THE BASEMENT (whose particulars were admittedly taken from this book) and Patte Wheat’s BY SANCTION OF THE VICTIM.

The book’s opening half covers the particulars of the case. It all began in July 1965, with Sylvia Likens and her younger sister Jenny left by their carny parents in the care of 37-year-old Gertrude Baniszewski and her seven children. Three months later, on October 26, Sylvia died following a prolonged regime of torture. John Dean takes us through the various torments heaped upon Sylvia with reasonable thoroughness—among other things, she was starved, beaten, branded, thrown down stairs, used as a human ash tray, given scalding baths and forced to repeatedly penetrate herself with a Coke bottle.

The monstrous behavior of Gertrude is blamed on an impoverished upbringing and jealousy of Sylvia’s pubescent beauty, while the sadism displayed by Gertrude’s children is ascribed to peer pressure and mob psychology. The book has been widely criticized for such simplistic proselytizing, but since nearly all the participants are now dead, and were never too forthcoming about their actions while they were alive, I think Dean’s conclusions are as authoritative as any—frustrating though it may be, the fact is we’re simply never going to know what possessed Gertrude Baniszewski and her brood to do what they did to Sylvia Likens.

The book’s top-heavy second half, about the trial that followed the murder, is overly detailed (most likely so John Dean could pad his patchwork account to book length), indeed more so than the account of Sylvia Likens’ ordeal. Here Dean insists on bludgeoning us with information on the jury selection process, the witness cross-examination and his own questioning on the stand, all of which can be safely skimmed through, as it’s information I don’t believe we really need.

What we could have used was some info on the thought processes of the jurors who ignored the prosecution’s demand that Gertrude get the death penalty and instead sentenced her to life imprisonment (she was paroled in 1985). That, unfortunately, is about the only court-related info that Dean doesn’t provide, making me conclude that this book would probably have worked better as an extended magazine article.