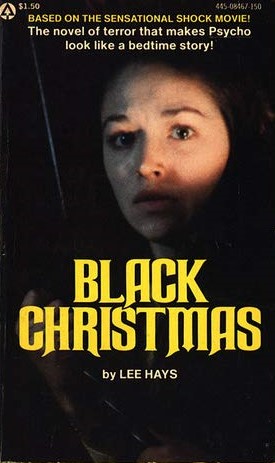

By LEE HAYS (Popular Library; 1976)

By LEE HAYS (Popular Library; 1976)

1974’s BLACK CHRISTMAS, scripted by Ray Moore and directed by Bob Clark, is arguably the granddaddy of holiday horror films, as well as a seminal example of what would come to be known as slasher, or splatter, filmmaking. The irony is that the film, about a maniac loose in a girls’ sorority house on Christmas Eve, is actually fairly restrained in its approach, at least in comparison with the films that followed it. Those films include HALLOWEEN, WHEN A STRANGER CALLS, FRIDAY THE THIRTEENTH and countless Christmas themed horror-fests, very few of which come close to capturing the spare and artful charge of Clark’s film.

This novelization was written by the prolific Lee Hays, who also novelized ONCE UPON A TIME IN AMERICA and several episodic TV tie-ins. It’s probably wrong to criticize this book overmuch, as novelizations are by nature an extremely hasty and disreputable form of literature. It’s true that occasionally a novelization will transcend its limitations, but this one doesn’t.

The major problem with the book is that it spotlights the weaknesses of the script for BLACK CHRISTMAS—of which, it turns out, there are quite a few. The narrative pivots on a series of creepy phone calls to the sorority house in question, which on Christmas Eve is deserted but for three holdouts. The pure-hearted Jess (played in film by Olivia Hussey) is one such holdout. She’s in a fight with her BF Peter because she wants to abort the baby he’s conceived, a decision to which he’s strongly opposed. Then a deranged someone begins making calls to the place, and the inhabitants begin getting murdered. Of course we’re aware from the start that the calls are coming from inside the sorority house, rendering much of the ensuing efforts of the investigating police officers, as they continually attempt to trace the calls, completely redundant from a dramatic standpoint.

But the problems are more than just conceptual. Lee Hays must bear some of the blame for the book’s failure, as is evident in the opening sentence: “It was a gentle snow falling on and around the large Victoria mansion located on the spacious grounds of what had once been the property of the richest man in town.” That, my friends, is what we call a mouthful, and the prose doesn’t improve much as the book advances, with clumsy passages like “The young man was visibly angry but Sergeant Nash on the front desk nearby did not notice it as he extended a warm greeting.” Further confusion is provided by the italicized sections illustrating the caller’s psychotic mindset, although these bits are at least convincingly schizophrenic–something that, for better or worse, can be said for the book overall.