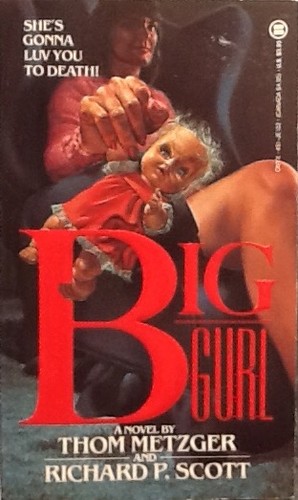

By THOM METZGER, RICHARD P. SCOTT (Onyx; 1989)

By THOM METZGER, RICHARD P. SCOTT (Onyx; 1989)

What the Hell were authors Thom Metzger and Richard P. Scott thinking when they created this near-indescribably nutty concoction? I don’t know, and nor am I entirely sure how to react to BIG GURL, which is either a subversive masterpiece or a horrendously misconceived bit of unalloyed self-indulgence. Either way it was like nothing else on the 1980s horror scene, in which BIG GURL made its unlikely debut as a mainstream paperback.

That Thom Metzger (who now goes by “Th. Metzger”) is a dedicated anarchist shouldn’t surprise anyone (as for co-writer Richard P. Scott, not much is known). Nor should it come as much of a surprise that BIG GURL vanished from circulation very quickly. Metzger attempted to keep it alive via a self-published version in the early nineties and a kindle edition in the 2010s, but all are now long out of print.

This is a novel that in its opening chapter goes clear over the top. We’re introduced to Mary Cup, a.k.a. Big Gurl, a seven foot tall seductress with the mind of a six year old. Living in the attic of a suburban house with her beloved doll Vuvu, she’s under constant threat of being sent back to the group home where she was previously held, although the real mystery is how she was ever let out, as from the start it’s clear that this woman is completely and utterly bat-shit. So too the novel overall, which is drafted in flat “just-the-facts-ma’am” prose that has the paradoxical effect of enhancing the atmosphere of overall craziness.

Mary, who likes to dress in short skirts and spike heels, has a bad habit of killing those who have the misfortune to come into contact with her, starting with a meter man she buries up to his neck in the yard next door to hers. Further victims include a dog she puts in her washing machine, a corrupt priest who gets a bottle jammed down his throat and a new age cultist she crucifies. Her major source of hatred is her abusive father, who’s trying to regain custody of her; Mary, however, has her own plans, and, assisted by Vernon, a social worker who’s none-too-secretly besotted with her, endeavors to give Daddy the most painful send-off of all.

All this is tinged with a satiric tone that takes the edge off the mayhem, and a host of quirky, and often twisted, details (as when Mary brings a dismembered corpse to a climactic shindig, and puts party hats on all the chopped-up body parts). Those things set BIG GURL apart from standard eighties horror novel etiquette, as does the point of view, which never leaves Mary (interspaced with short chapters related in her nonsensical, though quite psychologically revealing, wordage: “So there she is in deepest and dark dungeon with no TV and bug and worm trying to chew her hair and flying scorpion head steal that terrible hamburger they got for her breakfast in bed”). It foregoes, in other words, the standard middle class goodie-goods who tended to dominate such fare, and also the sappy romantic interludes that were often included to leaven the scary business.

There’s no such leavening to be found here, even though the scary business of BIG GURL is never too scary. Outrageous and overwrought, though, it definitely is. If that sounds interesting to you then by all means dig in—good luck finding a copy, though!