By H.P. LOVECRAFT, FRANCOIS BARANGER (Free League; 1936/2020)

By H.P. LOVECRAFT, FRANCOIS BARANGER (Free League; 1936/2020)

The novella-length AT THE MOUNTAINS OF MADNESS, originally serialized in ASTOUNDING STORIES, was one of the highlights of the oeuvre of H.P. Lovecraft. Admittedly quite derivative, of Poe’s NARRATIVE OF ARTHUR GORDON PYM (directly referenced in MOUNTAINS, which doesn’t quite get Lovecraft off the hook) and Hodgson’s NIGHT LAND, AT THE MOUNTAINS OF MADNESS nonetheless has an audacity, ambition and imaginative scope that place it in a category of its own. Ironically for a story that was so derivative, it’s proven extremely influential, with ALIEN and the 1982 THING (to name but a couple examples) bearing its unmistakable influence.

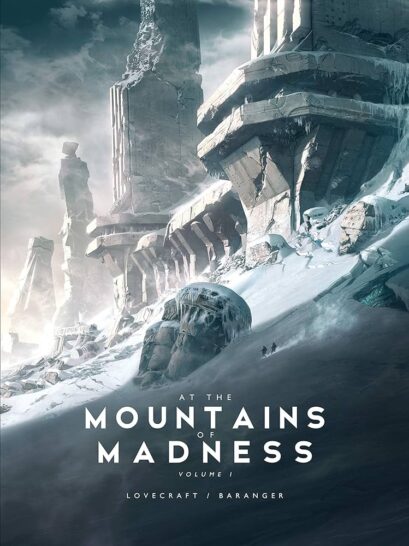

The tale is, for all its imaginative brilliance, not an easy read—hence this illustrated two volume edition, contained in two large format (10.5 x 0.5 x 14.25 inches) hardbacks, which is an excellent way to experience AT THE MOUNTAINS OF MADNESS. The illustrations, nearly all of which take up two full pages (with the text nestled off to the side), were accomplished by the French storyboard artist Francois Baranger, who previously illustrated Lovecraft’s CALL OF CTHULHU in 2019. AT THE MOUNTAINS OF MADNESS is said to be Baranger’s most ambitious work, and it’s a triumph, being almost certainly the finest-ever graphic interpretation of this particular story (which over the years has inspired quite a few such interpretations).

Lovecraft’s tale is set in 1933, and takes the form of an extended recollection by one Professor Dyer. The impetus for his recounting is news of a proposed scientific expedition to Antarctica, following a previous voyage in which Dyer himself was involved. His uncensored remembrance (following a previous recollection in which he omitted the wilder parts) is intended as a warning to the participants of the upcoming expedition.

Dyer’s account, peppered with favored Lovecraftian terms (“aeon,” “subterrene,” “daemoniac,” etc.) and frequent references to the “NECRONOMICON of the mad Arab Abdul Alhazred,” tells of how he and around three dozen fellows navigated many of the same regions explored by Shackleton and others, and, following the lead of an advance group, discovered numerous prehistoric lifeforms preserved by the frozen air. After finding the advance group’s camp devastated, and containing several mutilated corpses, Dyer and a companion fly via airplane—or “aeroplane”—over a vast range of “Mountains of Madness,” on the other side of which lies an alien city in which members of the advance group disappeared, and which contains a still-living entity.

Lovecraft’s descriptions are among his most densely detailed, with a welcome dearth of the “It’s-so-horrifying-I-can’t-describe-it” type of writing in which he had a tendency to indulge. Description, alas, is virtually all we get, as there’s scant dialogue (“Tekeli-li! Tekeli-li!” being all that exists in the way of talk) or alternate perspectives included to alleviate Dyer’s relentlessly dour musings.

Onto the illustrations: drafted in precisely lit, photorealistic hues, Francois Baranger’s magisterial paintings fully befit and even compliment their large format presentation. The illustrations don’t always fully match the descriptions, which is okay, as literal renderings are ill-advised (I base this on previous, more literal, attempts at illustrating this text, which among other sins have depicted the cone-shaped alien structures detailed by Lovecraft as what looks like a sea of Hershey’s kisses).

One more thing: as is increasingly the case these days, the publisher includes a final page disclaimer apologizing for Lovecraft’s archaic worldview: “Lovecraft’s stories deserve to be released and find a new readership, but at the same time, the author’s racism should be approached critically and rejected.” This is a worthwhile publication, but I’m not sure we need guidance on how Lovecraft “should be approached.”