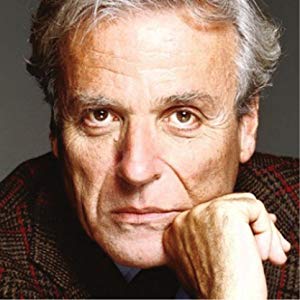

Yet another tragic celebrity death? I’m afraid so. The dear departed this time around is the great William Goldman, one of my longtime heroes. Goldman was a novelist and screenwriter responsible for some of the most iconic entertainment of the 1960s, 70s, 80s and 90s (his output, and his health, admittedly declined in the 00s). It was he who provided the world with such iconic lines as “Follow the money” (from ALL THE PRESIDENT’S MEN) and “Nobody knows anything”—or, more accurately, “NOBODY KNOWS ANYTHING”—as well as the book that contained the latter line, 1983’s ADVENTURES IN THE SCREEN TRADE, which is widely recognized as the world’s premiere screenwriting bible.

Yet another tragic celebrity death? I’m afraid so. The dear departed this time around is the great William Goldman, one of my longtime heroes. Goldman was a novelist and screenwriter responsible for some of the most iconic entertainment of the 1960s, 70s, 80s and 90s (his output, and his health, admittedly declined in the 00s). It was he who provided the world with such iconic lines as “Follow the money” (from ALL THE PRESIDENT’S MEN) and “Nobody knows anything”—or, more accurately, “NOBODY KNOWS ANYTHING”—as well as the book that contained the latter line, 1983’s ADVENTURES IN THE SCREEN TRADE, which is widely recognized as the world’s premiere screenwriting bible.

ADVENTURES IN THE SCREEN TRADE is the Goldman work that has been most widely mentioned in the obituaries that have appeared thus far. It  is indeed a great resource for screenwriters (it’s the only book on the subject that my dad, a thirty year screenwriter, recommended I read), packed as it is with useful advice from a well-seasoned master of the trade, and containing a wealth of enjoyable anecdotes. Plus, it also has that above-quoted line referring to the extent of Hollywood’s knowledge, which has become quite controversial but continues to be widely quoted, simply because it’s entirely accurate.

is indeed a great resource for screenwriters (it’s the only book on the subject that my dad, a thirty year screenwriter, recommended I read), packed as it is with useful advice from a well-seasoned master of the trade, and containing a wealth of enjoyable anecdotes. Plus, it also has that above-quoted line referring to the extent of Hollywood’s knowledge, which has become quite controversial but continues to be widely quoted, simply because it’s entirely accurate.

The other Goldman work that’s been heavily mentioned in the obits is THE PRINCESS BRIDE, for which Goldman penned both the source novel and screenplay adaptation. That book-film combo is indeed a strong one, the 1973 novel in particular; to those who know THE PRINCESS BRIDE only in movie form I’d urge a reading (if not two or three) of the book, as it has an intelligence and complexity missing from the film, and is just as funny.

Beyond that we’re left with an impressive wealth of Goldman novels and screenplays. In the former category are, in addition to THE PRINCESS BRIDE, classics like NO WAY TO TREAT A LADY (1964), a singularly energetic and imaginative example of 1960s-era pulp fiction; MARATHON MAN (1974), Goldman’s unforgettably tough and unsparing take on the espionage thrillers popular in the seventies; MAGIC (1978), Goldman’s one and only horror novel; CONTROL (1982), his loopy nod in the direction of science fiction; and BROTHERS (1986), the engagingly bonkers sequel to MARATHON MAN. I’ll also have to give a shout-out to HYPE AND GLORY (1990), a laugh-out-loud funny piece of reportage and a deeply poignant exploration of middle age ennui in the form of a reminisce about Goldman’s employment as a judge on the 1987 Cannes Film Festival jury and Miss America pageant.

If Goldman never received the respect and adulation as a novelist that he did as a screenwriter, that’s most likely due to the fact that his books fell into that most critically derided form of publishing: popular fiction (thus explaining, in part, Goldman’s lifelong antipathy toward critics, a.k.a. “those assholes” whose reviews, as he liked to boast, Goldman never read). Goldman may not have been the world’s most eloquent prose stylist but he was unquestionably one of the world’s most resourceful, inventive and purely entertaining novelists. Just check out the irresistible first lines of many of his novels: “Aaron would not come out” (from BOYS AND GIRLS TOGETHER), “Every time he drove through Yorkville, Rosenbaum got angry, just on general principles” (from MARATHON MAN), “If there was one place in this world Edith never expected trouble, it was Bloomindale’s” (from CONTROL), “Late on a late Spring afternoon, Chub, ambling across the Oberlin campus, was astonished to see the girl of his dreams break into tears” (from THE COLOR OF LIGHT).

If Goldman never received the respect and adulation as a novelist that he did as a screenwriter, that’s most likely due to the fact that his books fell into that most critically derided form of publishing: popular fiction (thus explaining, in part, Goldman’s lifelong antipathy toward critics, a.k.a. “those assholes” whose reviews, as he liked to boast, Goldman never read). Goldman may not have been the world’s most eloquent prose stylist but he was unquestionably one of the world’s most resourceful, inventive and purely entertaining novelists. Just check out the irresistible first lines of many of his novels: “Aaron would not come out” (from BOYS AND GIRLS TOGETHER), “Every time he drove through Yorkville, Rosenbaum got angry, just on general principles” (from MARATHON MAN), “If there was one place in this world Edith never expected trouble, it was Bloomindale’s” (from CONTROL), “Late on a late Spring afternoon, Chub, ambling across the Oberlin campus, was astonished to see the girl of his dreams break into tears” (from THE COLOR OF LIGHT).

Even lesser Goldman novels like TINSEL (a failed attempt at a “Hollywood à clef” potboiler) and HEAT (a curiously low-energy thriller that was made into an even more stultifying Burt Reynolds movie) were absorbing and satisfying in their way. Those books, incidentally, were written in Goldman’s final years as a novelist, a period during which Goldman fanatic Harlan Ellison claimed his fiction “seemed to me more and more slapdash, more and more written as way-station incarnation on the way to becoming screenplays.”

Screenplays, it seems, were both Goldman’s saving grace and his artistic downfall. He admittedly got stated in the screen trade by accident, when actor Cliff Robertson mistook the manuscript of NO WAY TO TREAT A LADY for a film treatment. Goldman repeatedly claimed he didn’t like or respect screenplays, identifying himself as a novelist first and foremost. Yet Goldman’s screenwriting did eventually overtake his novel writing, which makes sense given that his  novels never attained the type of adulation Goldman received as a screenwriter. On the downside, his final screenwriting credits—which include YEAR OF THE COMET, MAVERICK, THE CHAMBER, THE GHOST AND DARKNESS, DREAMCATCHER and an uncredited polish on LAST ACTION HERO—were nothing to write home about.

novels never attained the type of adulation Goldman received as a screenwriter. On the downside, his final screenwriting credits—which include YEAR OF THE COMET, MAVERICK, THE CHAMBER, THE GHOST AND DARKNESS, DREAMCATCHER and an uncredited polish on LAST ACTION HERO—were nothing to write home about.

That does not, however, blunt the impact of Goldman’s best work in the field. I’ll confess I never much cared for BUTCH CASSIDY AND THE SUNDANCE KID, Goldman’s breakthrough work in the field, as a movie, but in screenplay format it’s pure magic, being perhaps the most eminently readable script I’ve ever encountered (it’s a better read than most novels).

Other great Goldman scripts include his adaptation of Stephen King’s MISERY, which succeeded in synthesizing all the good things about King’s novel while smartly jettisoning the not-so-good elements (and for a time made Goldman the go-to guy for King adaptations), MARATHON MAN, in which Goldman performed a similar feat on his own novel, and ALL THE PRESIDENT’S MEN, in which Goldman managed to fashion a riveting piece of drama from decidedly undramatic material. All of those scripts, incidentally, are available in book form, courtesy of the Applause Books volumes FOUR SCREENPLAYS (1995) and FIVE SCREENPLAYS (1996), which I enthusiastically recommend to anyone interested in quality scriptwriting—or just a good read.

About Goldman’s demise, the one and only positive thing I can say it that might just spur the critical reappraisal William Goldman never received in his lifetime. Be it as a novelist, screenwriter or memoirist, Goldman was one of the great American writers, and it’s high time he was properly recognized as such.

About Goldman’s demise, the one and only positive thing I can say it that might just spur the critical reappraisal William Goldman never received in his lifetime. Be it as a novelist, screenwriter or memoirist, Goldman was one of the great American writers, and it’s high time he was properly recognized as such.