It certainly seemed like a good idea: a 1992-94 Russian American co-production in which six world class directors were tasked with providing hour-long documentary interpretations of “the gigantic cinematic canvas of historical change in Russia,” each with a different subject. The line-up, corralled by World Vision Enterprises and Russian American producer Ira Barmak (SILENT NIGHT, DEADLY NIGHT) was impressive: Peter Bogdonovich (whose focus was on Russian feminism), Ken Russell (culture), Jean-Luc Godard (history), Werner Herzog (faith), Nobuhiko Obayashi (children) and Federico Fellini (emotion). The proposed title: MOMENTOUS EVENTS, reflecting both the massive changes occurring in the former Soviet Union and the perceived importance of the project.

The late eighties and early nineties were certainly a banner era for eccentric film and TV anthology projects. Examples include ARIA (1987), in which ten famous directors dramatized their favorite operas; BRISE-GLACE (1988), in which Raul Ruiz and two other filmmakers filmed linked shorts aboard a Swedish icebreaker; and A TV DANTE: THE INFERNO (1989), in which Ruiz and Peter Greenaway interpreted portions of Tom Phillips’ translation of Dante’s INFERNO. Had it been completed, the $12 million MOMENTOUS EVENTS would have been the most ambitious of the lot, a six hour multi-parter with a wraparound segment set to be scripted by DERSU UZALA’s Yuriy Nagibin. Alas, it wasn’t to be.

The problems, it seems, began almost immediately. Fellini died in 1993, before filming on his segment began, while Bogdonovich never completed (or, as far as I’m aware, started) his film. Ira Barmak, who initiated the project, also passed in 1993, followed by Yuriy Nagibin in 1994, leaving the wraparound unscripted and, by extension, unfilmed.

Ultimately only four of the proposed six films were completed: Herzog’s BELLS FROM THE DEEP: FAITH AND SUPERSTITION IN RUSSIA/Glocken aus der Tiefe—Glaube und Aberglaube in Rußland, Russell’s ALICE IN RUSSIALAND, Godard’s THE KIDS PLAY RUSSIAN/Les Enfants jouent à la Russie, and Obayashi’s RUSSIAN LULLABIES, with the Russell and Godard films released on the festival circuit as a double feature (entitled RUSSIA IN THE 90s) and the Herzog and Obayashi segments exhibited as standalone films.

Momentous these films weren’t. These days, in fact, they tend to be treated as mere footnotes in their makers’ filmographies (ALICE IN RUSSIALAND, for its part, is now an example of Lost Media, with the only current source being a poor quality VHS dub uploaded to YouTube), with the MOMENTOUS EVENTS project having been permanently memory holed.

Still, with directors as talented and individual as these, the films can’t be ignored. If nothing else, they constitute a peerlessly eclectic grouping of filmmakers whose approaches couldn’t be more divergent, although I’m not too sure they properly convey the slice-of-life portrait of Russian society that was intended (which would have required filmmakers who were themselves Russian).

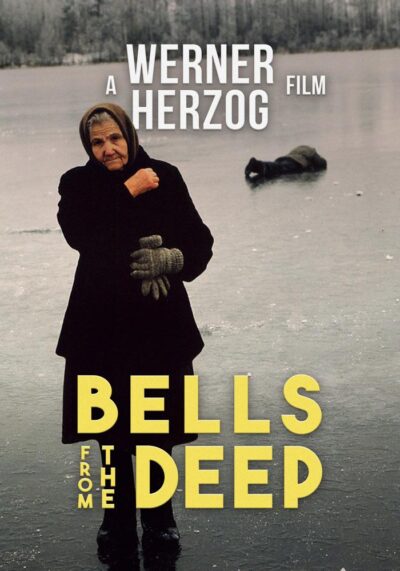

The first “Momentous Event” to be completed was BELLS FROM THE DEEP, a sober and straightforward yet quite bizarre little film that compares favorably with Werner Herzog’s earlier anthropological reveries HERDSMEN OF THE SUN/Wodaabe—Die Hirten der Sonne. Nomaden am Südrand der Sahara (1989) and JAG MANDIR/Jag Mandir: Das exzentrische Privattheater des Maharadscha von Udaipur (1991). It handily exemplifies Herzog’s none-too-orthodox conception of documentary filmmaking, meaning a great deal of the “reality” on display was scripted and staged.

BELLS FROM THE DEEP (Clip)

Included are depictions of religious ceremonies, dramatic exorcisms, an infant undergoing what looks like a traumatic baptism and a description of the mythical sunken city of Kitezh, with people making pilgrimages to its alleged resting place in Central Russia’s Lake Svetloyar. Those pilgrims are depicted crawling on four legs (a probable example of Herzogian invention), which offers up the film’s most striking and bizarre scene, in which we see two men crawling on their bellies across the frozen Lake Svetloyar while in the foreground a peasant woman describes a ghostly encounter. The film concludes with a Jesus-like figure addressing the camera and intently blessing the viewer.

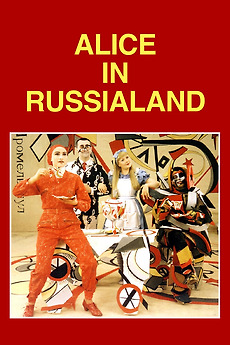

Switching gears rather dramatically, we come to ALICE IN RUSSIALAND, an unrestrained Ken Russell kitsch-fest. Viewers familiar with Russell’s late period filmography (particularly A BRITISH PICTURE and THE FALL OF THE LOUSE OF USHER) will recognize the homemade sets, cheap-looking video imagery and cheerfully outrageous tone. Those things are employed in the service of a (very) free adaptation of Lewis Carroll’s ALICE IN WONDERLAND in which a thirtyish Alice (Russell’s then-wife Hetty Baynes) is seen entering “Russialand.” There a baby—Russia—is coveted by a hammer-and-sickle wielding man and gaudily dressed folk, representing famous Russian figures like Dmitri Shostakovich (who takes the form of the Mad Hatter) and Josef Stalin (the Queen of Hearts), cavort, with the latter taking Carroll’s immortal “Off with their heads!” line quite literally.

That covers the film’s first half, which concludes with the appearance of Russell himself as Glasnost (the Cheshire Cat). Much of ALICE IN RUSSIALAND’s second half is taken up with documentary footage of the actual Glasnost’s impact on Russian culture, overlaid with voice-over dialogue by Russell, who instructs Alice on the particulars of Russian punk rock, the Necrorealism art movement, Russian kiddie cartoons and the “garage music” of Major Brown’s Portable Orchestra.

Final verdict: ALICE IN RUSSIALAND, with its unwieldy combination of campy symbolism and documentary reality, doesn’t quite work (not least because Russell doesn’t appear to know the difference between history and culture), but it’s too much fun to complain about overmuch.

I can, however, complain about the Godard perpetrated KIDS PLAY RUSSIAN. It has the distinction of being the first film I ever walked out of midway through (when it screened at the 1994 Vancouver Film Festival as part of the abovementioned RUSSIA IN THE 90s program), and now, having viewed it in its entirety, I can confirm that it’s every bit as insufferable as it seemed back in ‘94 (and that I didn’t miss much by leaving before it was over).

In contrast to the cheery optimism of ALICE IN RUSSIALAND, THE KIDS PLAY RUSSIAN is dour and whiney, not to mention stultifyingly pretentious. It’s been described as “an incantation of the deeper questions concerning the Russian soul,” consisting of a flow of staged and documentary images, often superimposed over one another in a manner that admittedly seemed innovative in the early nineties. The soundtrack consists primarily of random bitching by Godard about subjects ranging from then-MPAA head Jack Valenti (identified as “that idiot”), Steven Spielberg, American culture and Russia itself, which Godard views as having been irretrievably damaged by the intrusion of western capitalism.

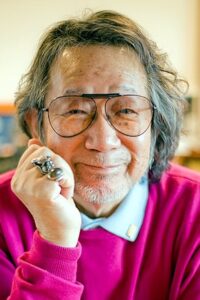

Finally, we have RUSSIAN LULLABIES by Nobuhiko Obayashi, a sweet natured palate-cleanser. Obayashi was largely unknown in the western world in the early 1990s, and joined the MOMENTOUS EVENTS project after an offer was made to Akira Kurosawa, who declined but suggested Obayashi (who made a 1990 documentary on Kurosawa’s DREAMS) in his place. Obayashi has since become semi-famous in the English speaking world for the outrageous cult item HOUSE (1977), so his inclusion no longer seems as inappropriate as it once did.

RUSSIAN LULLABIES (Complete Documentary)

His is the most unorthodox approach, with Obayashi essentially ceding his job as director. This is to say that filming was accomplished entirely by five Russian families, who in 1992 were given camcorders and asked to document their day-to-day lives. This results in a montage of not-very-distinguished handheld camerawork and a variety of postproduction video effects, created by Obayashi to liven things up.

Contained are depictions of animals (including piglets being birthed), snowstorms, food preparation, field plowing and much culturally specific song and dance, as well as unpleasant elements like toxic sewage, an interminable 18 hour train ride and an old woman’s observation that in her earlier years “we didn’t have to work until we died, unlike now.” The unshowy immediacy Obayashi appears to have been aiming for is evident, but what’s missing is any sense of demarcation between the participants, because the people, like the rural settings on display, all look the same.