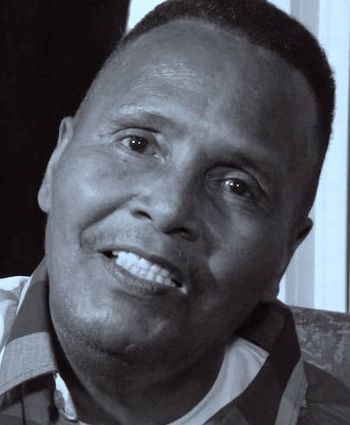

The so-called Blaxploitation era of the 1970s turned out several African American filmmakers who could be termed auteurs. There was Melvin van Peebles, who wrote, produced, directed and starred in SWEET SWEETBACK’S BAADASSSSS SONG (a film that’s often credited with kick-starting the whole cycle), as well as the comedian-turned-movie-impresario Rudy Ray Moore, of DOLEMITE and its follow-ups, and also the nervy and resourceful Jamaa Fanaka (1942-2012), whose career path was different from those of any of his blaxploitation contemporaries and, for that matter, any filmmaker.

The so-called Blaxploitation era of the 1970s turned out several African American filmmakers who could be termed auteurs. There was Melvin van Peebles, who wrote, produced, directed and starred in SWEET SWEETBACK’S BAADASSSSS SONG (a film that’s often credited with kick-starting the whole cycle), as well as the comedian-turned-movie-impresario Rudy Ray Moore, of DOLEMITE and its follow-ups, and also the nervy and resourceful Jamaa Fanaka (1942-2012), whose career path was different from those of any of his blaxploitation contemporaries and, for that matter, any filmmaker.

Fanaka was born with the very white-sounding name Walter Gordon (he came up with his chosen moniker, he claimed, by perusing a Swahili dictionary, with Jamaa meaning “family,” “brotherhood” and “togetherness,” and Fanaka “progress” and “success”). He enjoyed the distinction of having made his first three features as student projects for the UCLA film program (apparently getting an A on each). John Carpenter and Dan O’Bannon performed a similar feat with the USC student film DARK STAR, which ended up scoring a theatrical release in 1974, but having three such projects released commercially is unheard of, then and now. Yet Fanaka pulled it off, and in so doing turned out what remain his two most impacting films: WELCOME, BROTHER CHARLES and PENITENTIARY.

First, though, he made 1972’s 16 minute A DAY IN THE LIFE OF WILLIE FAUST, OR DEATH ON THE INSTALLMENT PLAN, credited to Fanaka’s birth name. A very loose adaptation of Goethe’s FAUST, it concerns a heroin-addicted young black man (Fanaka) trying to maintain a “normal” existence as a husband and father while feeding his habit. The film is of note primarily for its documentary-like portrayal of life in South Central LA (via verite imagery that’s rarely in focus), and for featuring one of the ugliest shooting-up scenes ever, with an extreme close-up of a needle piercing flesh, and a gout of blood when said needle is yanked out.

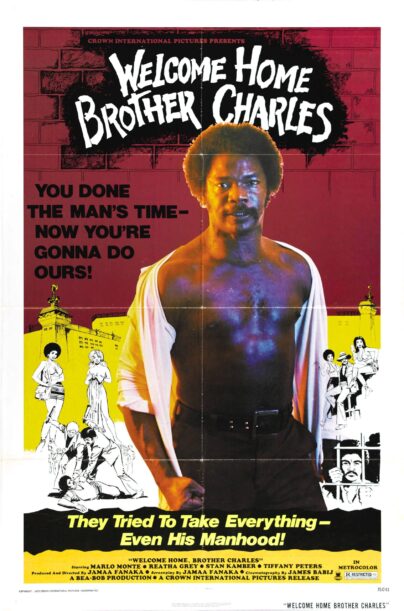

Onto the feature-length WELCOME HOME, BROTHER CHARLES, completed in 1975 and released the following year (and later on video, in cut form, as SOUL VENGEANCE). Fanaka’s characterization of it as “a work of art of the highest order” may be a bit hyperbolic, but it was an impressive feature debut, offering a highly individual mixture of thoughtful drama and unadulterated sleaze. Fanaka had an instinct for the type of action-oriented sensationalism that characterized Blaxploitation flicks, yet also imparted a note of downright Lynchian strangeness. The mixture was far from harmonious (as Fanaka had yet to fully come into his own as a filmmaker), but resulted in an altogether fascinating oddity.

Onto the feature-length WELCOME HOME, BROTHER CHARLES, completed in 1975 and released the following year (and later on video, in cut form, as SOUL VENGEANCE). Fanaka’s characterization of it as “a work of art of the highest order” may be a bit hyperbolic, but it was an impressive feature debut, offering a highly individual mixture of thoughtful drama and unadulterated sleaze. Fanaka had an instinct for the type of action-oriented sensationalism that characterized Blaxploitation flicks, yet also imparted a note of downright Lynchian strangeness. The mixture was far from harmonious (as Fanaka had yet to fully come into his own as a filmmaker), but resulted in an altogether fascinating oddity.

The title character, played by Marlo Monte (whose only imdb credit this is), lives in Watts, CA. As with A DAY IN THE LIFE OF WILLIE FAUST, the film was lensed amid actual residents of the community, who rarely stand still, frolicking and jumping around even in the midst of dramatic scenes (a similar slice-of-life aesthetic was sought by director Charles Burnett, a fellow UCLA classmate and cameraman on WELCOME HOME, BROTHER CHARLES, in his own 1978 debut feature KILLER OF SHEEP). The exploitation business kicks in when Brother Charles is beaten up and nearly castrated by a corrupt white cop, and imprisoned by an equally corrupt judge.

It’s after this that the strangeness, heralded by an opening credits sequence depicting a wooden African figurine bearing an oversized penis, underscored by a profoundly eerie and discordant saxophone wail (recorded in a UCLA studio), really kicks in. Charles undergoes experiments in prison that cause his penis to grow to an insane length, and upon being released he uses it to strangle his tormentors and seduce their wives. Aside from being insanely out-of-left-field, this development would appear to bolster a particularly egregious black male stereotype, although Fanaka claims his aim was to “debunk that myth of Black sexual superiority based upon the size of the sexual equipment.”

Likewise, the ending, in which Brother Charles meets his maker via suicide, and is encouraged in so doing by his girlfriend (Reatha Grey), would appear to be an unalloyed wallow in ghetto nihilism, yet Fanaka argued otherwise: “Let’s face it, his life was over. She didn’t want him to become a research monkey.”

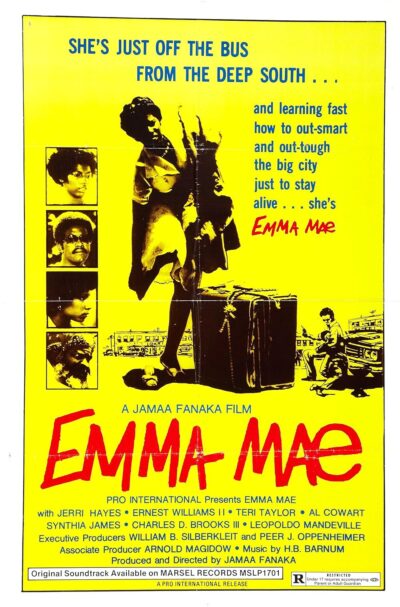

Fanaka’s next UCLA diploma project-turned-big-screen-spectacular was 1976’s EMMA MAE (a.k.a. BLACK SISTER’S REVENGE). A far more confident and streamlined work, EMMA MAE once again mixes naturalistic drama and exploitation, but without the redeeming strangeness of WELCOME HOME, BROTHER CHARLES, for which reason EMMA MAE emerges as a letdown.

Featured is Jerri Hayes (who like Marlo Monte has no other imdb credits) as the title character, a young woman hailing from Mississippi (Fanaka’s home state) who’s staying with family in LA. There she falls in love with Jessie (Ernest Williams III), a lowlife for whom Emma risks her freedom after he’s thrown in jail. She masterminds a bank robbery to raise bail money, only to discover that Jessie never really cared for her. She resolves to leave, but before doing so warns Jessie that “I’m gonna kick yo ass!,” and makes good on the promise.

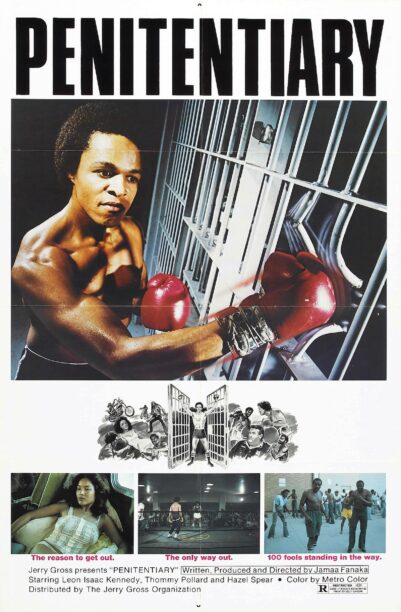

There followed Fanaka’s third, and most successful by far, student-made feature: 1979’s PENITENTIARY. Appropriately for a writer-producer-director whose previous films pivoted on incarceration, it takes place in a prison (portions of which were filmed in an actual jail, while others were lensed on the UCLA campus). It brings back the grit and strangeness of WELCOME HOME, BROTHER CHARLES, including that film’s aforementioned saxophone wail, which is reprised on PENITENTIARY’S soundtrack. Also present is camerawork that utilizes wide angle lenses to create an interesting, and at times eerie, effect.

Leon Isaac Kennedy plays Martel “Too Sweet” Gordone, who like Brother Charles before him is unjustly incarcerated. The catalyst is a prostitute (Hazel Spear) who kills a biker in a desert bar and frames Too Sweet for the murder. He ends up in an all-black prison whose inmates include colorful figures like Sweet’s psychopathic cellmate “Half Dead” (Badja Djola), who upon trying to rape Sweet initiates one of the most overtly homoerotic fight scenes in film history (involving lots of sweating and straining by two barely-dressed men); the elderly “Seldom Seen” (Floyd ‘Wildcat’ Chatman), who teaches Sweet how to endure the grind of prison existence; and the “Gay Boxing Spectator” (Warren Bryant), actually a transsexual whose flamboyant antics evidently fascinated Fanaka (as he continually cut to them).

Leon Isaac Kennedy plays Martel “Too Sweet” Gordone, who like Brother Charles before him is unjustly incarcerated. The catalyst is a prostitute (Hazel Spear) who kills a biker in a desert bar and frames Too Sweet for the murder. He ends up in an all-black prison whose inmates include colorful figures like Sweet’s psychopathic cellmate “Half Dead” (Badja Djola), who upon trying to rape Sweet initiates one of the most overtly homoerotic fight scenes in film history (involving lots of sweating and straining by two barely-dressed men); the elderly “Seldom Seen” (Floyd ‘Wildcat’ Chatman), who teaches Sweet how to endure the grind of prison existence; and the “Gay Boxing Spectator” (Warren Bryant), actually a transsexual whose flamboyant antics evidently fascinated Fanaka (as he continually cut to them).

Running the prison is Lieutenant Ainsworth (future PORKY’S alum Chuck Mitchell), who organizes a boxing tournament. Like a warped variant on ROCKY, the film pivots on boxing as a means of establishing one’s self-worth, with the scrappy Too Sweet entering the tournament in the hope of winning the grand prize: parole. I wouldn’t dream of revealing how it all works out.

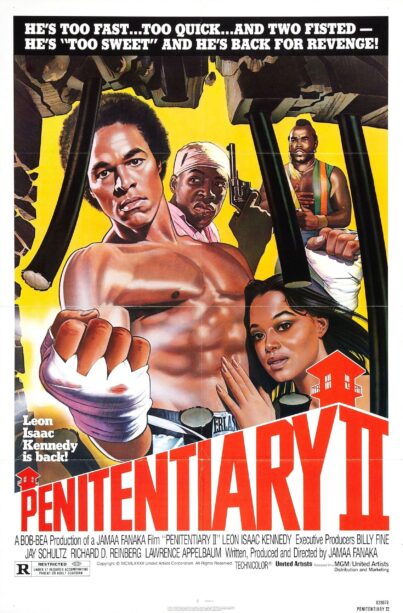

PENITENTIARY was successful enough that it inspired a sequel. 1982’s PENITENTIARY II, alas, was made outside the auspices of UCLA, which may explain why it feels so uninspired. The visual and musical quirks that distinguished the earlier film and its antecedents were jettisoned in favor of a wholly conventional, if occasionally quite brutal, treatment.

Here we find Too Sweet living with his sister (Peggy Blow) and her husband (Glynn Turman) in Compton, CA. Sweet hooks up with an old flame (Eugenia Wright), but she’s brutally dispatched (in a garishly lit scene that once again proves Fanaka’s facility for exploitation) by Half Dead (played here by Ernie Hudson), who’s escaped from prison and is determined to even the score with Sweet. This results in Sweet re-entering the boxing ring, with Mr. T (in his premiere film appearance) as his coach, and Warren Bryant turning back up to represent the gay contingent.

up with an old flame (Eugenia Wright), but she’s brutally dispatched (in a garishly lit scene that once again proves Fanaka’s facility for exploitation) by Half Dead (played here by Ernie Hudson), who’s escaped from prison and is determined to even the score with Sweet. This results in Sweet re-entering the boxing ring, with Mr. T (in his premiere film appearance) as his coach, and Warren Bryant turning back up to represent the gay contingent.

Also featured is the always-watchable Tony Cox. Credited simply as “Midget,” Cox is on hand for some dumb-assed comic relief, but has a memorable end credits appearance in which he mugs shamelessly in the foreground of a group photo, showing that Fanaka hadn’t entirely lost his taste for the oft-kilter.

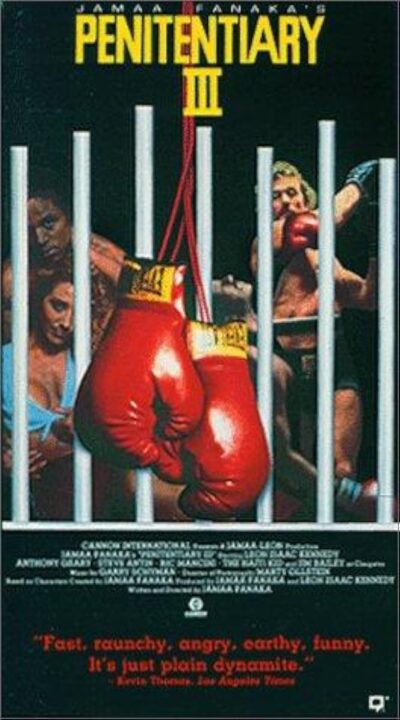

Speaking of which: PENITENTIARY III arrived in 1987, and it’s even farther removed from Fanaka’s early aesthetic. A product of the notorious Cannon Group, PENITENTIARY III was the only one of Fanaka’s features he didn’t personally own. It makes sense, then, that it feels so impersonal, packed with 1980s movie mainstays (smoky photography, synthesizer music, over-applied eye shadow, etc.) and white people (an element that was previously quite sparse in Fanaka’s filmography). It also contains the Haitian accented wrestler Raymond Kessler, a.k.a. Haiti Kid, as “Midnight Thud,” a dwarf residing in a dungeon(!) underneath a penitentiary.

Obviously any and all attempts at naturalism were jettisoned in PENITENTIARY III, with Too Sweet ending up in Midnight Thud’s orbit after killing a man in a boxing match due to imbibing a drink spiked with a performance-enhancing drug. Sweet takes on Midnight Thud, who’s released into Sweet’s cell by the corrupt warden (GENERAL HOSPITAL’s Anthony Geary), in a ludicrously protracted fight that will likely seem pointlessly excessive to anyone who hasn’t seen the first PENITENTIARY, as the fight in question riffs directly on the Too Sweet-Half Dead prison cell scuffle.

Obviously any and all attempts at naturalism were jettisoned in PENITENTIARY III, with Too Sweet ending up in Midnight Thud’s orbit after killing a man in a boxing match due to imbibing a drink spiked with a performance-enhancing drug. Sweet takes on Midnight Thud, who’s released into Sweet’s cell by the corrupt warden (GENERAL HOSPITAL’s Anthony Geary), in a ludicrously protracted fight that will likely seem pointlessly excessive to anyone who hasn’t seen the first PENITENTIARY, as the fight in question riffs directly on the Too Sweet-Half Dead prison cell scuffle.

Yet Midnight Thud undergoes a change of heart, and becomes a Yoda-like mentor to his onetime opponent (despite the fact that Too Sweet won their initial fight). The results of his efforts are made manifest in yet another climactic boxing match, which is, needless to say, the most ridiculous and overwrought such sequence in the entire trilogy.

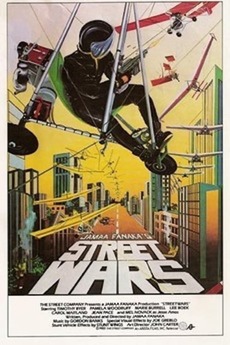

Fanaka made one more feature: 1991’s STREET WARS, a no-budget addition to the hood dramas that proliferated in the 1990s. Any comparisons with STREET WARS and BOYZ IN THE HOOD or MENACE II SOCIETY, however, are rendered superfluous by Fanaka’s script, which contains a drive-thru crack house and paragliding fly-by shooters, and his filmmaking, which has all the hard-hitting realism of an episode of COP ROCK. I honestly wondered if the film wasn’t intended as a parody of hood dramas (a la DON’T BE A MENACE TO SOUTH CENTRAL WHILE DRINKING YOUR JUICE IN THE HOOD), but it seems Fanaka’s intent was entirely serious.

Fanaka’s final productions, aside from a never-completed documentary called HIP HOP HOPE, were a succession of doomed lawsuits. Fanaka’s initial suits, filed against the DGA, were all were dismissed in their early stages, and got Fanaka declared a “vexatious litigant,” but that didn’t slow him down. In 2000 he made his grandest filing yet, a class action lawsuit against all the major Hollywood studios for being in violation of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 This gambit didn’t go any farther than the others, but Fanaka was undeterred, eagerly publicizing the lawsuit on his DVD audio commentaries for PENITENTIARY and PENITENTIARY II. Maybe Jamaa Fanaka, who died in Los Angeles on April 1, 2012, might have been better off seeking funding for a new movie, although given the quality of his final films perhaps things worked out just as they should have.

doomed lawsuits. Fanaka’s initial suits, filed against the DGA, were all were dismissed in their early stages, and got Fanaka declared a “vexatious litigant,” but that didn’t slow him down. In 2000 he made his grandest filing yet, a class action lawsuit against all the major Hollywood studios for being in violation of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 This gambit didn’t go any farther than the others, but Fanaka was undeterred, eagerly publicizing the lawsuit on his DVD audio commentaries for PENITENTIARY and PENITENTIARY II. Maybe Jamaa Fanaka, who died in Los Angeles on April 1, 2012, might have been better off seeking funding for a new movie, although given the quality of his final films perhaps things worked out just as they should have.