According to the late Harlan Ellison, “If, in (sixty-two) years as a professional writer, I have had anything approaching a ‘universal hit,’ then surely the most logical choice would be the stories of Vic and Blood.” He’s referring to the handful of strange yet wondrous tales, spanning the years 1969 to 2003, about Vic, a teenage punk, and his telepathic dog Blood, who subsist in a post-nuclear wasteland.

That was the premise of “A Boy and His Dog,” a novella published in abridged form in the April 1969 issue of NEW WORLDS magazine, and in its full 18,000 word length in the July 1969 collection THE BEAST THAT SHOUTED LOVE AT THE HEART OF THE WORLD. It’s very much in keeping with Ellison’s output of the time, which tended toward the nasty and upsetting; blistering tales like “Along the Scenic Route,” “Knox” and the infamous “I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream” evidence those tendencies, as does Ellison’s introduction to his 1974 collection APPROACHING OBLIVION, which non-ironically informs its readers that “You’re approaching oblivion, and you know it, and you won’t do a thing to save yourselves…And if you hear me sobbing once in a while, it’s only because you’ve killed me, too, you fuckers.”

Such vitriol is on full display in “A Boy and His Dog.” Vic the teenage punk relates the story through a hard-boiled first person viewpoint that sounds remarkably like the “rapid jive-talking shoot-from-the-hip Nervous-Norvus mode of conversation” Stephen King claimed Ellison himself utilized. Blood, a product of pre-nuke genetic experimentation, uses his superior intelligence to locate women for Vic to rape, with food and shelter being the reward. “I’ve purposely reversed the roles of beast and human,” Ellison wrote. “The people in this story act like animals. The dog acts in the noblest traditions of humanity at its best.”

Eventually Blood sniffs out an unwilling female, a seductress named Quilla June, under whose spell Vic immediately falls. After a tryst in a devastated gymnasium, and a gunfight with a band of marauders, Quilla June double-crosses Vic and runs off, leaving behind a key card.

The card opens a drop shaft that leads to a secluded underground community. Vic leaves Blood behind and ascends the shaft, emerging in “a town that looked for all the world like a photo out of one of the waterlogged books in the library on the surface,” whose residents, Quilla June among them, practice “lying, hypocritical crap they call civility.” They seek to turn Vic into a one-man stud farm, as all the men in this community have gone sterile (“No wonder the men couldn’t get it up and make babies that had balls instead of slots”).

He and Quilla June escape, heading back up to the surface to rendezvous with Blood—who’s near death and desperately needs sustenance. What is Vic to do? The answer is revealed in the morbid yet touching denouement, which is topped off with an impossible-to-forget final line.

“A Boy and His Dog” was popular enough to bequeath a screen adaptation that, in a rarity for Ellison (whose writings inspired quite a few unmade films), actually made it to production. The writer-director was the late character actor L.Q. Jones (1927-2022), a Sam Peckinpah regular and one of the driving forces behind the 1971 horror-fest THE BROTHERHOOD OF SATAN. Ellison was contracted the write the screenplay, but only managed 14 pages before exhaustion forced him to abandon it (a saga profiled in Ellison’s 2003 essay “Huck and Tom: The Bizarre Liaison of Ellison and Jones”). Thus Jones himself ended up scripting the 1974 film, winding up with a (mostly) faithful rendering of the novella.

It’s a little raw in spots, and the micro-budget is painfully apparent throughout, but A BOY AND HIS DOG remains one of the truly significant cult films of the seventies. Vic is played by a young Don Johnson (in one of many adventurous early 1970s film choices—others included THE MAGIC GARDEN OF STANLEY SWEETHEART and ZACHARIAH), and Blood by the scruffy mutt who essayed “Tiger” in THE BRADY BUNCH, paired with vocals by Tim McIntire. Quilla June is incarnated by Susanne Benton, while Jason Robards plays the leader of the underground society, whose residents for some reason wear clownish facial makeup.

The apocalyptic universe is a fully realized and convincing one, and the film is graced with one of the all-time great opening shots (blunted somewhat by a superfluous nuclear explosion prologue that was added in the eighties). The finale isn’t bad either, although it replaces the novella’s heartfelt concluding line with a smart-assed pun that enraged Ellison to no end.

A BOY AND HIS DOG wasn’t anyone’s idea of a box office success, which explains why Jones never directed another feature. Yet Ellison kept the film alive, hosting a disastrous screening at the World Science Fiction Convention, where he entertained the crowd between all the film breaks (the pic went on to win a Hugo Award), and turning up for meet-and-greets at revival screenings. He also furthered the saga in print, as “Over the years I came to realize that the novella had only been part of the story; that to tell the adventures of Vic and Blood properly, a larger body of writing would have to continue the narrative.”

That “larger body” commenced with the 1977 short story “Eggsucker” (which appeared in the anthology ARIEL: THE BOOK OF FANTASY Volume 2). A prequel to “A Boy and His Dog,” it’s told from the highly erudite, cynical POV of Blood—who, as with Vic’s “Boy and His Dog” narration, sounds remarkably like Harlan Ellison. Blood relates how he and Vic first met (Vic was twelve at the time), and how they live in perpetual fear of gangs of homicidal pederasts roaming the wasteland. A well told tale, but the conclusion is annoyingly open-ended.

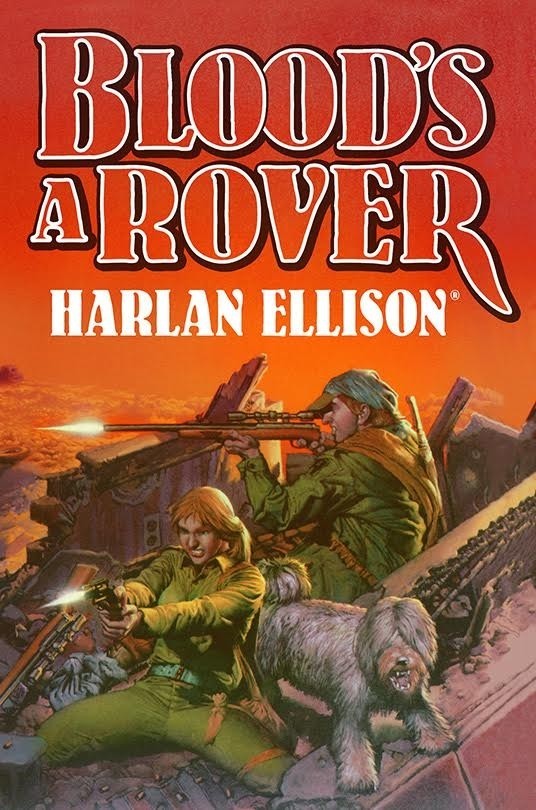

“Eggsucker’s” primary worth was as a preamble for a teleplay entitled BLOOD’S A ROVER, written in May-August of 1977. It was intended as the two-hour pilot of a proposed series for NBC, who ultimately passed (Ellison later claimed he “always expected them to”), but the script eventually saw publication in 2018.

BLOOD’S A ROVER introduces a new character: Spike, a young woman “solo” who’s tougher than Vic and Blood put together, and serves, it would seem, as a rejoinder to claims that “A Boy and His Dog” was misogynistic. Spike is able to receive Blood’s telepathic communication, which apparently proves she’s an “exceptional person” (something Vic most definitely isn’t, so how is he able to hear Blood’s thoughts?).

As BLOOD’S A ROVER begins Vic is nowhere to be seen, having been felled by mutant spiders (an event described in the story “Run Spot, Run,” which appeared three years after this teleplay—see below). He shows up in the second act, thus turning a duo into an unlikely trio whose greatest obstacle, aside from a psychopathic gang leader named Fellini and his goons, is Vic’s ingrained sexism; as Spike scolds, “If you could get beyond your slopebrowed, prognathous-jawed Cro-Magnon sexist thinking, you might be able to stay alive till next week.”

Ellison had an undeniable talent for screenwriting, and provides a gripping and exciting “brain movie.” It’s easy to understand, though, why NBC passed on the project. A familiarity with the events of “A Boy and His Dog” and “Eggsucker” is a requisite, and Spike is simply too good to be true. Impossibly strong, wise and pure-hearted, she’s very much an idealized personage, and so out of place in a saga whose major selling point is brutal honesty.

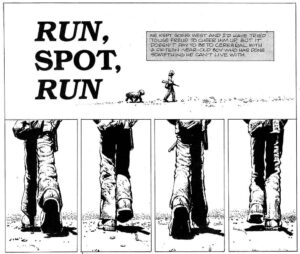

Next in the V&B line-up was the story “Run Spot, Run,” published in 1980 (in the September/October issue of MEDIASCENE PREVUE). Told once again from Blood’s vantage, it occurs directly following the events of “A Boy and His Dog.” Blood has eaten the special meat Vic prepared for him (note that Quilla June has disappeared, though not into thin air), and finds himself tormented by horrific visions from Vic’s subconscious. The two then get chased into a patch inhabited by giant spiders, who entrap Vic in a massive web and leave Blood to forage on his own. Not a bad story, but it could have stood to be a bit longer.

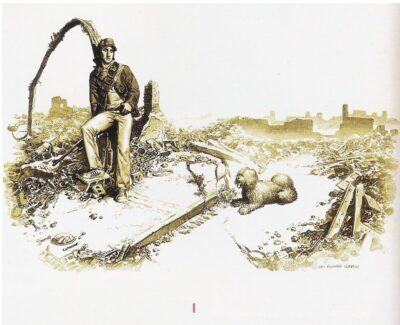

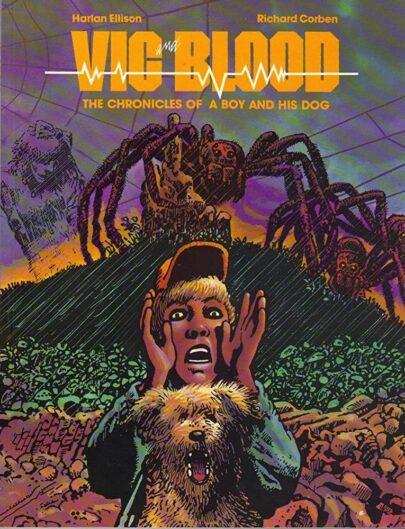

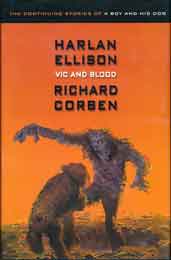

It took a few years, but V&B returned in VIC AND BLOOD: THE CONTINUING ADVENTURES OF A BOY AND HIS DOG, a two issue comic. Containing Richard Corben drafted adaptations of “A Boy and His Dog,” “Eggsucker” and “Run Spot, Run,” it was published by Mad Dog Comics in 1987-88, and in a collected edition in ‘89. The latter begins with a lengthy textual preamble detailing the events of World War IV, which “Broke out on the 215th anniversary of the birth of Edgar Allan Poe—19 January 2021,” and lasted five days, leaving the survivors “abandoned to the new masters of desolation: vicious roverpaks of parentless young boys…and their telepathic dogs.”

Corben’s artwork is done up in his inimitable style. This means all the characters, even the so-called adults, look like children, and there’s a definite lean toward the ghoulish (with shadows and darkness afforded great emphasis, and a description of the ghost of Quilla June given unforgettably macabre form). Other interesting elements include the underground town of “A Boy and His Dog” rendered in the form of an old west community, a close-up of Vic using a piece of Quilla June’s frilly dress as a tourniquet for the ailing Blood, and a depiction of the gang leader Fellini that somewhat resembles his real-life namesake.

A 2003 reissue of VIC AND BLOOD added a four page “Conversation That Took Place on a Wednesday Night.” Related yet again from Blood’s POV, this trifle has V&B conversing about death, complete with references to Lord Byron, Euripides and Samuel Johnson. Also included are the original textual versions of the stories that inspired Corben’s adaptations, and quotations from “THE WIT AND WISDOM OF BLOOD,” which includes morsels like “Don’t fret about it, kid; nobody gets out of childhood alive” and “In terms of labor relations, the basic problem with living your life is that it’s on-the-job training and by the time you get some skill at it, you’re permanently laid off.”

Vic and Blood’s final appearance (to date) was in the Subterranean Press hardcover compilation BLOOD’S A ROVER, published in 2018, the year of its author’s death (followed by expanded reprints from Edgeworks Abbey in 2019 and ‘21). It contained “Eggsucker,” “A Conversation…,” “Run Spot, Run” and the BLOOD’S A ROVER script, arranged in chronological order. The book is billed as the long-promised Vic and Blood “novel” Ellison never managed to complete, but despite some newly added passages connecting the stories together it doesn’t satisfy as a long-form narrative. The contents were clearly written at different points of their author’s life, with the relentlessness of A BOY AND HIS DOG at odds with the preachiness of BLOOD’S A ROVER, and the fact that the latter portion is in teleplay form marks it out from the rest of the book (Ellison and his publishers might as well have included portions of Richard Corben’s graphic adaptations, which would have made as much sense).

Still, I’m glad a grouping-together of the Vic and Blood stories exists. Obviously the saga’s creator is no longer with us to write the promised novel, so I’ll gladly settle for the next best thing.

See Also: HARLAN ELLISON AD 6; THE LAST DANGEROUS VISIONS: Anatomy of a Non-Publication