The late Harlan Ellison was something of an enigma. The man was renowned for his prolificacy (from Stephen King: “my own fecundity—however fecund that may be—pales beside Ellison’s, who has written at a ferocious clip”), but also widely knocked because, as one blogger wrote, “with any Harlan Ellison book, publication dates are best considered…fluid.” Yes, the man published over 1,800 stories and articles, but was also responsible for a great deal of incomplete and never-written assignments.

Included in that latter category is the screenplay for A BOY AND HIS DOG (1975), which Ellison, despite adapting his own 1969 novella, was unable to complete. His novel BLOOD’S A ROVER, an extension of the aforementioned BOY AND HIS DOG, likewise went incomplete (with its eventual publication consisting of four stories and a teleplay).

There was also a proposed short story called “Prey,” of which Ellison was only able to write a single page (followed by a twenty page explanation, contained in the 2013 collection HARLAN 101 (below), about why he was unable to finish it), and, most (in)famous of all, THE LAST DANGEROUS VISIONS.

The DANGEROUS VISIONS series began in 1967, in the seminal Ellison edited anthology of that title. Containing taboo-breaking, zeitgeist-spanning stories by virtually every major science fiction scribe of the day, paired with lengthy introductions by Ellison, DANGEROUS VISIONS was and remains one of the most iconic anthologies in sci fi history. Ellison followed it with AGAIN, DANGEROUS VISIONS in 1972, a longer (if less potent) volume with a fresh roster of contributors.

A third DANGEROUS VISIONS was inevitable. Its initial announcement was in the introduction to AGAIN, DANGEROUS VISIONS, with an anticipated publication of “approximately six months after this book.” Also promised was a new set of contributing writers that included Edward Bryant, Octavia Butler, Ian Watson, Michael Bishop, Frank Herbert, George Alec Effinger and John Christopher.

Yet the book, which initially clocked in at 445,250 words, continued to expand, with more stories acquired and the word count ballooning to a whopping 645,000 (WAR AND PEACE, by contrast, clocked in at 587,287 words). It inevitably grew out of the con trol of both its editor and its publishers, having been initially placed with Doubleday, followed by Harper & Row, Putnam and finally Houghton Mifflin. All the while Ellison continued to cling quite tenaciously to the stories of his 75 contributors (the initial count was 31), most of whom died before the book ever saw print—as, in 2018, did Ellison himself.

trol of both its editor and its publishers, having been initially placed with Doubleday, followed by Harper & Row, Putnam and finally Houghton Mifflin. All the while Ellison continued to cling quite tenaciously to the stories of his 75 contributors (the initial count was 31), most of whom died before the book ever saw print—as, in 2018, did Ellison himself.

The LAST DANGEROUS VISIONS saga has become a longstanding open joke in science fiction circles. According to the British novelist Christopher Priest, “even from Mr. Ellison’s first announcement many people suspected he would never deliver the book.” Yet Ellison, who suffered increasing health issues in his later years, never stopped promising the book would be completed, making (again according to Priest) continued “verbal claims about having finished and delivered LAST,” claims that were “invariably made in such an emphatic way, supported by plausible-seeming detail, that it (was) impossible to challenge them except by having to call Mr. Ellison a liar.”

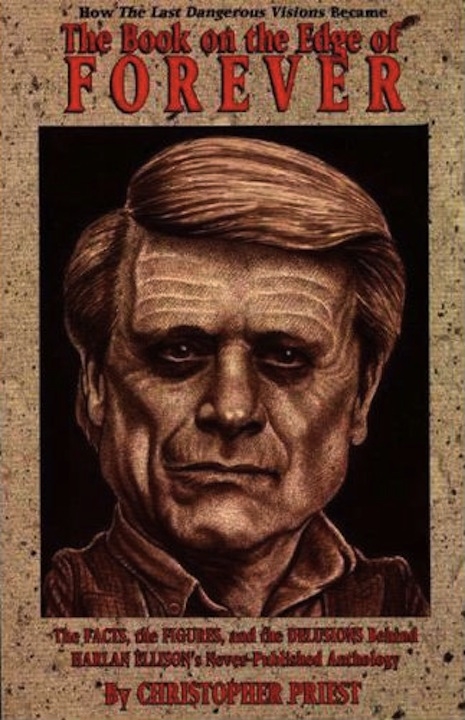

Priest did just that in his venomous 1987 essay “The Last Deadloss Visions.” The essay was later expanded to book form and published by Fantagraphics as THE BOOK ON THE EDGE OF FOREVER (below, a play on Ellison’s celebrated STAR TREK script “The City on the Edge of Forever”), which boasted a cover illustration by Drew Friedman and was nominated for a 1995 Hugo. The history behind this book is complex but I’ll get to that. For now, let’s concentrate on Priest’s writing and arguments, which are reasonably solid, if extremely churlish.

Priest recounts the history of THE LAST DANGEROUS VISIONS, reasoning that Ellison lost control of the project early on yet refused to give up on it due solely to his own famously egomaniacal personality. Myself, I don’t find the situation as grievous as Priest makes it out to be (cancellations and broken promises being quite common in the publishing industry), and nor do I believe Ellison was holding on to the stories for purely megalomaniacal reasons. It seems to me that his enthusiasm for the project was genuine, and his unyielding determination to see it through quite admirable (if unrealistic).

Priest recounts the history of THE LAST DANGEROUS VISIONS, reasoning that Ellison lost control of the project early on yet refused to give up on it due solely to his own famously egomaniacal personality. Myself, I don’t find the situation as grievous as Priest makes it out to be (cancellations and broken promises being quite common in the publishing industry), and nor do I believe Ellison was holding on to the stories for purely megalomaniacal reasons. It seems to me that his enthusiasm for the project was genuine, and his unyielding determination to see it through quite admirable (if unrealistic).

Also recounted in THE BOOK ON THE EDGE OF FOREVER is Priest’s own involvement in THE LAST DANGEROUS VISIONS. He claims Ellison asked him to submit a story, which Priest “reluctantly” broke off work on a novel to write, only to withdraw it a few years later, resulting in threats and denunciations from Ellison. It seems Priest’s history with Ellison might go a bit deeper than what he described, as indeed it did.

Illuminating that last point are two 1995 GAUNTLET magazine articles written by Richard Cusick. The first of them is “Bugfuck!” from issue #9, a near-40,000 word account of how Ellison tried to get THE BOOK ON THE EDGE OF FOREVER censored, and how Gary Groth, who runs Fantagraphics Press and COMICS JOURNAL, called Ellison out in the pages of the latter publication. Also involved was author Charles Platt, who pissed off Ellison on more than one occasion, and formed an organization called Victims of Ellison (or VOE). It was Platt who apparently shepherded the US publication of THE BOOK ON THE EDGE OF FOREVER, and who, according to Cusick, deliberately precipitated the censorship drama, together with Groth, by handing out copies of Priest’s tome at a convention where Ellison was speaking.

“Bugfuck!” is persuasively argued, but it’s an extremely long, torturously complicated piece that may be a bit too inclusive for its own good. It traces not just the history of THE BOOK ON THE EDGE OF FOREVER, but also the long-standing Harlan Ellison-Charles Platt feud (no surprise: there was a woman involved) and the VOE (which later became EOE, or “Enemies of Ellison”). The article is further crippled by its conclusion, in which Ellison is quoted on how “it is my hope and intention to do the work that remains on THE LAST DANGEROUS VISIONS in 1995.” As we all know, that didn’t happen.

Cusick took on THE BOOK ON THE EDGE OF FOREVER directly in issue #10 of GAUNTLET, in “The Book on the Edge of Reality.” Cusick criticizes Priest’s writing as poorly argued and personally biased (apparently Priest’s abovementioned claims about the story he wrote for THE LAST DANGEROUS VISIONS were inaccurate). As a diehard Ellison fan, I’m inclined to go along with Cusick’s arguments, but the fact remains that it’s been nearly thirty years since Priest’s tome appeared and THE LAST DANGEROUS VISIONS still has yet to be published. There has, however, been a mighty promising development.

personally biased (apparently Priest’s abovementioned claims about the story he wrote for THE LAST DANGEROUS VISIONS were inaccurate). As a diehard Ellison fan, I’m inclined to go along with Cusick’s arguments, but the fact remains that it’s been nearly thirty years since Priest’s tome appeared and THE LAST DANGEROUS VISIONS still has yet to be published. There has, however, been a mighty promising development.

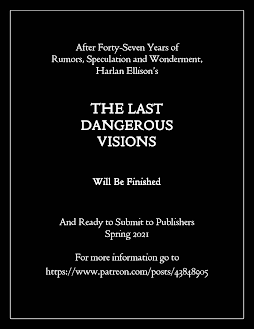

That development occurred in May 2022, when Ellison’s literary executor J. Michael Straczynski claimed THE LAST DANGEROUS VISIONS would finally see print on September 1, 2024, courtesy of Blackstone Publishers. My problems with this claim should be pretty obvious: aside from the fact that these now 50 year old stories are probably no longer as relevant as they once were (much less dangerous), I can’t help but feel a little skeptical of Straczynski’s promises, as they mirror those of Ellison, who was constantly assuring us that the book’s publication was imminent (Straczynski, for the record, has also promised to turn Ellison’s Sherman Oaks home into a museum, which has yet to occur). Still, I wish Straczynski and Blackstone luck in this endeavor, and solemnly promise that if this book ever sees print I, for one, will buy it.