DUNE by Frank Herbert is the world’s bestselling science fiction novel. Initially published in 1965, it was both a mainstream success and a counterculture/college campus sensation, and remains popular today. As a sustained piece of speculative imagination it’s deeply impressive, and nearly unprecedented (not to mention a mite dull). Plus its story—about a desert planet, riddled with giant sand worms, in the sights of a galactic federation because said planet is the source of a powder (or spice) that’s crucial to the functioning of the federation—contains any number of Earth-bound political allusions.

The novel sprung from an article Frank Herbert intended to write about the sand dunes of Florence, Oregon. That article was never completed, but its particulars were combined with Herbert’s experiences with Psilocybin and his interest in feudalism and messiahs (which, as Herbert observed, are especially prevalent in desert environs) to create DUNE.

It was the first in a series of “DUNEiverse” novels that came to consume Herbert in his later years, and were continued after his death by his son Brian and author Kevin J. Anderson. The most interesting of those novels was GOD EMPEROR OF DUNE (1981), the fourth in the series (preceded by DUNE MESSIAH and CHILDREN OF DUNE), in which Leto Atreides, the son of DUNE’S hero Paul Atreides, merges with a sand worm larvae to become a literal god who spends the book agonizing about how to properly unite humanity. Heady stuff, and one of many examples of aging science fiction writers turning, deliberately or not, to the odd and perverse in their final years (see also TO SAIL BEYOND THE SUNSET, the final novel by Robert A. Heinlein, which fixates quite creepily on mother-son incest).

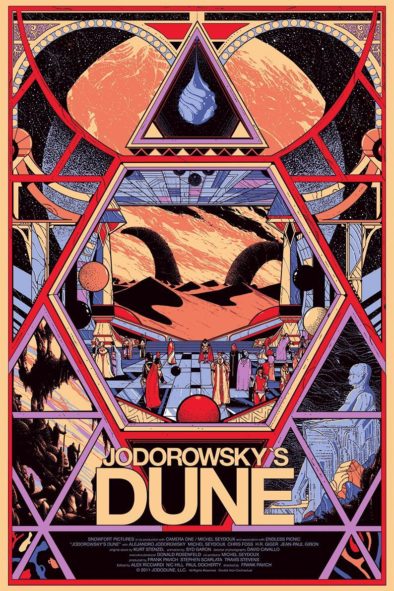

DUNE also inspired two high profile movie adaptations, the latest of which is set to be released on October 22, 2021. DUNE’s film history, in fact, began in 1969, when producer Arthur Jacobs optioned the book. Following Jacobs’ 1973 demise that option was snapped up by Alejandro Jodorowsky, the Chilean-born, Paris-based iconoclast who remains best known for the midnight movie legend EL TOPO. Among the cast and crew Jodorowsky assembled were Orson Welles, Salvador Dali, Jean “Moebius” Giraud, Dan O’Bannon, H.R. Giger and David Carradine.

Jodorowsky never seemed too jazzed about the novel, later stating that he was “raping Frank Herbert” (albeit “with love”) and creating a DUNE that was entirely his own. This ambitious project’s two-year pre-production, which was abandoned in late 1975, was the subject of the 2013 documentary JODOROWSKY’S DUNE.

JODOROWSKY’S DUNE (Trailer)

As directed by Frank Pavich, JODOROWSKY’S DUNE contains extensive interviews with an elderly Jodorowsky, who comes off as alternately enthusiastic and (understandably) bitter. Also provided are many eye-opening views of the conceptual art, and animated storyboards showing select scenes from the script (such as the universe-spanning opening shot) as they would have played out onscreen.

Pavich also makes it clear that Jodorowsky’s DUNE was deeply influential, with many of its crewmembers channeling their inspiration into subsequent projects. This is not unlike what occurred when another ambitious 1970s literary adaptation, John Boorman’s LORD OF THE RINGS, collapsed, leading Boorman to create the outrageous science fiction pastiche ZARDOZ (1974).

ZARDOZ (Trailer)

Featured in that irredeemably loony spectacle is Sean Connery as a man in a future era where the rich, who’ve been cowed by feminine power, live inside an invisible shield while everybody else fends for themselves in a land lorded over by a floating stone head. The film, utilizing every imaginable low-budget special effect, is extremely inventive, and also quite shameless, with Connery appearing in a wedding dress, condemned prisoners begging their executioners to kill them and a great deal of head-scratching psychedelia. It’s a film that to some is an interminable mess and others (here, here!) an insane tour de force. ZARDOZ, I’d opine, is also very close to how Jodorowsky’s DUNE would likely have played had that project made it to the screen.

Jodorowsky’s DUNE was responsible, in part, for ALIEN, into which the former film’s special effects designer Dan O’Bannon and conceptual artists H.R. Giger and Ron Cobb channeled their ideas, while Cobb also did design work on STAR WARS. That movie’s borrowings are well known: the FLASH GORDON serials, the Akira Kurosawa film THE HIDDEN FORTRESS and the French comic series VALERIAN AND LAURELINE. To that line-up we’ll have to add DUNE, which is directly referenced in the galactic ruling class that oversees the STAR WARS universe and the desert planet of the early scenes (upon which is seen a skeleton that is quite evidently that of a sand worm).

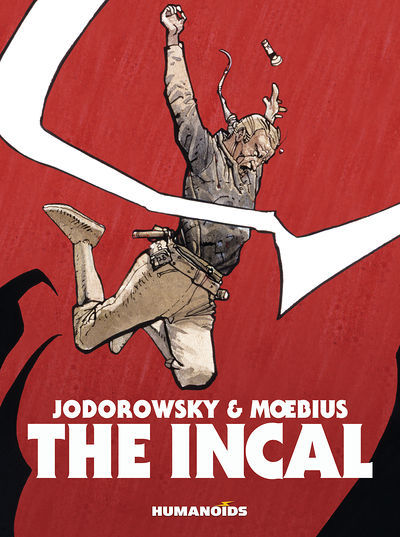

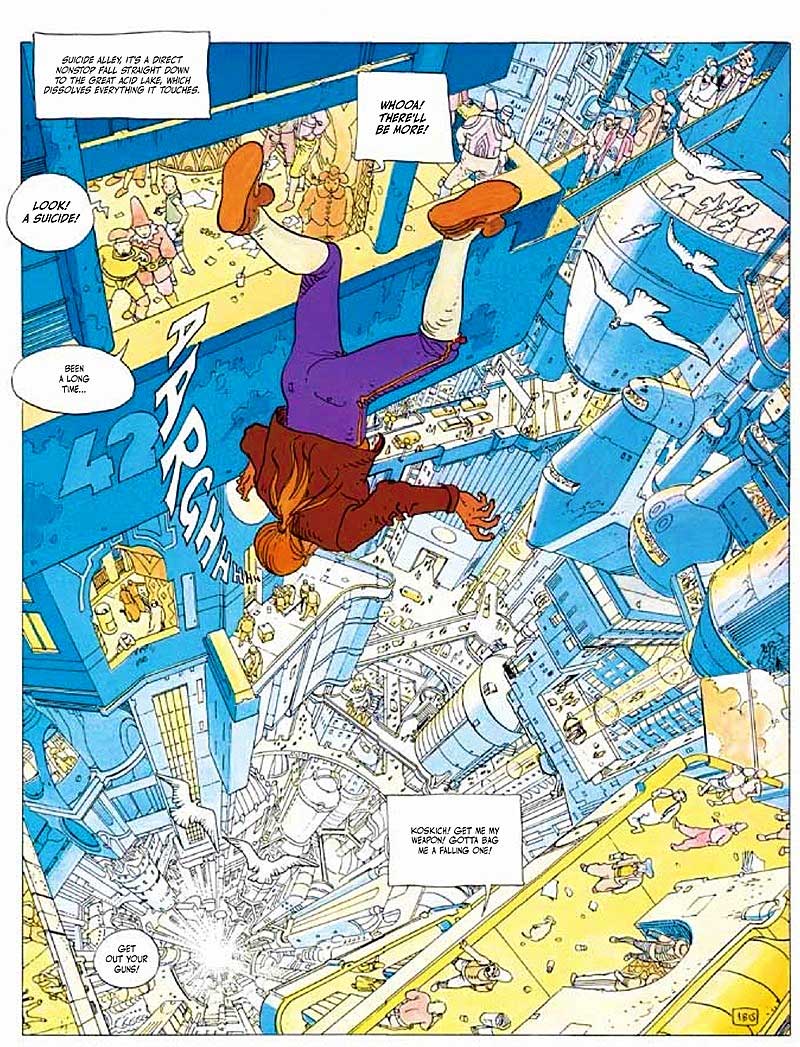

There was also THE INCAL, a French language science fiction comic scripted by Jodorowsky and illustrated another of his DUNE collaborators, Jean “Moebius” Giraud. With this project Jodorowsky and Moebius did precisely what John Boorman did with ZARDOZ, channeling the ideas for their unmade film project into a wholly original, and wholly mind-roasting, concoction, which begins with a man on the run and ends with the universe in peril. In between, we meet quite a few quirky characters, including John DiFool, a dweeb who holds the fate of the universe in his hands; the Berg Queen, who needs to be impregnated every thousand years in order to reseed the race; and the conjoined Emperoratrix, who float around in a massive egg. At the center of it all is the Incal, a Godlike entity in two parts that must be joined together if the human race is to survive “the Great Darkness.”

THE INCAL was released in English language versions that include a three-part series published by Epic in 1988, a 2005 two-parter from Humanoids/DC with digitally updated visuals (skip this one!) and a single volume from Humanoids in the 2010s (your best bet). It may be a bit wonky from a storytelling standpoint (not an uncommon criticism when it comes to Euro comics), but showcases Jodorowsky’s ceaseless imagination in rare form, which combined with Moebius’s incredibly rich artwork has produced a classic the likes of which has never been seen before or since. Much like DUNE, it spawned its own universe through numerous Jodorowsky-scripted spin-off comics that include BEFORE THE INCAL and THE METABARONS, but none in my view come close to capturing the insane brilliance of the initial INCAL.

Getting back to DUNE, for a time it seemed that it was destined to join the ranks of THE DEMOLISHED MAN, MORE THAN HUMAN and STRANGER IN A STRANGE LAND, iconic science fiction novels that have inspired film proposals as myriad as those of DUNE. That it was the one that ultimately got made is ironic, as out of those four books DUNE seems the least cinema-friendly. According to Harlan Ellison, who was at one point approached to write the screenplay, “this was a book so complex and vast in scope that it never could be made, for anything under a hundred million dollars.”

The DUNE movie’s inception began in 1978, when mega-producer Dino de Laurentiis snatched up the film rights. He initially commissioned Frank Herbert to adapt the novel himself, which resulted in a 175 page screenplay that was, by all accounts, “unworkable.” It was followed by an adaptation by TWO LANE BLACKTOP’S Rudy Wurlitzer that included an incestuous tryst between Paul Atreides and his mother Jessica that reportedly pissed off Herbert to no end (was Robert Heinlein involved?).

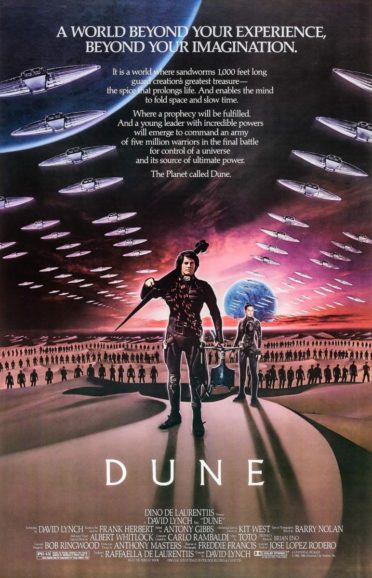

David Lynch was de Laurentiis’ next hire (Lynch told the press “You’ve got to be either stupid or crazy to try something like this”), and his efforts resulted in the first DUNE movie to hit the screen. Budgeted at around $40 million, we shouldn’t be surprised that the 1984 film was a legendary disaster that Lynch has subsequently disowned. Its story, crammed into 137 clunky minutes, was severely compressed from that of the novel, playing like more of a highlight reel than a proper narrative, with characters that barely register (there are far too many of them) and downright Ed Woodian, conviction-free performances.

DUNE (David Lynch) Trailer

The art direction, however, is quite striking, utilizing 19th Century costumes and architecture in place of the expected futuristic décor (making the film an early example of Steampunk). The music, surprisingly enough, is also quite strong; the surprise is that the score was by the pop band Toto, following a desperate search by Lynch, which according to the book THE MAKING OF DUNE involved him listening to albums by a myriad of avant-garde composers. That Toto was his ultimate choice seems odd, but the innovative score they turned out, which mixes classical and modern tuneage (with perfectly placed electric guitar riffs), is among the least dated of the film’s elements.

I’d say the same for the special effects, which look awful today just as they did 37 years ago (and so can’t be said to have dated). Yet those giant sand worms, created by Carlo Rambaldi, are impressive, registering as undoubtedly the coolest worms of any DUNE adaptation.

So Lynch’s DUNE isn’t all bad. It even has some high-profile defenders. Ellison called it “the GONE WITH THE WIND and BIRTH OF A NATION of science fiction films. Filled with ideas and art directed with a wonderful baroque look, DUNE is a complex symphony of mythic grandeur,” while Frank Herbert had this to say about the film: “It begins as DUNE begins, it ends as DUNE ends and I hear my dialogue throughout. How much more could a writer want? Even though I have my quibbles…I like it. Very much.”

Also released was a so-called “Director’s Cut” of Lynch’s film. In truth this cut, a poorly edited 176 minute slog that played on cable television (and was released on DVD in 2006), was an unauthorized version in which Lynch had no input outside of changing his credited name thusly: the screenwriter is rendered as “Judas Booth” and the director the ever-prolific “Alan Smithee.”

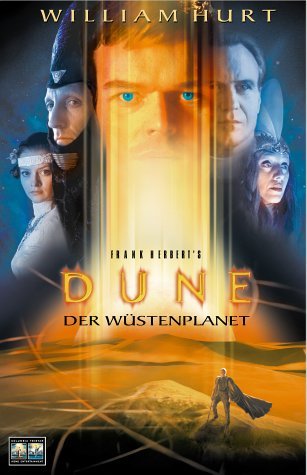

There followed the three part SyFy (or as it was known then, Sci Fi) Channel miniseries DUNE in 2000, which won two Emmys, and its sequel CHILDREN OF DUNE (2003). These series, the first of which was scripted and directed by TALES FROM THE DARKSIDE: THE MOVIE’s John Harrison, tend to be passed over in discussions of DUNE adaptations, and with good reason. Filmed on interior soundstages (even in “outdoor” scenes) with various distracting color filters and psychedelic interludes that seemingly aim to out-Lynch David Lynch, they were well-intentioned, but bring to mind Ellison’s crack about the impossibility of doing justice to DUNE for under $100 million, with SyFy’s budget evidently falling far short of that number.

DUNE Miniseries (SyFy) Trailer

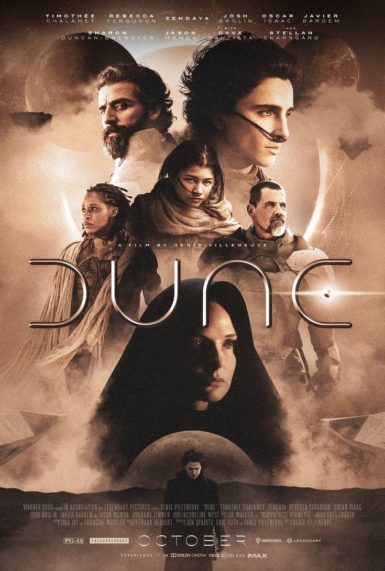

When considering the latest and supposedly definitive DUNE adaptation, that proposed $100 million budget was reached, and even surpassed: $165 million was its final price tag. It follows yet another failed attempt, this one from Paramount, who in 2008 hired Peter Berg and then TAKEN’S Pierre Morel to direct, only to abandon the project in 2011. Legendary Entertainment picked up the reigns in 2016, with the French Canadian Denis Villeneuve in the director’s chair.

Villeneuve, after making films such as POLYTECHNIQUE (2009) and SICARIO (2015), was known (according the imdb) for “Graphic and realistic depictions of violence,” yet has since revealed an affinity for science fiction. In this respect Villeneuve can said to be allied with his younger brother Martin, who pulled of an impressive feat with MARS AND APRIL (2012), in which a drama involving space travel, teleportation and the subconscious made manifest was pulled off for what his sibling’s Hollywood projects spent on catering.

Dennis Villeneuve’s own sci fi coronation occurred in 2016, with ARRIVAL, and continued into the next year, with BLADE RUNNER 2049. It was the latter, which wasn’t much of a success but did generate near-universal critical acclaim and two Academy Awards (things the original BLADE RUNNER failed to achieve), that gave Villeneuve the leverage to achieve his “lifelong dream” of filming DUNE.

Its production was, in keeping with the tenor of most everything DUNE-related, rocky. Filming was completed in July of 2019, with Villeneuve and his collaborators completely unaware that theirs was to be one of the final films of its type, which is to say a mega-budgeted Hollywood spectacle made expressly for the big screen. The Covid pandemic hit midway through post-production, forcing Villeneuve to complete the editing via zoom. There was also the decision by the film’s distributor Warner Bros. to do a simultaneous big and small screen release through HBO Max (due to the fact that Warners and HBO are both owned by AT&T). Villeneuve was quite vocal about his displeasure with the arrangement but it did no good, as that’s how his DUNE, after having its release date pushed back a year, was distributed.

Villeneuve has been careful in interviews to make the film seem relevant to contemporary audiences. He claims to have told screenwriters Jon Spaihts and Eric Roth to bring “more femininity” to the story than Frank Herbert and David Lynch did, and has made sure to point out that his DUNE is not a “white savior” narrative, even though, in the novel, it kind of is (with T.E. Lawrence, a.k.a. Lawrence of Arabia, being one of Herbert’s major inspirations). Did all this translate into a worthwhile film?

It did. Villeneuve’s two-part DUNE has been criticized for putting visual design before character development, but when you have visuals as impressive as those on display here is that really a drawback? Villeneuve also deserves credit for respecting his source material (especially in light of Apple TV’s FOUNDATION, which all-but discarded the Isaac Asimov stories it purported to adapt), resulting in a film whose first part mostly satisfies, with my major complaint being that it concludes on an unresolved note. DUNE PART II has a more epic sweep and increased pictoral splendor. I have problems, however, with Zendaya’s portrayal of Chani, the love interest of the Timothée Chalamet played Paul Atreides. Chani’s perpetually dour demeanor was apparently intended by Villeneuve as a critique of the novel’s militaristic arc, but the character comes off as a one-note sourpuss, so much so that I found the climactic suggestion of Paul’s intent to run off with the Florence Pugh essayed Princess Irulan a welcome development.

Villeneuve’s DUNE films were financially successful (although they got little Oscar attention), meaning further adaptations of Herbert’s saga are forthcoming. Good news? We’ll see.

DUNE (Villeneuve) Trailer