It’s a fact that South Africa isn’t exactly known for quality cinema. The “best” South African film, after all, is widely reputed to be Jamie Uys’ patronizing and nonsensical comedy THE GODS MUST BE CRAZY. With that in mind it’s hardly a surprise that when choosing worthwhile South African horror flicks the pickings tend to be slim—with at least two of the following films having been financed by sources outside South Africa—but quite strong nonetheless, with one authentic masterpiece among them.

Beyond that I’ll observe that one doesn’t have to look too hard to find political subtexts in these films, for reasons that will be obvious to anyone familiar with the turbulent history of South Africa in the late 20th Century.

Let’s start with the ultimate South African horror/cult film: Jans Rautenbach’s JANNIE TOTSIENS, a.k.a. FAREWELL JOHNNY, from 1970. To fully understand this bizarre film requires some knowledge of South Africa’s apartheid era of government-enforced racial segregation, which lasted from 1948 to 1991. Rautenbach’s previous film, 1969’s KATRINA, has been called the most controversial film ever made in South Africa due to its questioning of apartheid-instituted racism, and FAREWELL JOHNNY furthers those concerns, albeit in a more symbolic and abstract form.

Let’s start with the ultimate South African horror/cult film: Jans Rautenbach’s JANNIE TOTSIENS, a.k.a. FAREWELL JOHNNY, from 1970. To fully understand this bizarre film requires some knowledge of South Africa’s apartheid era of government-enforced racial segregation, which lasted from 1948 to 1991. Rautenbach’s previous film, 1969’s KATRINA, has been called the most controversial film ever made in South Africa due to its questioning of apartheid-instituted racism, and FAREWELL JOHNNY furthers those concerns, albeit in a more symbolic and abstract form.

It involves the catatonic college professor Johnny, who is brought by his parents to a strangely Gothic, cat-filled insane asylum. The inmates include a military man who thinks he’s still at war, a grown woman who behaves like a little girl, a black servant who serves as a receptacle for the inmates’ racism and a psychiatrist who is as nutty in his own way as his patients. What follows is a nightmare of confinement, thwarted love, punishment and suicide.

Highly fragmentary and episodic in nature, FAREWELL JOHNNY is anything but predictable. In place of a traditional three-act narrative Rautenbach lavishes copious amounts of screen time on individual characters, each of whom represents an aspect of South African society in the 1960s.

The proceedings are further marked by stark, noirish photography and art direction that rivals most movie haunted houses in its overtly gothic architecture. For good measure, a wealth of phallic balloons and creepy marionettes are also present, and generously displayed throughout.

Moving into the eighties, when anti-apartheid sentiment was steadily increasing, and even Hollywood was taking notice  (remember LETHAL WEAPON 2, whose villain was a pro-apartheid South African politician?), we find another asylum-set oddity: 1988’s THE SHADOWED MIND. Banned for several years in its native land, the film was heavily informed by FAREWELL JOHNNY but isn’t as strong overall, nor as overtly political.

(remember LETHAL WEAPON 2, whose villain was a pro-apartheid South African politician?), we find another asylum-set oddity: 1988’s THE SHADOWED MIND. Banned for several years in its native land, the film was heavily informed by FAREWELL JOHNNY but isn’t as strong overall, nor as overtly political.

The secluded insane asylum of THE SHADOWED MIND houses a woman with an irresistible compulsion to show her breasts, a suave ladies’ man with severe anti-social tendencies, a seductive nymphomaniac, a sexual exhibitionist and the asylum’s odd, and oddly sexual, woman director. Seduction is rife among the patients, as is murder, with a succession of brutal stabbings making life in the asylum even more unpleasant than it was to begin with.

Director Cedric Sundstrom’s visuals may not be on the level of those of FAREWELL JOHNNY, but they do feature some artful compositions and garish lighting that recalls Dario Argento. The murder scenes are surprisingly graphic, and the sex scenes plentiful but never especially erotic, lit as they are in ultra-gaudy eighties fashion. Worse, none of the actors deliver stand-out performances in a striking but only semi-successful film.

Next up is the British financed DUST DEVIL from 1992, a veritable epic of gore and magic from South African born writer-director Richard Stanley. It stars indie film darling Robert Burke as the title character, a shape-shifting mass murderer, together with THE LAST BOYSCOUT’S Chelsea Field as a restless young woman who has the misfortune to run into the Dust Devil in a desert wasteland. Political allusions abound, evident in Field’s callous treatment of the various black characters she encounters, and also the travails of a black police inspector (Zakes Mokai) investigating the Dust Devil’s killings.

Next up is the British financed DUST DEVIL from 1992, a veritable epic of gore and magic from South African born writer-director Richard Stanley. It stars indie film darling Robert Burke as the title character, a shape-shifting mass murderer, together with THE LAST BOYSCOUT’S Chelsea Field as a restless young woman who has the misfortune to run into the Dust Devil in a desert wasteland. Political allusions abound, evident in Field’s callous treatment of the various black characters she encounters, and also the travails of a black police inspector (Zakes Mokai) investigating the Dust Devil’s killings.

The production was reportedly quite calamitous, marred by the bankruptcy of its financier, England’s Palace Productions, and by a choppy 87 minute assemblage released on VHS by Miramax. Stanley subsequently put out a 104 minute directors cut in ‘94, and a 108 minute “final cut” that was released on DVD in 2006, and remains the preferred version.

What emerged from all the strife is an artful and compelling film unlike any other. It’s impressively rendered in bold, Sergio Leone-inspired visual compositions, with eerie sun baked locations redolent of myth and prophecy. Stanley shows a real feel for the deserts and wastelands of South Africa, which ultimately resonate far more than the cut-rate special effects and uneven performances.

THE GHOST AND THE DARKNESS (1996), a fact-based Hollywood production filmed in South Africa, isn’t on the same level  as the other films on this list, but its mixture of pulpy horror and prestige drama—as elucidated by screenwriter William Goldman, who pitched the project as “JAWS meets LAWRENCE OF ARABIA”—is quite inspired.

as the other films on this list, but its mixture of pulpy horror and prestige drama—as elucidated by screenwriter William Goldman, who pitched the project as “JAWS meets LAWRENCE OF ARABIA”—is quite inspired.

Set in the late 1800s, it features Val Kilmer as a British military engineer summoned to oversee the construction of a railroad in Kenya. The work is disrupted by a pair of man-eating lions, inspiring Kilmer to call in a fabled hunter, played by Michael Douglas, to help fight the critters. This lends an otherwise apolitical film a pointed racial subtext, with heroic white men tasked with protecting a dark-skinned populace too inept to do so themselves.

Director Stephen Hopkins, of A NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET 5 and PREDATOR 2, conveys a fair amount of old fashioned horror movie hysteria in the many ultra-tense night scenes of Kilmer and Douglas stalking the lions, which are vastly overlit but effective nonetheless.

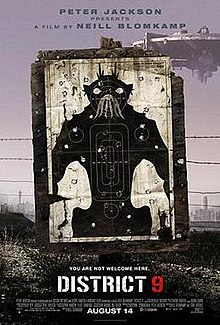

Finally we have the New Zealand/South African co-production DISTRICT 9, adapted from a well-received short (2005’s ALIVE IN JOBURG) by writer-director Neill Blomkamp and executive produced by Peter Jackson in 2009. Apartheid by that point had long since been abolished, but it’s explicitly recalled here, in what is very likely the most overtly political film on this list. In DISTRICT 9’s metaphoric universe a race of space aliens are confined to a small section of South Africa (inspired by the racial strife that occurred in Cape Town’s District Six during the apartheid era), where they’re persecuted by the human populace and used in horrific medical experiments.

Finally we have the New Zealand/South African co-production DISTRICT 9, adapted from a well-received short (2005’s ALIVE IN JOBURG) by writer-director Neill Blomkamp and executive produced by Peter Jackson in 2009. Apartheid by that point had long since been abolished, but it’s explicitly recalled here, in what is very likely the most overtly political film on this list. In DISTRICT 9’s metaphoric universe a race of space aliens are confined to a small section of South Africa (inspired by the racial strife that occurred in Cape Town’s District Six during the apartheid era), where they’re persecuted by the human populace and used in horrific medical experiments.

Blomkamp, who like Richard Stanley was born in South Africa, does a good job with the material, even though it—with its heavy-handed political drama, special effects-packed sci fi angle and action-intensive final third—presents challenges that would daunt most experienced filmmakers. Blomkamp doesn’t entirely pull it off, but I can’t say I didn’t enjoy the film, with its fast pacing, fun monster/transformation effects and memorably hysterical lead performance by Sharlto Copley, playing a government agent undergoing a scary transmutation.

What might we expect from future South African horror films? Not much, I’d wager, as the political realities that galvanized filmmakers like Jans Rautenbach and Richard Stanley have changed drastically in recent years. I’m glad apartheid is no longer in effect, but also recognize that since its repeal South Africa has become a far less interesting place.