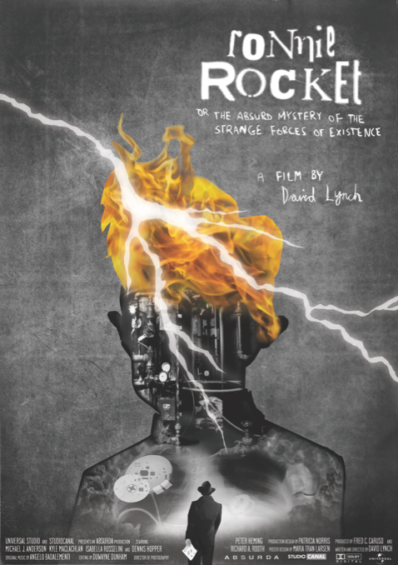

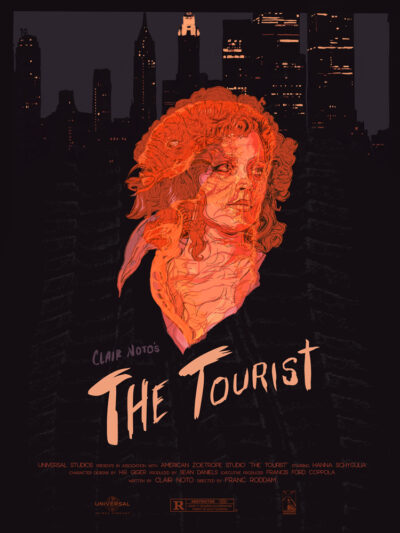

It’s been stated by many that if tantalizing film projects like H.G. Clouzot’s L’ENFER, Federico Fellini’s JOURNEY OF G. MASTORNA and Alejandro Jodorowsky’s DUNE had made it to production the resulting films would have assuredly “changed the face of cinema.” I tend to be skeptical about such pronouncements (as in truth there’s usually a reason films don’t get made, the above three in particular), but in the case of the iconic screenplays RONNIE ROCKET by David Lynch (below), INTERFACE by Charles Proser (below). and THE TOURIST by Clair Noto (below), I feel that had these scripts been filmed the face of cinema—science fiction cinema in particular—may indeed have been transformed irrevocably.

These three science fiction themed screenplays, written in the late seventies and early eighties (when John Sayles’ NIGHT SKIES and Harlan Ellison’s I, ROBOT debuted, proving that period was a fertile one for unmade sci fi cinema), are further linked by the fact that they all passed through the halls of the short-lived Zoetrope Studios (1980-84). An insanely ambitious creation of Francis Ford Coppola, Zoetrope was an artistically minded, auteur-friendly movie studio whose inception constituted, in the words of author Jon Lewis, “one of the boldest moves in the history of the movie business.” Yet as Lewis also notes, the early 1980s economy ensured that Coppola “could not have picked a worse time in the history of Hollywood to try to use his prestige as a motion picture director to take on the studio establishment.” Another obstacle was Coppola’s mega-budgeted ONE FROM THE HEART (1981), whose famously indulgent production ate up all of Zoetrope’s capital and, when it inevitably flopped, tanked the studio.

RONNIE ROCKET was written by David Lynch after the completion of ERASERHEAD. Lynch claims that Coppola circled the script—specifically, Coppola read it three times and then “wanted to lie down on a couch, close his eyes and have it read to him”—but never actually purchased it (not an entirely bad thing given what became of INTERFACE and THE TOURIST at Coppola’s hands). Lynch made further efforts to mount the production under the auspices of Mel Brooks and Dino de Laurentiis, but neither attempt came to fruition.

See more of Adam’s commentaries and reviews on David Lynch.

This “Absurd Mystery of the Strange Forces of Existence” is not a great script, but it is a great David Lynch script. This is to say that the only filmmaker alive (or dead) capable of doing it justice is David Lynch, a fact that holds true for nearly all Lynch’s screenplays. Even the Oscar nominated BLUE VELVET probably wouldn’t have worked had it been filmed by anyone not named David Lynch (imagine how the description “Dorothy doesn’t move fast enough so Frank dumps her whole purse out on the front seat and grabs the lipstick and a flashlight. He puts the lipstick heavy onto his lips” might have been interpreted by another director), so unless Lynch succeeds in mounting this long-in-development project at some point in the near future our chances of ever seeing a RONNIE ROCKET film are nil.

Involved is a “dark land where mysteries and confusions abound, where fear and terror fly together in troubled cities and absurdities.” A scumbag named Hank Bartells has reversed the flow of electricity, causing the lights to be turned off rather than on and spreading depression and physical malady through the land. A character identified only as “Detective” is attempting to ferret out Hank and stop his evil reign.

Dan and Bob are a pair of surgeons who snatch the horrifically deformed three foot corpse of one Ronald De Arte (meant to be played at one point by TWIN PEAKS’ Michael Anderson) and resurrect it FRANKENSTEIN-like with electricity (reversed electricity, presumably). Dan, Bob and their shared girlfriend Deborah turn Ronald into Ronnie Rocket, who wears an electrical appliance on his chest that has to be plugged in periodically and evinces a talent for belting out rock tunes. This results in Ronnie becoming a rock star, and the unlikely savior of this odd universe—which undergoes a rather profound transformation in the positively mind-roasting final pages, which take the material in an entirely different, and infinitely weirder, direction.

Another thing this script brings up is how dependent Lynch’s films are on actor-director collaborations. The character of Hank, for instance, seems to emerge from the dial-a-villain school of screenwriting, but I suspect that Lynch’s genius for casting would rectify that issue should this script ever be filmed, with the prospective actor elevating the part in the same way Dennis Hopper did his villain role in BLUE VELVET and Diane Ladd hers in WILD AT HEART. The female roles likewise tend to come off as one-dimensional (all are sex-mad breast bearing harlots), but that would likely be alleviated onscreen, as proven by the work of Lynch starlets like Isabella Rossellini, Laura Dern, Sheryl Lee and Naomi Watts.

INTERFACE by Charles Proser is the most formally inventive of the three scripts under review, being a rare example of a POV movie, with the whole thing visualized from a character’s subjective POV a la LADY IN THE LAKE (1946), ENTER THE VOID (2009) and HARDCORE HENRY (2015). Here the POV is that of a cybernetically enhanced individual with godlike powers; think of the sequence in ROBOCOP in which the title character comes to in a laboratory where he/we are surrounded by various subsidiary characters (from the Edward Neumeier/Michael Miner ROBOCOP script: “We’re inside a complex laboratory. TECHNICIANS hover around us. The world goes from black and white to color. “Are we locked in?” A technician peers in. SNAP! BLACK”), but stretched to 89 pages.

The INTERFACE script was a ten year labor of love (with the date of the draft I read being 1987) that was purchased in 1980 by Coppola–who then, after running short of funds during the production of ONE FROM THE HEART, sold it (without Proser’s consent) to Paramount for a million dollars. Paramount’s reaction to the script is summarized by an anecdote about how the studio’s then head of production Don Simpson, in his one and only meeting about INTERFACE, reportedly shouted “This studio is never going to make a POV movie! Never!,” to which Proser is said to have replied, “Fine! Give it back to me!”

That didn’t occur, as Paramount still owns the rights to INTERFACE and has no evident intention of giving them up. The script did at least lead to some lucrative writing assignments for Proser, including an extensive (if uncredited) rewrite on TOP GUN (1986) and the original draft of INNERSPACE (1987). Yet INTERFACE, a tight and focused feat of pure imagination with undeniable real world implications, remains Proser’s masterpiece.

Walt is a fighter pilot severely injured in a plane crash. He awakens to find he’s lost his body and that his brain has been interfaced to a computer system, with modules that allow for vision and speech. It’s not long before Walt learns how to use his computerized state to its utmost, tapping into security cameras to explore the world outside the laboratory (including, inevitably, “shots of nude and semi-nude girls relaxing in baths”), manning cars, reading peoples’ minds and having what may be the first-ever depiction of cybersex with an attractive scientist named Emily.

But trouble brews in the form of a shadowy other that may be a rival disembodied consciousness or a monster from Walt’s Id. There’s also the uncomfortable fact that, as gradually becomes clear, Walt is being groomed by his handlers to wage war, something he’s none too happy about, with his resentment growing increasingly virulent and dangerous.

The mind-reading aside, this is all disturbingly plausible, and more pertinent to today’s world than that of the 1980s. The concept of using security cameras to keep an eye on the world may have seemed far-fetched back then (with Walt simply ordering more cameras from the Office of Internal Security if there isn’t one already available) but makes perfect sense these days, as does computerized warfare and hacking, a term that didn’t exist in 1980 but is nonetheless utilized to its fullest by Walt.

On the downside, Proser appears to have attended the Shane Black school of distracting metafictional asides. An example of such occurs on page 45 of Black’s LETHAL WEAPON script, describing an “EXT. POSH BEVERLY HILLS HOME” as “The kind of house that I’ll buy if this movie is a huge hit.” A similar, albeit far more cynical, spirit is evident on page 65 of INTERFACE, which contains the following reader-addressed aside: “If your audience is so terrified of using their own brains for a moment, they probably don’t have the brains to come up with five dollars or the intelligence to find the movie theater” (a handwritten note scrawled in the margin of the copy I perused reads “¿What?”).

THE TOURIST hails from 1980, when its author Clair Noto was hired by Universal to write it. Inspired by THE DAY THE EARTH STOOD STILL (“The idea of a human being who wasn’t a human being had been in my mind for a long time”) and the films of “unstructured directors” like Fellini and Antonioni, Universal didn’t have much luck filming THE TOURIST. That was despite a volley of rewrites by a retinue that included Dan O’Bannon and Harlan Ellison, and conceptual art by H.R. Giger (which Noto claims “did not look like what I had imagined the aliens to look like…I think they had production designs made before they had a draft that they wanted to use”).

From there the script, after getting bounced by United Artists, was purchased by Francis Ford Coppola. The production (as we know) never went forward, with director Franc Roddam, who was on board to direct THE TOURIST, claiming Coppola “treated us like shit. It was appalling.” Further strife occurred when Noto and Roddam attempted (like Lynch) to get the project remounted with Dino de Laurentiis, only to have the deal held up by Coppola, who demanded a fee for the script, and Renee Missell, who penned several Universal-approved rewrites and claimed partial ownership. Thus THE TOURIST floundered, although it has proven fairly influential, being the alleged inspiration for MEN IN BLACK (1997).

Author Lee McGeorge, who penned an unauthorized novelization of THE TOURIST, has dubbed the script a “bit of a mess.” He’s not incorrect, as its story of an extraterrestrial slug creature, hailing “from a planet of information and erotica” who’s taken the form of a beautiful woman named Grace Ripley, is a bit of a hodgepodge. This woman spends most of the script dashing around New York City (she’s supposed to be a high-powered business executive yet is never seen doing any work), with motives that aren’t too clear. Also afoot are three male aliens who function as rivals and allies, and a non-alien woman named Spider who has definite designs on Grace and her non-human cohorts. Truly, there’s a reason this script was never filmed, yet there’s also a reason it’s endured for as long as it has.

The grotesque fascination exerted by THE TOURIST is positively transcendent. The descriptions of humanoid aliens attacking slug critters on an alien planet (“At first it looks like some kind of violent battle, then the motions become more and more like mating. The noise they make is erotic and longing”), the otherworldly dust swirls that occur whenever Grace has sex (“The dust has formed and is hardening. The cocoon is forming around them and is in quite an advanced stage”) and unholy transmutations to which she and her fellows are subject (“His body becomes a thick spongy mass that begins to separate into thousands of tiny, lima-bean shaped fragments that are each alive, and free-moving”) are profoundly haunting, and guaranteed to remain embedded in the reader’s consciousness long after the confused narrative has evaporated.