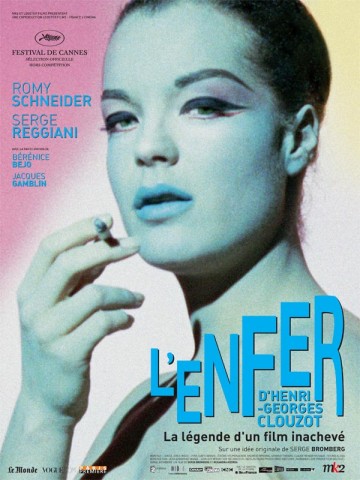

The fascination exerted by aborted film projects has reached a fever pitch in recent years, and a large part of the reason, I believe, was the partial reconstruction of Henri-Georges Clouzot’s L’ENFER/THE INFERNO in 2009. H.G. Clouzot (1907–1977) was one of France’s most successful directors, having scored international successes with THE WAGES OF FEAR/LE SALAIRE DE LA PEUR (1953) and DIABOLIQUE/LES DIABOLIQUES (1955). With 1964’s L’ENFER he sought to outdo himself in a film that, according to documentarian Serge Bromberg, was intended to “revolutionize cinema.”

The fascination exerted by aborted film projects has reached a fever pitch in recent years, and a large part of the reason, I believe, was the partial reconstruction of Henri-Georges Clouzot’s L’ENFER/THE INFERNO in 2009. H.G. Clouzot (1907–1977) was one of France’s most successful directors, having scored international successes with THE WAGES OF FEAR/LE SALAIRE DE LA PEUR (1953) and DIABOLIQUE/LES DIABOLIQUES (1955). With 1964’s L’ENFER he sought to outdo himself in a film that, according to documentarian Serge Bromberg, was intended to “revolutionize cinema.”

Clouzot’s conception, predicated on the belief that “no one had ever depicted jealousy properly,” involved a seemingly mild-mannered hotel owner (Serge Reggiani) driven mad by jealousy, with the object of his madness being his sexy wife, played by the Austrian born French movie superstar Romy Schneider (1938-1982), with whom Clouzot was admittedly obsessed. The film was backed by Columbia Pictures, who provided Clouzot with the most substantial budget he ever had, yet the production was shut down after a weeks, leaving behind a great deal of experimental test footage and a few dramatic scenes shot in France’s scenic Cantal Department.

The footage lay dormant for over forty years, until the 2009 appearance of HENRI-GEORGES CLOUZOT’S INFERNO/L’ENFER  D’HENRI-GEORGES CLOUZOT by Serge Bromberg and Ruxandra Medrea Annonier. It was a documentary on the unmaking of a film, and by no means the first. There was also Bill Duncalf’s THE EPIC THAT NEVER WAS from 1965, which documented the unfinished 1937 filming of I, CLAUDIUS. Duncalf’s film remains the template for such fare, featuring extensive interviews with many of the surviving principals, smooth narration by Dirk Bogarde and a wealth of surviving footage from the film. Another, even more famous unmaking-of documentary appeared in 2002, in the form of Keith Fulton and Louis Pepe’s LOST IN LA MANCHA, about Terry Gilliam’s aborted attempt at making THE MAN WHO KILLED DON QUIXOTE (which he eventually completed in 2019).

D’HENRI-GEORGES CLOUZOT by Serge Bromberg and Ruxandra Medrea Annonier. It was a documentary on the unmaking of a film, and by no means the first. There was also Bill Duncalf’s THE EPIC THAT NEVER WAS from 1965, which documented the unfinished 1937 filming of I, CLAUDIUS. Duncalf’s film remains the template for such fare, featuring extensive interviews with many of the surviving principals, smooth narration by Dirk Bogarde and a wealth of surviving footage from the film. Another, even more famous unmaking-of documentary appeared in 2002, in the form of Keith Fulton and Louis Pepe’s LOST IN LA MANCHA, about Terry Gilliam’s aborted attempt at making THE MAN WHO KILLED DON QUIXOTE (which he eventually completed in 2019).

In the case of HENRI-GEORGES CLOUZOT’S INFERNO we got both a reconstruction of its subject’s overriding narrative and a chronicle of its undoing. Bromberg had previously taken part (as an interviewee) in the 2004 doco SHIPWRECK NOTEBOOK/CARNET DE NAUFRAGE, which also concerned an aborted film shoot. The film in that case was a fictionalized expose of a penal colony for children by the revered Marcel Carne, who only managed to complete around twenty minutes of footage before the shoot was aborted in the summer of 1947. Unfortunately, SHIPWRECK NOTEBOOK’S makers Claudine Bourbigot and Elisabeth Feytit were unable to get ahold of any of that footage, leaving us with an interesting but unsatisfying collection of talking heads, vintage newspaper headlines and old photos.

HENRI-GEORGES CLOUZOT’S INFERNO, by contrast, contains a fair amount of the footage from the film it documents. Bromberg, after getting stuck in an elevator and striking up a friendship with Clouzot’s widow, was allowed to exhibit L’INFERNO’s surviving sound-free footage (culled from a reported 15 hours’ worth of celluloid), juxtaposed with newly shot scenes of actors  Bérénice Bejo and Jacques Gamblin reading the dialogue from Clouzot’s script and performing scenes that were never filmed. Also featured are extensive interviews with surviving crewmembers (including filmmaker Costa-Gavras, who labored as an assistant director on the film), who reveal that the production was chaotic and unfocused, with Clouzot lavishing a lot of time on footage that wasn’t in the script. The production was shut down after a myriad of problems, including the premature defection of its lead actor and a heart attack suffered by its director.

Bérénice Bejo and Jacques Gamblin reading the dialogue from Clouzot’s script and performing scenes that were never filmed. Also featured are extensive interviews with surviving crewmembers (including filmmaker Costa-Gavras, who labored as an assistant director on the film), who reveal that the production was chaotic and unfocused, with Clouzot lavishing a lot of time on footage that wasn’t in the script. The production was shut down after a myriad of problems, including the premature defection of its lead actor and a heart attack suffered by its director.

Based on what we’re shown, consisting of numerous experimental test shots (lensed in gaudy color) and a week’s worth of on-location photography (in black and white), L’ENFER could have ended up a terrifically innovative psycho thriller or a silly mass of psychedelic self-indulgence. Much of the footage, featuring Romy Schneider posing amid overtly psychedelic backdrops, directly recalls the film work of pioneering experimentalists like Marcel Duchamp and Fernand Léger while harkening forward to the psychedelia that took hold in the latter part of the sixties; in either case, alas, the imagery is quite dated.

In RERBERG AND TARKOVSKY: THE REVERSE SIDE OF STALKER/RERBERG I TARKOVSKIY. OBRATNAYA STORONA “STALKERA,” a documentary released the same year as HENRI-GEORGES CLOUZOT’S INFERNO, we’re given the lowdown on another aborted film project from a great director: the initial version of Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1979 STALKER (which was destroyed in a lab accident and ultimately reshot). Throughout, director Igor Maiboroda’s sympathies are with Georgi Rerberg, who photographed the discarded STALKER, with Tarkovsky assuming the bad guy role (note how the film’s score, comprised of classical compositions by Rerberg’s conductor father, always turns dark and ominous whenever Tarkovsky’s name is mentioned). HENRI-GEORGES CLOUZOT’S INFERNO likewise contains an antagonist, albeit one who also happens to be the protagonist: Clouzot himself, who much like his central character was drawn into an obsessive Hell of his own making, and took his film down with him.

The reasons for Clouzot’s issues have been speculated on at some length. Suggested culprits include Clouzot’s infatuation with Romy Schneider, the overabundance of freedom given him by Columbia and his declining health. All were probable contributors, but the most likely reason for Clouzet’s downfall, in my view, is that he never entirely got a handle on the conception of his film, a fact that appears evident in the overabundance of tests he insisted on shooting, and in two films that rose from the ashes of L’ENFER.

The first of those films was Clouzot’s own LA PRISONNIERE/WOMEN IN CAGES. Released in 1968, it’s an overwrought mess that all-but screams “Product of its time.” The really good parts occur in the beginning, when we see the outrageous art exhibits created by an avant-garde sculptor (Bernard Fresson), which include spinning plates, kaleidoscopic collages, mirror murals, etc. When the artist’s wife (Elisabeth Wiener) catches him making out with another woman she takes up with the eccentric gallery owner (Laurent Terzieff), who takes pervy photographs in his spare time. Ms. Wiener is gradually seduced into Terzieff’s world, with grave consequences for herself and the audience.

None of these characters are especially compelling, and neither is their three-way relationship. Clouzot, however, evidently  believed he’d created a profound depiction of female exploitation, which plays out in much the same way as L’ENFER’S depiction of male jealousy. A concluding dream sequence, featuring a wealth of insanely tripped-out imagery of the type Clouzot tried out in L’ENFER, is striking, but not nearly enough to save what, sadly, was to be Clouzet’s final feature.

believed he’d created a profound depiction of female exploitation, which plays out in much the same way as L’ENFER’S depiction of male jealousy. A concluding dream sequence, featuring a wealth of insanely tripped-out imagery of the type Clouzot tried out in L’ENFER, is striking, but not nearly enough to save what, sadly, was to be Clouzet’s final feature.

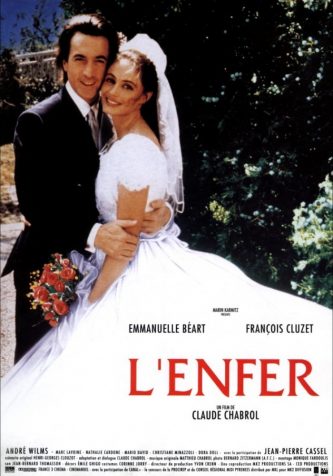

Onto the Claude Chabrol directed L’ENFER from 1994, which attempted to give the original film a modern-day makeover. Chabrol was often referred to as the “French Hitchcock,” which would appear to make him the ideal adaptor of this material, seeing as how Clouzot was previously given the same designation.

Chabrol’s film certainly isn’t the only example of a world-class director filming a script by a deceased forebear. In 1988 Lars von Trier pulled off a nifty filming of MEDEA, an adaptation of Euripides’s classic by the late Carl Theodor Dreyer, while the gifted Tom Tykwer made an extremely labored and unmemorable film from the late Krzysztof Kieslowski’s original screenplay for HEAVEN in 2002. Chabrol’s L’ENFER is, unfortunately, more in keeping with Tywer’s effort than it is with von Trier’s.

Chabrol did succeed, at least, in making the material his own. It can be said to form the middle part of a loosely-knit Chabrol trilogy bookended by THE CRY OF THE OWL/LE CRI DU HIBOU and THE BRIDESMAID/LE DEMESOILLE D’HONNEUR, films that center on insecure men destroyed by misplaced romantic yearnings. The difference between those films and L’ENFER is that they were adapted from skillfully wrought novels by Patricia Highsmith and Ruth Rendell, whereas L’ENFER had to make do with Clouzot’s rather clunky script, which without the psychedelic visuals of the 1964 version is painfully thin.

Yes, Chabrol removed the hallucinatory angle that was apparently so integral to Clouzot’s film, in favor of a more-or-less  straightforward account whose naturalistic veneer all-but begs us to question the reality of what we’re seeing. Another problem is with the main character, who, as played by François Clouzot, is neither interesting nor sympathetic. Most of Chabrol’s late period films were woman-centered, suggesting that he’d lost interest in male protagonists; that surmise would appear to be bolstered by L’ENFER, which contains a strong female lead. Emmanuel Béart plays the Romy Schneider role, ideal casting because Béart was to French cinema in the nineties what Schneider was in the sixties, and also because Béart has claimed she was inspired to get into acting after viewing Schneider’s work (in 1976’s MADO).

straightforward account whose naturalistic veneer all-but begs us to question the reality of what we’re seeing. Another problem is with the main character, who, as played by François Clouzot, is neither interesting nor sympathetic. Most of Chabrol’s late period films were woman-centered, suggesting that he’d lost interest in male protagonists; that surmise would appear to be bolstered by L’ENFER, which contains a strong female lead. Emmanuel Béart plays the Romy Schneider role, ideal casting because Béart was to French cinema in the nineties what Schneider was in the sixties, and also because Béart has claimed she was inspired to get into acting after viewing Schneider’s work (in 1976’s MADO).

In IT’S ALL TRUE (1993), directed by Bill Krohn, Richard Wilson and Myron Meisel, we were given the facts on Orson Welles’s long unseen three-part documentary on Brazil, made (and aborted) during the post-production of THE MAGNIFICENT AMBERSONS. Much of the footage Welles shot, unveiled by Wilson and Meisel, is striking, but the three-part opus that forms the core of IT’S ALL TRUE frankly doesn’t seem too impressive. This may be the ultimate takeaway from the L’ENFER saga: that portions of a film can’t be expected to speak for the whole, and maybe it’s better that whole doesn’t exist.