The death of Swiss artist Hans Rüdi Giger on May 12, 2014 was an incalculable loss to the horror field, the art world and all lovers of the fantastique. I don’t believe I’m exaggerating in calling H.R. Giger one of the great artists of his time, a man whose vision has impacted our world indelibly.

The death of Swiss artist Hans Rüdi Giger on May 12, 2014 was an incalculable loss to the horror field, the art world and all lovers of the fantastique. I don’t believe I’m exaggerating in calling H.R. Giger one of the great artists of his time, a man whose vision has impacted our world indelibly.

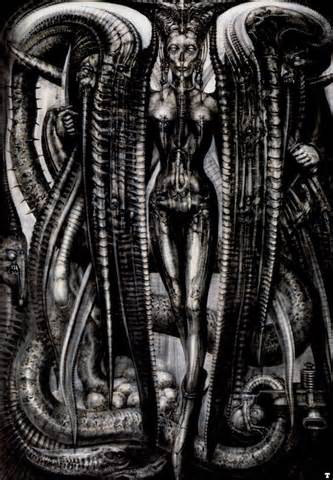

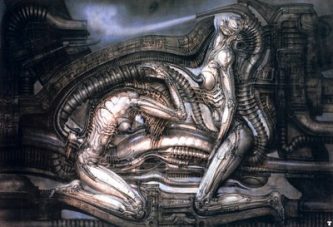

Giger’s paintings, created largely by airbrushing on specially created waterproof paper, all evince an unwavering commitment to his own peculiar vision. You’ll have a difficult time finding any unused space in Giger’s compositions—he claimed that when painting, “I am so disturbed by the white surface in front of me that I have to work continually until everything is covered,”—which are nothing if not densely detailed and obsessive. “I am driven on by my obsessions,” he once confessed, “by the pleasure of successfully accomplishing a particular detail…or simply the possibility of visualizing personal tensions, anxieties and problems and freeing myself of them.” Not surprisingly, Giger is said to have suffered horrific nightmares throughout much of his life.

Giger’s influences included Salvador Dali and H.P. Lovecraft (it’s not for nothing that Giger’s first book was entitled NECRONOMICON), and Giger’s art can be said to rank with the finest work of both. His horrifically beautiful imagery, visualized more often than not in hazy grayish illumination, tends to depict tortured humanoid figures melding with nightmarish biomechanical landscapes packed with disembodied mouths, bones, swords, teeth, worms and all manner of horrific—and horrifically sexual—ephemera. “Biomechanoids” was Giger’s term for the technology-infected beings of his art, which provided a dark foreshadowing of today’s increasingly mechanized reality.

Giger’s influences included Salvador Dali and H.P. Lovecraft (it’s not for nothing that Giger’s first book was entitled NECRONOMICON), and Giger’s art can be said to rank with the finest work of both. His horrifically beautiful imagery, visualized more often than not in hazy grayish illumination, tends to depict tortured humanoid figures melding with nightmarish biomechanical landscapes packed with disembodied mouths, bones, swords, teeth, worms and all manner of horrific—and horrifically sexual—ephemera. “Biomechanoids” was Giger’s term for the technology-infected beings of his art, which provided a dark foreshadowing of today’s increasingly mechanized reality.

Perhaps this explains why Giger’s art feels so oddly familiar and (even though his most famous works were done back in the 1970s and 80s) contemporary. I predict that it won’t be long before H.R. Giger’s paintings come to look less like surrealism and more like semi-documentary depictions of reality—which some would say they already do.

With that in mind, it makes sense that in his lifetime Giger achieved something few other avant-garde painters can claim: he breached the mainstream. His design work on ALIEN, which I’d argue was a central component in that film’s success, resulted in an Academy Award, and rendered Giger’s work as influential in movie land as it was in the art world (see the article “Hollywood rips off H.R. Giger” in the May 1988 issue of CINEFANTASTIQUE).

With that in mind, it makes sense that in his lifetime Giger achieved something few other avant-garde painters can claim: he breached the mainstream. His design work on ALIEN, which I’d argue was a central component in that film’s success, resulted in an Academy Award, and rendered Giger’s work as influential in movie land as it was in the art world (see the article “Hollywood rips off H.R. Giger” in the May 1988 issue of CINEFANTASTIQUE).

Of course Giger’s ALIEN designs became something of an albatross over the years, overshadowing if not entirely eclipsing his many other accomplishments. Just check out the obituaries that have appeared, nearly all of which identify him as the “ALIEN artist.” I can assure you he was a lot more than that, and that his non-ALIEN affiliated work has had far more resonance. (That’s despite an online claim that in recent years Giger “pretty much disappeared to everyone except the Goths and metalheads raiding his back catalogue for tattoos”—wrong.)

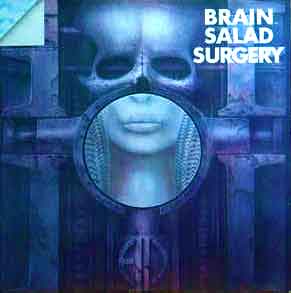

Especially noteworthy Giger achievements include his design work on Alejandro Jodorowsky’s unmade 1970s version of DUNE, as well as POLTERGEIST II (the original designs for which were toned down considerably in the finished film), SPECIES (an experience Giger summed up with “Oh that was wrong”), KILLER CONDOM and TOKYO: THE LAST MEGALOPOLIS. There are also his iconic album covers, for Emerson Lake & Palmer’s BRAIN SALAD SURGERY (a must-own in its original LP form), Debbie Harry’s KOO KOO and Danzig’s HOW THE GODS KILL, which furthered Giger’s mainstream credentials.

Giger’s “Necronom” series of paintings are especially fascinating creations with their depictions of a wide-headed creature that directly inspired the titular ALIEN. The “Passage” series consists of Giger-ized depictions of the “mechanically erotic” opening slot of a German refuse tank that portray said slot as an anus, a vagina and several even more bizarre permutations. Then there’s Giger’s iconic “N.Y. City” series (showcased in the 1981 large format paperback H.R. GIGER N.Y. CITY), which may well constitute his finest work with its astounding depictions of big city architecture infected by insectoid monsters, eroticized mechanical contraptions and a woman’s naked torso.

See also Giger’s depiction of robotic beings engaged in a bizarre form of mechanical eroticism in 1981’s “Erotomechanics VII”; the unearthly waterfall of 1977’s “Cataract,” with water that turns into machine-like tendrils; the gravity-defying black mass of 1974’s “Spell II” that involves a vampiric robot-woman with a massive penis-sprouting headdress, floating beakers with tortured baby faces and a table inlaid with industrial tubing and sharp knives; and the alien face poster art for the eighties cheese-fest FUTURE-KILL, an image that’s profoundly striking (and also a definite case of false advertising).

See also Giger’s depiction of robotic beings engaged in a bizarre form of mechanical eroticism in 1981’s “Erotomechanics VII”; the unearthly waterfall of 1977’s “Cataract,” with water that turns into machine-like tendrils; the gravity-defying black mass of 1974’s “Spell II” that involves a vampiric robot-woman with a massive penis-sprouting headdress, floating beakers with tortured baby faces and a table inlaid with industrial tubing and sharp knives; and the alien face poster art for the eighties cheese-fest FUTURE-KILL, an image that’s profoundly striking (and also a definite case of false advertising).

Today the majority of Giger’s artwork is housed in the H.R. Giger Museum (formerly the Chateau St. Germain) in Gruyeres, Switzerland. You might say, however, that its true residence is inside our minds, where these gorgeous and disturbing images are due bound to remain lodged, unvarnished and unforgettable.