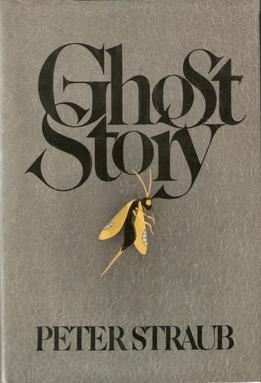

If you’re a reader of horror fiction the chances are better-than-average that you’re at least partially familiar with the writings of Peter Straub. One of the major scribes of the 1970s and 80s horror boom, Straub was best known for the 1979 bestseller GHOST STORY. Following an attempt at mainstream fiction (MARRIAGES) and two solid-but-unremarkable horror novels (JULIA and IF YOU COULD SEE ME NOW), GHOST STORY is often credited with elevating scare fiction from paperback fodder to high literature. It also established what would become Straub’s literary trademark: an unabashedly literary yet entertaining style that married high and lowbrow sensibilities.

If you’re a reader of horror fiction the chances are better-than-average that you’re at least partially familiar with the writings of Peter Straub. One of the major scribes of the 1970s and 80s horror boom, Straub was best known for the 1979 bestseller GHOST STORY. Following an attempt at mainstream fiction (MARRIAGES) and two solid-but-unremarkable horror novels (JULIA and IF YOU COULD SEE ME NOW), GHOST STORY is often credited with elevating scare fiction from paperback fodder to high literature. It also established what would become Straub’s literary trademark: an unabashedly literary yet entertaining style that married high and lowbrow sensibilities.

It also established what would become Straub’s literary trademark: an unabashedly literary yet entertaining style that married high and low brow sensibilities.

Over the course of the book we meet several different women who aren’t what they appear, and are indeed parts of the same entity, who despite having been killed years ago by a group of men keeps coming back. Years later this group, now codgers, deal with their crime in the form of scary stories they tell each other, but of course there is a very real ghost intent on killing them off.

In truth I’ve always found GHOST STORY overrated. As Straub himself admitted, it’s essentially Arthur Machen’s 1894 Anglo centric novella THE GREAT GOD PAN, replanted to the American northeast and stretched to an unwieldy 500-plus pages. GHOST STORY did, however, establish an aesthetic that would inform most of Straub’s later novels, being an extremely complex account that weaves in several different plot strands and concludes in an extended hallucinatory showdown. The latter portion, alas, drags on too long, and pales in light of the author’s following book.

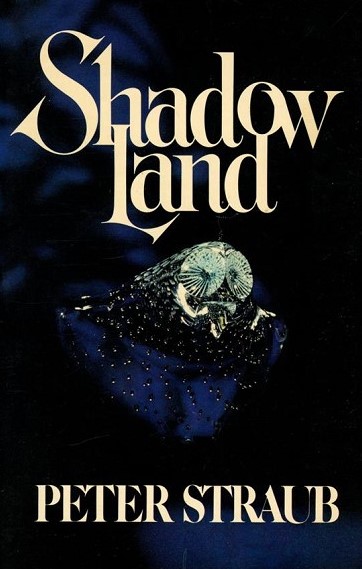

SHADOWLAND (1980) is in my view Straub’s masterpiece. It’s another highly expansive supernatural epic, but with a fairy tale inspired, time-tripping canvas that’s far more accommodating to its author’s sensibilities. Centering on Tom Flanagan, a young man who befriends a budding magician named Del at a horrific Arizona boarding school, it’s set largely in Shadowland, a Vermont mansion where Del’s uncle lords over a mini-kingdom of magic and nightmare, leading to a completely wild mélange of illusion, shape shifting, telepathy, astral projection and a crucifixion. Straub’s claim that “SHADOWLAND is close to horror, but it’s really a territory I created” might seem egocentric, but it happens to be correct, as SHADOWLAND is one of the few truly original genre novels to appear in the 1980s (some rather blatant lifts from THE MAGUS aside).

Things changed after the 1983 publication of the unabashedly excessive FLOATING DRAGON, in which Straub admitted “I tried to do everything I could think of.” He vowed to leave the horror genre behind (which didn’t last), but not before collaborating with Stephen King on what was to be Straub’s biggest-ever bestseller: 1984’s THE TALISMAN.

think of.” He vowed to leave the horror genre behind (which didn’t last), but not before collaborating with Stephen King on what was to be Straub’s biggest-ever bestseller: 1984’s THE TALISMAN.

It’s impossible to discuss Peter Straub without bringing up his longtime friend and collaborator Stephen K. The two made a good pairing, with Straub serving as the more refined yang to Stephen King’s beer drinking ying. King, who dubs himself “the literary equivalent of a Big Mac and fries,” stands in stark contrast to Straub, who (according to King) “brought a poet’s sensibility to the field, creating a synthesis of horror and beauty.”

…Straub, who (according to King) “brought a poet’s sensibility to the field, creating a synthesis of horror and beauty.”

The 700-plus page TALISMAN, alas, wasn’t quite the world-shaking synthesis it was cracked up to be. About a boy’s horrific journey across America, in which he divides his time between our world and an alternate universe called The Territories in order to save the life of his mother (the queen of The Territories), the novel is absorbing but overwrought, with some downright terrible writing unworthy of either scribe.

Straub’s contributions are most evident in a bit where Richard’s boarding school gets sucked into a nightmare that’s right out of SHADOWLAND (as is the oft-repeated sentence “When we all lived in California and no place else,” which mirrors SHADOWLAND’s mantra “When we all lived in the forest and no place else”). It lacks the transcendent excellence of the earlier novel, however, being the product of a collaboration between two like-minded but ultimately very different writers (King and Straub followed the novel up with 2001’s BLACK HOUSE, which I skipped).

It took another three years for Straub to turn out another solo novel, the Vietnam thriller KOKO. It purported to be a departure from the scary business, although a more accurate claim would be that it was a departure from the supernatural business, because it utilizes the quasi-literary template set by GHOST STORY, down to the phantasmagoric climax.

From there Straub turned out several more ostensibly mainstream thrillers: MYSTERY, THE THROAT, THE HELLFIRE CLUB and MR. X. I admittedly tuned out for those books, but was there for 2003’s LOST BOY LOST GIRL, a spirited return to the supernatural (and a rare Straub novel that clocks in under 300 pages). Comprised of a pell-mell collection of vignettes told from the vantage points of several different characters, the novel is often downright baffling, yet Straub somehow manages to weave an account that’s foreboding, mysterious and, finally, quite touching.

From there Straub turned out several more ostensibly mainstream thrillers: MYSTERY, THE THROAT, THE HELLFIRE CLUB and MR. X. I admittedly tuned out for those books, but was there for 2003’s LOST BOY LOST GIRL, a spirited return to the supernatural (and a rare Straub novel that clocks in under 300 pages). Comprised of a pell-mell collection of vignettes told from the vantage points of several different characters, the novel is often downright baffling, yet Straub somehow manages to weave an account that’s foreboding, mysterious and, finally, quite touching.

Straub’s final novel was A DARK MATTER from 2010. Described as the “ROSHOMON of horror novels,” it certainly sounds promising, but I’ve never been able to get into it.

I did, however, appreciate the many novellas with which Straub has interspaced his long-form publications. Those novellas include THE GENERAL’S WIFE (1982), a powerful account of supernatural frisson marred only by the fact that it’s a little too similar in conception and execution to Carlos Fuentes’ AURA; MRS. GOD (1990), a Robert Aickman inspired mind-boggler that exists in two different versions (one of them novel length); PORK PIE HAT (1999), which unites Straub’s passions for horror fiction and jazz; and THE BUFFALO HUNTER (1990/2012), a wholly odd account that added a new element to Straub’s literary retinue: humor, of the most opaque and unpredictable sort.

In conclusion, I’ll mention another Straub publication from 2010, his final year of activity: THE GREEN WOMAN, a Vertigo published graphic novel. Pivoting on Fielding Bandolier, the fearsome serial killer of Straub’s “Blue Rose” trilogy of novels (KOKO, MYSTERY and THE THROAT), the book, co-scripted by Michael Easton and illustrated by John Bolton, is a fractured, visually oriented yarn with much impossible-to-forget imagery and an unflinching exploration of the depths of madness and evil. I may have some issues with Straub, but he certainly finished out his career with a bang.

See Also Pork Pie Hat