2025 marked the 40th anniversary of one of the most unlikely success stories of the 1980s: PEE-WEE’S BIG ADVENTURE. An unabashed vanity project by the late actor/comedian Paul Reubens (1952-2023), the film was conceived as an independent film that, according to Reubens’ MIDNIGHT MADNESS (1980) co-star Eddie Deezen, was intended to be financed by Reubens’ parents. As it happened, the proposed film ended up getting a semi-glossy treatment, courtesy of Warner Bros. (who were confident enough in the finished film that it was made one the summer’s major tentpoles) and a young Tim Burton.

2025 marked the 40th anniversary of one of the most unlikely success stories of the 1980s: PEE-WEE’S BIG ADVENTURE. An unabashed vanity project by the late actor/comedian Paul Reubens (1952-2023), the film was conceived as an independent film that, according to Reubens’ MIDNIGHT MADNESS (1980) co-star Eddie Deezen, was intended to be financed by Reubens’ parents. As it happened, the proposed film ended up getting a semi-glossy treatment, courtesy of Warner Bros. (who were confident enough in the finished film that it was made one the summer’s major tentpoles) and a young Tim Burton.

PEE-WEE’S BIG ADVENTURE is a movie that exists in a subcategory of its own, being a kiddie comedy that’s also for grown-ups, headlined by a remote and quite probably insane protagonist. The only way this material could possibly work would be through the vision of a great director, and PEE-WEE’S BIG ADVENTURE, luckily, had one.

Tim Burton in 1985 was known as a Disney-employed animator and helmer of short films like VINCENT (1982), HANSEL AND GRETEL (1983) and FRANKENWEENIE (1984). He proved himself up to the task of making sense of PEE-WEE’S BIG ADVENTURE, as under Burton’s guidance Reubens created, in his characterization of child-man Pee-wee Herman, one of the screen’s most endearingly nutty personages. He lives in a cartoon universe in which employment and finances don’t exist, with Burton’s ingenious and imaginative visual design imparting a Fellini-esque carnival of toys, clowns and cute animals, visualized in the gaudiest imaginable colors.

The narrative, involving Pee-Wee’s search for his stolen bicycle (a premise inspired by Vittorio de Sica’s 1948 neorealist classic THE BICYCLE THIEF), matches the visuals in flamboyant invention. Included are a handful of excellent supporting turns, the most memorable of them delivered by the late Jan Hooks (1957-2014) and Alice Nunn (1927-1988) as, respectively, Tina the annoying tour guide and Large Marge, whose eyeball popping appearance is so iconic Burton has tried to recapture it in several of his subsequent films.

Another debuting talent was Oingo Boingo headliner turned musician Danny Elfman. This was Elfman’s first time out as a film composer, and it remains one of his finest hours, perfectly capturing the whimsical mood of the flick while quoting from the work of Nino Rota and Bernard Hermann.

The film’s sui generis brilliance is evidenced by Reubens’ subsequent non-Tim Burton helmed Pee-Wee outings BIG TOP PEE-WEE (1988) and PEE-WEE’S BIG HOLIDAY (2016), which didn’t have a shred of the distinction of PEE-WEE’S BIG ADVENTURE (regarding the TV show PEE-WEE’S PLAYHOUSE, I’d call it a conditional success). It was, however, not entirely without precedent.

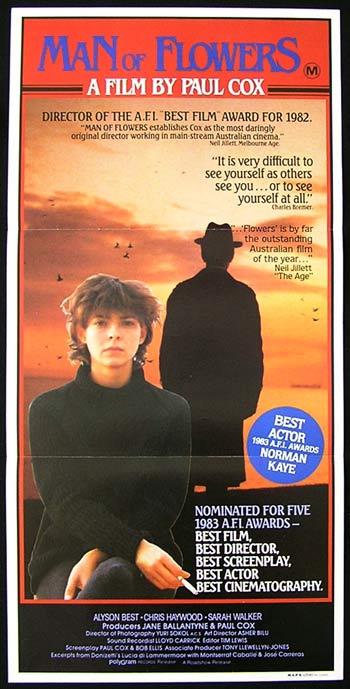

The Australian MAN OF FLOWERS appeared back in 1983. It was a visually extravagant art film from a director, the late Paul Cox (1940-2016), who was every bit as gifted and eccentric as Tim Burton. The film furthermore contained a lead actor, the late Norman Kaye (1927-2007), who was very Paul Reubens-like in his utterly distinct line readings and mannerisms. The character he plays, a middle-aged recluse named Charles Brenner, is, like Pee-Wee Herman, a highly eccentric fellow who appears to exist in his own hemisphere.

Chuck lives alone, surrounded by carefully tended flower gardens and a staggering collection of objects d’art. Having inherited his deceased mother’s vast fortune, he’s free to indulge his passions to the fullest in a carefree Pee-Wee-like existence. His activities include hiring an attractive young model (Alyson Best), to strip to the aural accompaniment of classical operas, but Charles is careful to keep his distance from her. In his mind he can look at a beautiful woman but can’t touch her (a dynamic that’s not dissimilar to Pee-Wee’s halting relationship with PEE-WEE’S BIG ADVENTURE’s Elizabeth Daily played lead actress).

Chuck lives alone, surrounded by carefully tended flower gardens and a staggering collection of objects d’art. Having inherited his deceased mother’s vast fortune, he’s free to indulge his passions to the fullest in a carefree Pee-Wee-like existence. His activities include hiring an attractive young model (Alyson Best), to strip to the aural accompaniment of classical operas, but Charles is careful to keep his distance from her. In his mind he can look at a beautiful woman but can’t touch her (a dynamic that’s not dissimilar to Pee-Wee’s halting relationship with PEE-WEE’S BIG ADVENTURE’s Elizabeth Daily played lead actress).

As with Pee-Wee, a host of equally eccentric characters orbit Charles. There’s a nutty postman (Barry Dickens), an insecure psychiatrist (Bob Ellis) and a no-talent artist (Chris Haywood) who makes the mistake of breaching Charles’ closely guarded sanctum. Werner Herzog also turns up as Chuck’s abusive father, in flashbacks that reveal the twisted origins of Charles’ eccentricities (something PEE-WEE’S BIG ADVENTURE never made clear).

This could have been grating if done in a conventional manner, but Cox, like Burton, creates a hermetic universe that’s entirely his own. The editing has a languid rhythm that I don’t think has been equaled in any other movie; it moves very slowly, approximating its protagonist’s aesthetic orientation, but remains compelling from start to finish. It is, in other words, a complete original.

I don’t believe MAN OF FLOWERS is in any way “better” than PEE-WEE’S BIG ADVENTURE; there’s a reason the former film didn’t get the type of 40-year anniversary celebration the latter is currently enjoying. Yet MAN OF FLOWER remains a haunting companion-piece to Reubens and Burton’s classic, which did with comedy what Cox and Kaye accomplished with heartfelt aestheticism.