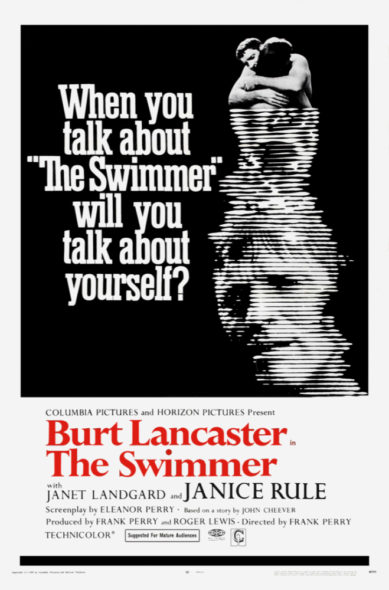

“DEATH OF A SALESMAN in swimming trunks” is how the late Burt Lancaster described his 1968 starring vehicle THE SWIMMER. A better description, I believe, would be “THE TRIAL in swimming trunks,” as the film is authentically Kafka-esque, or perhaps “THE STRANGER in swimming trunks,” as its portrait of alienation is one that remains potent and profound.

“DEATH OF A SALESMAN in swimming trunks” is how the late Burt Lancaster described his 1968 starring vehicle THE SWIMMER. A better description, I believe, would be “THE TRIAL in swimming trunks,” as the film is authentically Kafka-esque, or perhaps “THE STRANGER in swimming trunks,” as its portrait of alienation is one that remains potent and profound.

“DEATH OF A SALESMAN in swimming trunks”

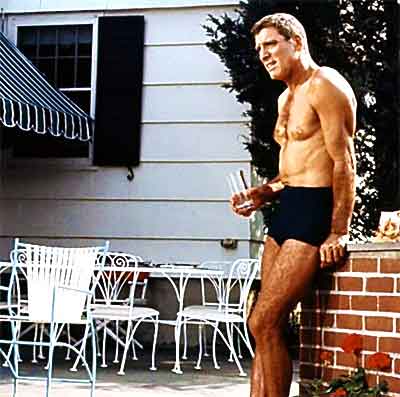

In what might have been intended as a surreal study in self-deception, a satirical critique of late-sixties affluence or an extended daydream, THE SWIMMER begins with the fortyish suburbanite Ned (Lancaster) frolicking in a friend’s backyard swimming pool one languid summer morning. On a whim, Ned decides to “swim home” by taking a dip in all the neighborhood pools. He views himself as an explorer in this strange suburban landscape, and indeed he is, although his journey up the “Lucinda River” turns out to be psychological above all else.

…a surreal study in self-deception, a satirical critique of late-sixties affluence or an extended daydream…

During his swim home he’s subjected to all sorts of humiliations at the hands of various friends and ex-lovers, who all seem to know more about Ned’s situation than he does. Among the revelations they offer are the fact that his wife Lucinda, who Ned makes sure to talk up to anyone who will (or won’t) listen, has left him, and his children, who supposedly “worship” him, are miscreants who think their father is a joke—while he himself is an unemployed alcoholic. As for the “home” he’s heading toward, it’s revealed, in the unforgettable final scene, to not be very homey at all.

The Swimmer Trailer

The production was a troubled one (more on that in a bit), and the finished product contains more than a few flaws, but on balance THE SWIMMER is a stunner. Its portrayal of East Coast affluence (the film was shot on location in Westport, Connecticut) is as suffocating and oppressive as the prisons of PAPILLON and MIDNIGHT EXPRESS, a perfect place to completely lose one’s bearings in the way Ned does—and a terrible one to stage a spiritual rebirth of the type he attempts. Lancaster’s muscular yet brooding physique fits the role perfectly, as his every gesture seems tampered with none-too-hidden despair, and the supporting cast, which includes a debuting Joan Rivers in a cameo, offers a colorful assortment of waspy assholes.

It’s a measure of THE SWIMMER’s brilliance that its narrative structure was able to accommodate such a disparate 25-years-after-the-fact variation, and that it remains such a vital film even though over half a century has passed since its completion.

The film’s basis was a New Yorker short story by John Cheever (1912-1982), the so-called “Chekhov of the suburbs.” A shrink once described Cheever as “a neurotic man, narcissistic, egocentric, friendless (and) deeply involved in (his) own defensive illusions,” which perfectly sums up Ned—or “Neddie,” as he’s identified in the story. The New Yorker’s editors were bewildered by that story, and stuck it at the end of the July 18 issue, but it went on to become one of Cheever’s most famous works. That’s evident in the fact that it was adapted for film, courtesy of mega-producer Sam Spiegel (who ultimately removed his name from the credits), Burt Lancaster and the husband-wife team of Frank and Eleanor Perry, with the former directing and the latter scripting.

The Perrys had made their mark back in 1962, with DAVID AND LISA. A staunchly independent production that went on to enjoy enormous critical and popular success, and nabbed Oscar nominations for both Frank and Eleanor, DAVID AND LISA can be viewed as the BLOOD SIMPLE or SEX, LIES AND VIDEOTAPE of its day. The couple’s 1963 follow-up LADYBUG LADYBUG was considerably less successful (although it’s arguably held up much better), resulting in three years of unemployment for Frank (with Eleanor doing slightly better).

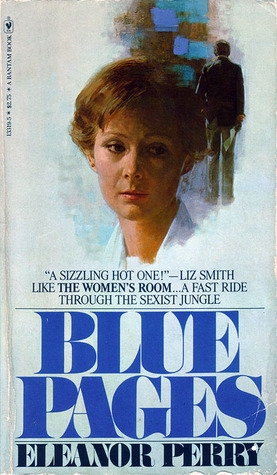

All this is recorded in Eleanor Perry’s 1979 novel BLUE PAGES. Fiction it may be, but like Peter Viertel’s WHITE HUNTER, BLACK HEART, Carol Speed’s INSIDE BLACK HOLLYWOOD and Charles Bukowski’s HOLLYWOOD, the events it relates are staunchly fact-based. Told in mordant prose that foreshadows more notorious Hollywood bitch-fests like YOU’LL NEVER EAT LUNCH IN THIS TOWN AGAIN, BLUE PAGES’ main subject is the shattered marriage between “Vincent Wade” and his wife “Lucia.” That Lucia/Eleanor never quite got over the split is made evident throughout the novel, which is focused primarily on Vincent/Frank, who’s made out to be mean, selfish, insecure, sexist and, most prominently, overweight (lots of wordage is devoted to his flabby physique), although the author doesn’t go too easy on his better half, a woman who apparently “couldn’t admit, even to herself, that she’d been dreaming the wrong dream.”

All this is recorded in Eleanor Perry’s 1979 novel BLUE PAGES. Fiction it may be, but like Peter Viertel’s WHITE HUNTER, BLACK HEART, Carol Speed’s INSIDE BLACK HOLLYWOOD and Charles Bukowski’s HOLLYWOOD, the events it relates are staunchly fact-based. Told in mordant prose that foreshadows more notorious Hollywood bitch-fests like YOU’LL NEVER EAT LUNCH IN THIS TOWN AGAIN, BLUE PAGES’ main subject is the shattered marriage between “Vincent Wade” and his wife “Lucia.” That Lucia/Eleanor never quite got over the split is made evident throughout the novel, which is focused primarily on Vincent/Frank, who’s made out to be mean, selfish, insecure, sexist and, most prominently, overweight (lots of wordage is devoted to his flabby physique), although the author doesn’t go too easy on his better half, a woman who apparently “couldn’t admit, even to herself, that she’d been dreaming the wrong dream.”

Also discussed is the making of THE SWIMMER, or “The Nearest Exit,” with producer “Omar Lederman” seducing the couple into allowing him to oversee the production. In a series of skirmishes whose truthfulness was largely confirmed by the 2014 documentary THE STORY OF THE SWIMMER (found on the Grindhouse Releasing SWIMMER Blu-ray), Lederman/Spiegel attempts to get Lucia/Eleanor to make the script more commercial, with added sex and a happy ending. She resists, only to run into more trouble in the form of movie star “John Matheson” (Lancaster), who initially seems “low-keyed, gracious and crazy about the project,” but doesn’t get along with his director (the abovementioned Joan Rivers cameo, for instance, reportedly took nine days to shoot due to the fact that director and star couldn’t agree on how to depict it).

The Story of the Swimmer (Documentary)

Eventually Lederman/Spiegel flexed his muscles, ordering a crucial scene to be reshot with a different actress (as he found the first one “Ugly! I despise ugly women!”), and replaced Vincent/Frank with “Ellis Taylor” (Sidney Pollack), which explains the discordant nature of the finished film. Lacking is the slickness that marks out most of Frank Perry’s (and Sidney Pollack’s) other films, with much mismatched footage and some questionable artistic choices–such as a slow motion run through a field, an example of the obnoxious pastoral montages so popular in sixties cinema (an element bequeathed, most likely, by the fact that the film was lensed in 1966 but not released until two years later). The film overall still works, but it might have interesting to see what Frank Perry had come up with were he allowed to finish THE SWIMMER on his own terms. As it happened, Columbia pulled the plug before the shoot was complete, forcing Lancaster to fund the final day of filming himself.

Eventually Lederman/Spiegel flexed his muscles, ordering a crucial scene to be reshot with a different actress (as he found the first one “Ugly! I despise ugly women!”), and replaced Vincent/Frank with “Ellis Taylor” (Sidney Pollack), which explains the discordant nature of the finished film. Lacking is the slickness that marks out most of Frank Perry’s (and Sidney Pollack’s) other films, with much mismatched footage and some questionable artistic choices–such as a slow motion run through a field, an example of the obnoxious pastoral montages so popular in sixties cinema (an element bequeathed, most likely, by the fact that the film was lensed in 1966 but not released until two years later). The film overall still works, but it might have interesting to see what Frank Perry had come up with were he allowed to finish THE SWIMMER on his own terms. As it happened, Columbia pulled the plug before the shoot was complete, forcing Lancaster to fund the final day of filming himself.

Eleanor Perry’s other major SWIMMER-related literary effort was the film’s 1967 novelization. That book is actually a transcription of the screenplay, and a none-too-disguised one, retaining the present-tense description and character name-designated dialogue. This means the book doesn’t satisfy as a novel, but it does show how strong the script was, expanding and even, in some respects, improving upon the Cheever text.

Cheever’s narrative was reordered considerably by Eleanor Perry (such as a public swimming pool encounter that occurred near the beginning of the story serving as the climax of the screenplay), but in a manner that stays true to the story. Ditto a Perry-invented portion in which Ned and a young boy air swim through a drained pool, after which Ned, upon walking away, becomes terrified when he hears the boy jumping on the diving board, fearing he may be trying to jump into the waterless pool—thus proving that Ned is not quite as delusional as he comes off.

Cheever’s narrative was reordered considerably by Eleanor Perry (such as a public swimming pool encounter that occurred near the beginning of the story serving as the climax of the screenplay), but in a manner that stays true to the story. Ditto a Perry-invented portion in which Ned and a young boy air swim through a drained pool, after which Ned, upon walking away, becomes terrified when he hears the boy jumping on the diving board, fearing he may be trying to jump into the waterless pool—thus proving that Ned is not quite as delusional as he comes off.

Later film projects made by the Perrys include the dark coming-of-age drama LAST SUMMER (1969) and a trio of Truman Capote adapted made-for-TV films that were combined to form TRILOGY (1969). Finally there was DIARY OF A MAD HOUSEWIFE (1970), which in a definite case of life imitating art was about the breakup of a marriage (and whose making gets fictionalized in BLUE PAGES).

From there Frank Perry went his own way, directing the non-Eleanor scripted films DOC (1971), PLAY IT AS IT LAYS (1972), MAN ON A SWING (1974) and RANCHO DELUXE (1975)—all box office flops—before bottoming out entirely with the eighties camp classics MOMMIE DEAREST (1981) and MONSIGNOR (1982). Thankfully his final film ON THE BRIDGE, an intimate and absorbing 1994 documentary about his own battle with prostate cancer (which would do him in the following year), emerged as one of his better films, and made for a fitting send-off.

Eleanor Perry wasn’t quite as fortunate. Her only notable post-1970 credits were as co-scripter of the Rene Clement kidnapping thriller THE DEADLY TRAP (1971) and screenwriter of the Burt Reynolds vehicle THE MAN WHO LOVED CAT DANCING (1973)—or, as it’s identified in BLUE PAGES, “THE LADY AND THE ROBBER.” She died in 1981.

Eleanor Perry wasn’t quite as fortunate. Her only notable post-1970 credits were as co-scripter of the Rene Clement kidnapping thriller THE DEADLY TRAP (1971) and screenwriter of the Burt Reynolds vehicle THE MAN WHO LOVED CAT DANCING (1973)—or, as it’s identified in BLUE PAGES, “THE LADY AND THE ROBBER.” She died in 1981.

Burt Lancaster, who was known to alternately dismiss THE SWIMMER as “a disaster” and proclaim it the best film of his career, went on to appear in several more eccentric film projects, including CASTLE KEEP (1969), CONVERSATION PIECE (1974), BUFFALO BILL AND THE INDIANS (1976) and CONTROL (1987), before passing on in 1994. As for Sam Spiegel, he only turned out three more films (none of them very successful) prior to his 1985 demise.

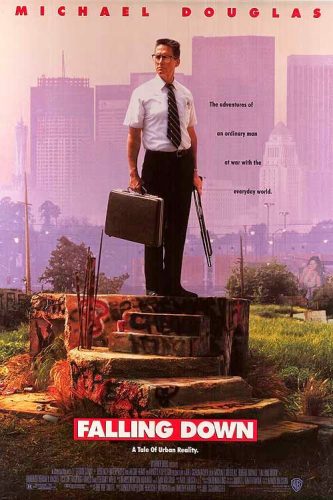

THE SWIMMER itself didn’t fare too well commercially, and quickly disappeared from view. Yet it never entirely vanished from the public consciousness, having been singled out in many an op-ed piece as an example of Hollywood wrong-think (when it was actually a rare instance of Tinseltown attempting to create something unique and interesting). It was also given an uncredited remake in 1993, in the form of Joel Schumacher’s FALLING DOWN.

The connection between the two films may seem difficult to discern, but it exists. FALLING DOWN’s Michael Douglas essayed protagonist, a businessman identified as “D-Fens,” finds himself stuck in traffic in downtown LA one morning, and abruptly decides to abandon his car and walk back to his Venice Beach home. The only thing is that, as with Ned Merrill, that “home” no longer exists, with D-Fens’ wife having left him and the job he was supposedly heading toward no longer existing.

The connection between the two films may seem difficult to discern, but it exists. FALLING DOWN’s Michael Douglas essayed protagonist, a businessman identified as “D-Fens,” finds himself stuck in traffic in downtown LA one morning, and abruptly decides to abandon his car and walk back to his Venice Beach home. The only thing is that, as with Ned Merrill, that “home” no longer exists, with D-Fens’ wife having left him and the job he was supposedly heading toward no longer existing.

Falling Down Trailer

Thus D-Fens embarks on a highly picaresque odyssey through LA at the time of the 1992 riots (which occurred while the film was being shot). The addition of Robert Duvall as a pesky detective was a mistake, but Schumacher succeeds in adroitly turning Frank and Eleanor Perry’s withering critique of sixties suburban ennui into an even more savage lament for the decline of America’s middle class that occurred in the nineties. It’s a measure of THE SWIMMER’s brilliance that its narrative structure was able to accommodate such a disparate 25-years-after-the-fact variation, and that it remains such a vital film even though over half a century has passed since its completion.