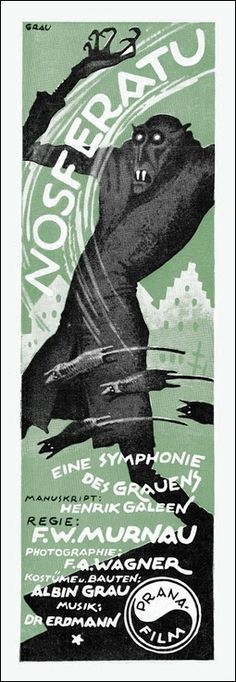

March, 2022 marked a most auspicious anniversary: the centennial of NOSFERATU, EINE SYMPHONIE DES GRAUENS. The first and only film made by Germany’s Prana-Film, NOSFERATU was an unabashed plagiarization of Bram Stoker’s DRACULA, with screenwriter Henrik Galeen following the novel’s narrative quite closely, albeit with the character names altered. Those name changes started with the title character becoming Count Orlock (or, as his moniker is rendered in many English language prints, Nosferatu), essayed by Max Schreck (1879–1936).

NOSFERATU (1922) Director Murnau

All this is rendered palatable due to the artistry of NOSFERATU’S director, the incomparable Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau (1888-1931). A protégé of the legendary theater director Max Reinhardt, Murnau had directed several films prior to NOSFERATU (including 1919’s SATANAS and the 1920 DR. JECKYLL AND MR. HYDE knock-off THE HEAD OF JANUS/DER JANUSKOPF), most of which are now lost.

NOSFERATU, Murnau’s first great success, was designed by producer/artist/occultist Albin Grau (1884–1971). Grau was instrumental in setting up the film, and the short-lived Prana, as an expression of his occult beliefs—beliefs allegedly shared by Murnau. A wealth of occult symbols were worked into NOSFERATU, which gives voice to Grau’s claim that “In cinema shadow is more important than light. Cinema is the language of shadows. Through shadow, the hidden and dark forces become visible.”

Filming, which took place in in Slovokia and Germany, was accomplished on a painfully low budget. That’s evident in the paucity of locations, most of which tended to be crowded together (see the 2007 documentary THE LANGUAGE OF SHADOWS, which provides a careful recounting of NOSFERATU’S filming locations), and also the fact that so much of this “Symphony of Moonlight and Nightmares” was filmed in broad daylight, a fact made all-too-overt in the many prints in circulation that don’t contain the color tinting utilized by Murnau.

No, time hasn’t been entirely kind to it, but I feel NOSFERATU is a more enduring film than DRACULA (1931), an authorized but far less audacious adaptation of Stoker’s novel. NOSFERATU is noteworthy, first and foremost, for taking vampirism from the stately Victorian settings of Stoker’s novel to a more squalid and uneasy realm. That’s evident in the still-effective sight of the bald Orlock, who sports two formidable fangs jutting from the center of his mouth and exists, essentially, as a two-legged rat with a queasy sexual undertow (“everything about him,” according to one description, “is pointy”)

Other unique elements include the transposition of the action to the Biedermeier epoch of the 1800s, with much of Murnau’s imagery recreated from paintings of the period by Caspar David Friedrich, Moritz von Schwind and George Freidrich Kirsting. The addition of bubonic plague, spread by rats that accompany Orlock on his sea voyage from Transylvania to Germany, was another novel element (and quite timely in 1922, seeing as how the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918 was still fresh in the collective psyche). The film also contains what is said to be the cinema’s first-ever depiction of a vampire being vanquished by sunlight.

In accessing NOSFERATU we’ll also have to take into account the German Expressionist film boom of the late 1910s and 20s. Expressionist cinema, which in keeping with movement’s overall aims sought to visualize interior states through distorted and unreal imagery, includes THE GOLEM/DER GOLEM, GENUINE, WAXWORKS/DAS WACHSFIGURENKABINETT, and, of course, THE CABINET OF DR. CALIGARI/DAS CABINET DES DR. CALIGARI, which single-handedly defined the Expressionist movement (and, some have claimed, the entirety of German cinema). That film’s blatantly artificial painted backdrops are belied by NOSFERATU’s practical settings, which are if not a problem than at least a drawback, as one senses throughout that Murnau would have preferred to work with the more pliable stage-bound scenery that graced CALIGARI.

NOSFERATU’s Expressionist bonafides are, however, evident in the geometric shadows, evocatively framed scenery (note the church that in one crucial scene all-crowds out a coffin-carrying Orlock) and impossible-to-forget images of a procession of coffins, an empty ship floating toward a docking port and Nosferatu’s clawed shadow reaching for a doorknob (never mind that vampires aren’t supposed to cast shadows). Such a concentration on visual design, alas, has its drawbacks; a 1928 critic complained, persuasively, that the proceedings were “nearer to a photo album than a film,” with characters, including the Jonathan Harker inspired Hutter (Gustav von Wangenheim) and the Van Helsing inspired Knox (Alexander Granach), that tend to fade into the background.

Any discussion of NOSFERATU must take into account the legal crusade brought against the film by Bram Stoker’s widow Florence. Her onslaught was financially motivated in its early stages, but after three years of fruitless legal maneuvering Stoker changed her tactics, advocating for the film’s complete obliteration. In this gambit she was successful, with a German court issuing a 1925 order that all existing prints of NOSFERATU be destroyed. Thankfully some copies survived the purge, although it took until 2006 for an authoritative restoration, with the original color tinting, orchestral score and 94 minute runtime, to surface.

See also: NOSFERATU THE VAMPYRE | HOLLYWOOD GOTHIC: THE TANGLED WEB OF DRACULA FROM NOVEL TO STAGE TO SCREEN | DRACULA BY BRAM STOKER (Book) | KEN RUSSELL’S DRACULA (Screenplay)

Critical reception during the film’s American theatrical run (before it was cut short by Florence Stoker) was generally on the negative side. It seems 1920s viewers had trouble reconciling NOSFERATU’S unremitting concentration on D-words (death, disease, decay, etc.) with its poetic veneer (to parrot a claim made about Paul Schrader’s CAT PEOPLE, it was “too bloody for the art crowd and too arty for the blood crowd”), although I’d argue it’s that very dichotomy that provides the film’s major 100-years-after-the-fact point of interest.

NOSFERATU has, mixed reception or not, proven quite influential. The 1931 DRACULA (which Murnau, who was killed in a March ‘31 automobile accident, didn’t live to see) bears its unmistakable influence, as does Tobe Hooper’s SALEM’S LOT (1979), whose head vampire Kurt Barlow (Reggie Nalder) was deliberately patterned after Max Schreck in Murnau’s film. Then there was the 1979 remake by Werner Herzog.

A German-French co-production distributed in the US by 20th Century Fox, Herzog’s NOSFERATU THE VAMPYRE took the original film’s corrosive vision even further, creating a lyrical ode to death and madness. Author David J. Skal, in his acclaimed DRACULA study HOLLYWOOD GOTHIC, dismisses Herzog’s NOSFERATU as “wrong-headed and rather pretentious,” and American audiences, who in a test screening so detested the film they allegedly provided their own category—“the Pits”—on the evaluation cards, evidently agreed.

Herzog’s aims weren’t too dissimilar to those of Gus Van Sant in his 1998 remake of PSYCHO, which is to say that he sought to create a near shot-by-shot replication of the older film, lensed in many of the same locations. Herzog, however, succeeded in adding a great deal of his own by removing all the conventionally “scary” bits and slowing the pace down considerably. What remains is an unforgettable succession of images detailing a descent into a new (and, as implied by the FEARLESS VAMPIRE KILLERS inspired ending, possibly better) undead world.

Klaus Kinski, Herzog’s favored co-star, is simply magnificent as Dracula (the name having been changed back to Stoker’s original conception), a tormented being who feels at peace only when drinking somebody’s blood—and so is far removed from the soulless creature incarnated by Max Schreck. Other striking performances are delivered by the late artist/writer Roland Topor as Renfield (a name likewise changed back from Murnau’s film, where the character was known as Knock), Bruno Ganz as Jonathan Harker and Isabelle Adjani as Lucy Harker.

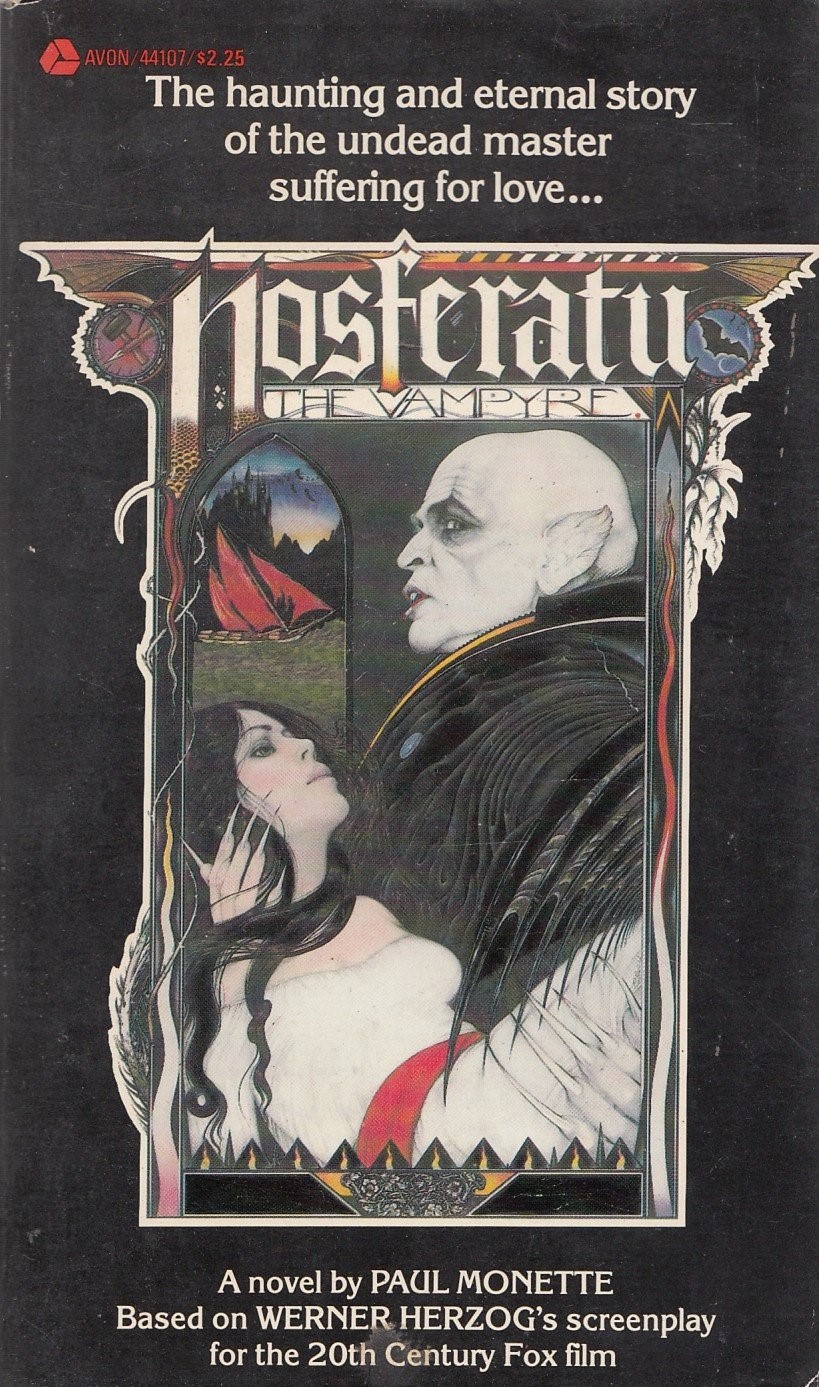

While on the subject of Herzog’s NOSFERATU, the late Paul Monette’s novelization of the film is of definite worth, a deeply felt, sensuous reverie that nearly works as a standalone novel. Not quite, though: it’s clunky, as most movie novelizations tend to be, grouped into lengthy paragraphs that tend to repel, rather than compel, attention. Monette was given a writing time-frame that was by his own admission “insane,” and so clearly missed out on a lot of much-needed revision time.

Still, what Monette achieved with this slender book is impressive. Herzog’s film was, despite its visual brilliance, a rather thin one, in keeping with its source material. Monette filled in the back stories Herzog and Murnau left out, and bulked up the characterizations in the process, with a uniquely provocative, hallucinatory touch that puts the book over the top.

NOSFERATU A VENEZIA/VAMPIRE IN VENICE is an ersatz sequel to Herzog’s film that premiered in 1988. The credited writer-director was the film’s producer Augusto Caminito, who took over directing duties after firing three previous helmers. It’s set, as the title portends, in Venice, where a slumming Christopher Plummer, playing a fearless vampire hunter, is looking to do battle with the feared Nosferatu. Klaus Kinski reprises the role (at a point in his career when his behavior had become unbearable—by ’88 even Herzog had stopped working with him), albeit with a full head of hair (Kinski having refused to shave his head for the role) and a penchant for pushing people out the window of an upper floor of a Venetian flat, to get impaled on the spiked fence below. Precisely what the film, with its distracting techno-score and thoroughly dull, unimaginative narrative, has to do with Herzog (much less Murnau) is anyone’s guess.

VAMPIRE IN VENICE (Trailer)

In 1991 there appeared a two issue NOSFERATU comic adaptation. In this ambitious saga Rafael Nieves and Ken Holewczynski replaced F.W. Murnau’s Expressionist visuals with black and white imagery rendered, more often than not, as oft-indistinct lines and shapes amidst a sea of darkness. The figure of Orlock/Nosferatu is at least faithfully replicated by Nieves and Holewczynski, who borrow Bram Stoker’s conceit of relating the story through a supporting character’s journal entries (something that wasn’t part of the Murnau and Herzog films, nor the Monette novel). They also jimmy with the chronology somewhat, but otherwise the comic follows the film nearly verbatim.

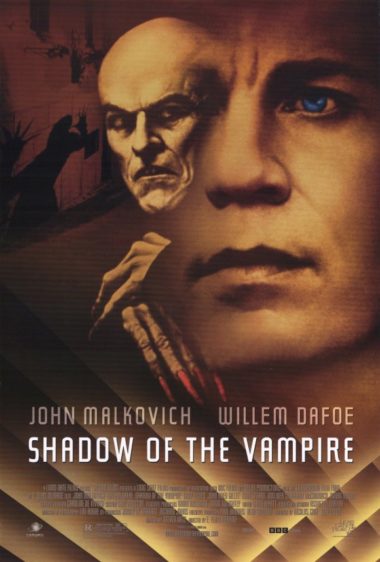

Finally we have SHADOW OF THE VAMPIRE (2000), which alleged to document the making of F.W. Murnau’s classic. John Malkovich plays Murnau and an over-the-top Willem Dafoe essays Max Schreck (a role that was, believe it or not, Oscar nominated). The film’s conceit is that Schreck was in fact a real vampire looking to feast upon Murnau’s crew, thus allowing the filmmakers to make a number of sophomoric points about illusion vs. reality, the psychic tyranny of the artistic impulse and so forth.

SHADOW OF THE VAMPIRE (Trailer)

The definitive post-modern take on NOSFERATU was already done in Herzog’s abovementioned 1979 film, of which the silly and pretentious (but impressively visualized) SHADOW OF THE VAMPIRE is but a pale shadow. To add insult to injury, its director was E. Elias Merhige, the brains behind 1989’s BEGOTTEN, a film I’d argue was as bold and revolutionary as the original NOSFERATU—a formidable compliment indeed!