No other filmmaker has become as synonymous with Underground Film as the late Kenneth Anger. His early shorts, which include EAUX D’ARTIFICE (1953), INAUGURATION OF THE PLEASURE DOME (1954) and LUCIFER RISING (1972), are among the most widely viewed underground films of all time, with his SCORPIO RISING (1963), being quite possibly the most recognizable, and widely imitated, such film that exists (with its use of montage editing and pop music littered soundtrack having proven extremely influential in the succeeding decades).

The American underground film movement was already up and running by 1947, when Anger made his first “public film,” the enormously controversial FIREWORKS. Maya Deren’s MESHES OF THE AFTERNOON (1943) preceded it, as did Curtis Harrington’s FRAGMENT OF SEEKING (1946), poetic and surreal “trance films” both. Anger provided a similar aesthetic, albeit with a violent, confrontational edge.

In person Anger was known to project, in the words of one unnamed journalist, “a certain power that one finds in both geniuses and madmen,” yet he also fully exhibited his upper class Beverly Hills upbringing. As anyone who’s listened to his DVD audio commentaries will recognize, his soothing and melodic speech pattern made for a jarring contrast to the confrontational persona he liked to project. Further contrast was provided by Anger’s physical appearance, which was always impeccable, confirming the British documentarian Nigel Finch’s claim that “Image is very important to him.”

Anger was also quite open about his homosexuality, although that aspect tends to be overrepresented by commentators. When asked by Finch if the much-remarked-upon homoerotic imagery of FIREWORKS was intended as a “gay statement,” Anger replied “at that time there were very few statements of any kind being made along those lines.”

Anger once claimed “the day that cinema was invented was a black day for mankind.” He viewed films as talismanic objects imbued with demonic “magick” of which he, a devoted follower of Aleister Crowley, eagerly partook: “I consider myself as working Evil in an evil medium.” If a talent for creating hypnotically incantatory imagery with an obsessive edge—bejeweled lighting, hermetic symbolism, unalloyed sadomasochism and fetishistic depictions of the male anatomy being constants—is “Evil” than Anger was indeed “working” that evil to its fullest.

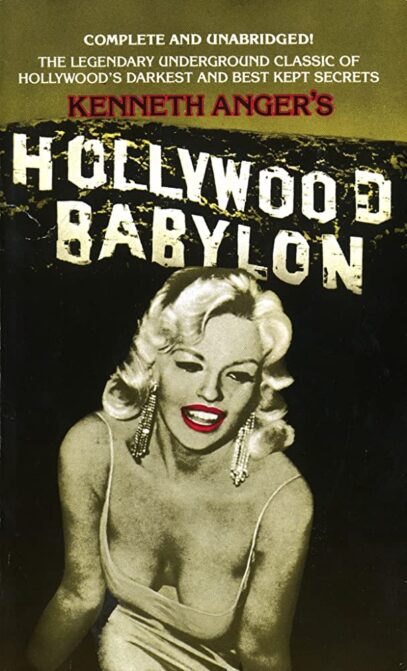

Anger was also responsible for the legendary gossip compendium HOLLYWOOD BABYLON, which despite a troubled publication history (its initial 1965 English language printing was bowdlerized, with the Anger authorized version taking until ‘75 to appear) is one of the Twentieth Century’s key film texts. The book has been widely criticized, yet it spawned a virtual industry, with non-Anger affiliated knock-offs like TV BABYLON and COUNTRY BABYLON proliferating. Those books, alas, completely missed the fascination of HOLLYWOOD BABYLON, in which Anger aired a disdain for the excesses of old Hollywood as well as a healthy reverence for it. “I love Hollywood,” he told Finch, “it had many things wrong with it…and yet many things were right with it.” A HOLLYWOOD BABYLON II appeared in 1984, but Anger admitted it was strictly a cash-grab.

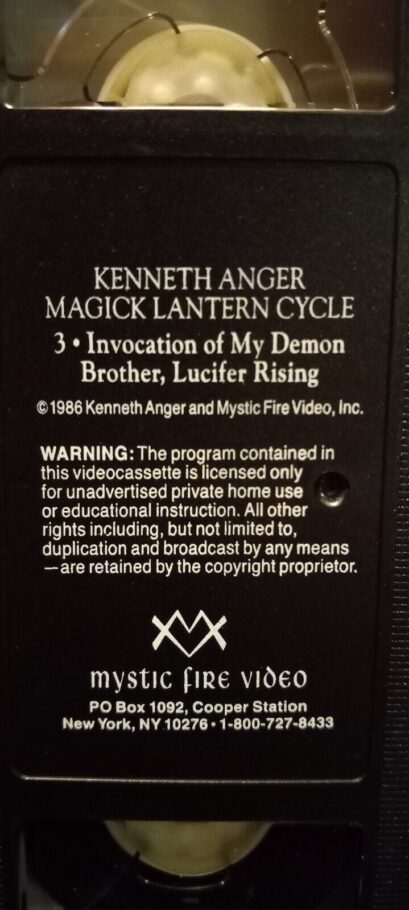

It was of course Anger’s filmmaking endeavors that brought him the most notoriety. MESHES OF THE AFTERNOON and FRAGMENT OF SEEKING largely faded from view after their bravura debuts, while Anger’s early films were in constant circulation through the 1960s and 70s, often in the form of a compilation he called THE MAGICK LANTERN CYCLE. They were also among the first underground films to be commercially released on VHS in the 1980s, courtesy of Mystic Fire Video (although Anger, who liked to periodically rehash his work, wasn’t too happy with those releases).

It was of course Anger’s filmmaking endeavors that brought him the most notoriety. MESHES OF THE AFTERNOON and FRAGMENT OF SEEKING largely faded from view after their bravura debuts, while Anger’s early films were in constant circulation through the 1960s and 70s, often in the form of a compilation he called THE MAGICK LANTERN CYCLE. They were also among the first underground films to be commercially released on VHS in the 1980s, courtesy of Mystic Fire Video (although Anger, who liked to periodically rehash his work, wasn’t too happy with those releases).

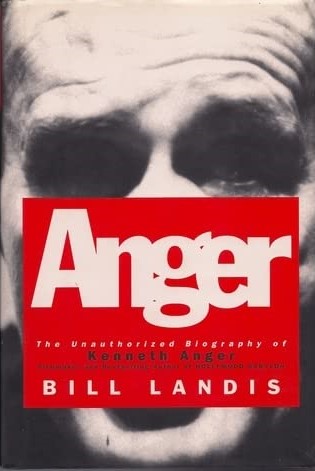

If Bill Landis’ 1996 biography ANGER is to be believed, Anger viewed his short films as stepping stones to bigger and better things. Obsessed with teenagers of the 1960s (as exhibited in his never-completed 1965 short KUSTOM KAR KOMMANDOS), Anger apparently fancied himself a proto-John Hughes, yearning to make “a good teenage film, that would still be for them, and that wouldn’t get the parents upset about their kiddies seeing it.” Needless to say, that film never reached fruition, and neither did a proposed Hollywood biopic about Anger’s lifelong idol Aleister Crowley, or a feature film adaptation of HOLLYWOOD BABYLON.

One major problem facing Anger seems to have been that he did his job a bit too well. The images he created–the firecracker phallus of FIREWORKS, the orgasmic water spouts of EAUX D’ARTIFICE, Anais Nin’s birdcage head ornament in INAUGURATION OF THE PLEASURE DOME, the orange UFO floating over the Luxor Temple in LUCIFER RISING—were so indelible few people in the industry saw any reason to upgrade his means. There was also the sad-but-true fact that, as Landis made clear toward the end of ANGER, “America refuses to support its artists.”

I should add here that Anger really despised ANGER, and claimed to have put a curse on its author (apparently unaware that no curse could compete with Landis’ awesomely self-destructive tendencies). Yet I say ANGER is a superlative work: exhaustively researched and, based on what I’ve gleaned about its subject, fairly accurate. In other words, its portrayal of a gifted but tempestuous filmmaker who alienated nearly everyone he ever met seems pretty spot-on.

Which brings us to another major issue that dogged Kenneth Anger: he lived up to his name all too well. It’s certainly not unusual for film directors to become bitter recluses in their later years, but Anger took that tendency to an extreme.

For evidence see a spectacularly bitchy self-penned biographical sketch in a program for a spring 1966 NYC screening of the MAGICK LANTERN CYCLE. Among its claims: “No filmmaker in our times is misunderstood more than Kenneth Anger,” a man who apparently “wanders over the whole globe and finds only misunderstanding everywhere.”

See also a collection of Xeroxed clippings, apparently put together by Anger himself, entitled KENNETH ANGER’S MAGIC QUEST and bearing a 1989 copyright date (and a publisher identified as “19 Temple USA Publications”). It consists of articles about, and interviews with, Anger (including a newspaper story about the arrest of several motorcycle gangs alongside a handwritten scrawl reading “MY VINDICATION…Life Mimics Magick Movie Art”), which provide a good indication of his mindset.

An interviewer’s question about which contemporary filmmakers Anger respects yields a most succinct answer: “None.” In the same interview his onetime colleague Mick Jagger is dubbed a “fucking bastard,” and another 1960s icon gets an even more dismissive treatment: “I refuse to discuss Andy Warhol under any circumstances.” Anger also claims to have been “ripped off” by Dennis Hopper and Ken Russell, and raped by Mickey Rooney at age six. One of the interviews is prefaced by an admission that “It was not with overwhelming enthusiasm that we decided to print the following interview with Kenneth Anger,” citing “extreme objections by members of the editorial staff” to his “cynicism and misanthropy.”

That misanthropy wasn’t entirely unjustified, given that Anger’s fortunes declined rather precipitously in the eighties and nineties. Stalled projects (including a never-published HOLLYWOOD BABYLON 3) and financial uncertainty were constants, with Anger, according to Landis, gravitating “toward old Hollywood friends who (clung to) their own memories of what Tinsel Town used to be.” Among them was the late Forrest J. Ackerman, in whose memorabilia-filled Hollywood mansion “One would pass the robot from METROPOLIS, the toys from KING KONG, and Anger. Anger sat resolutely as a monk.”

You can be forgiven for have deduced (as I did) in the late nineties that Anger was headed for an end not dissimilar to the gruesome celebrity suicides he detailed in HOLLYWOOD BABYLON. Yet in 1999 Anger returned to filmmaking (after a 23 year absence) with DON’T SMOKE THAT CIGARETTE, a cheeky reedit of a 1980s anti-smoking PSA. An original work it wasn’t, but it did feature a lot of recognizable Anger elements—pop tunes, homoerotic biker imagery, rapid-fire editing—and sparked a new creative thrust.

Anger spent the next decade engaged in creating a new Magick Lantern cycle of short films. Those films, which included THE MAN WE WANT TO HANG (2002), MOUSE HEAVEN (2004), BRUSH OF BAPHOMET (2009) and AIRSHIPS (2013), weren’t exactly Magickal, but it was good to see Anger putting aside his despondency (at least a while) and renewing his creative fire. He may not have approached the excellence of his earlier films, but even a lesser Anger effort is well worth one’s while.