In a 1995 recollection, Kevin Smith, while promoting his no-budget debut feature CLERKS (1994), “sat down with” Martin Scorsese’s then-girlfriend Illeana Douglas. Smith naturally wanted to know if the great man had seen CLERKS—he had—and how he responded. Douglas claimed her BF liked the film but had a negative reaction to its final moments, in which Spike Lee, Jim Jarmusch, Richard Linklater and Hal Hartley were credited with “leading the way” for independent filmmakers. “Oh,” Scorsese is said to have responded, “they led the way.”

Scorsese was right to be upset. There existed many independent movie way-leaders before those four names mentioned by Smith, including Scorsese himself, John Sayles, Melvin Van Peebles, John Cassavettes and John Carpenter—yes, the so-called “Horror Master” John Carpenter, a filmmaker whose influence on American cinema (not just American horror cinema) has been vastly underrated.

The aesthetic qualities of Carpenter’s films are certainly worth enumerating. My primary interest here, however, is in how those films and their maker transformed Hollywood (and not always for the better).

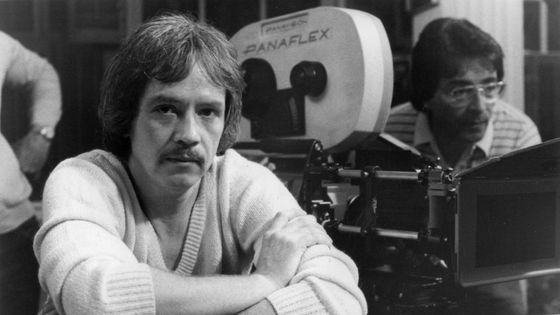

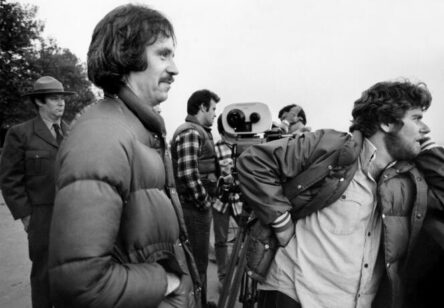

The Kentucky born John Carpenter got his start, as did quite a few other prominent Hollywood figures, in the 1970s. Back then there existed many influential moviemaking cliques, led by charismatic figures like Francis Ford Coppola (who counted George Lucas, John Milius and Philip Kaufman among his acolytes) and Martin Scorsese (whose crew included Thelma Schoonmaker and Harvey Keitel).

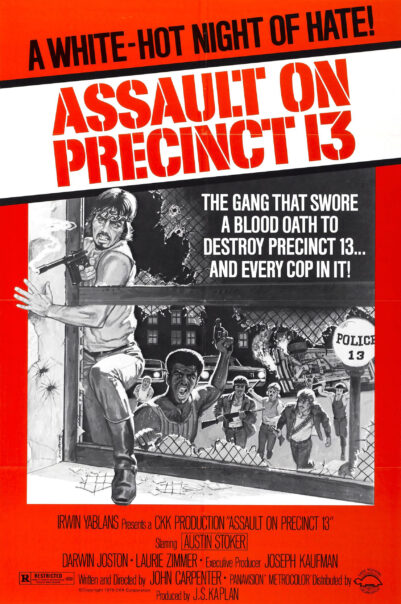

Carpenter had his own clique, which included the late Debra Hill (1950-2005), an assistant editor on ASSAULT ON PRECINCT 13 (1976) who was elevated to producer and co-writer of HALLOWEEN (1978), and went on to become an important Hollywood player. Other Carpenter alumni include Nick Castle, a film school chum who played Michael Myers in HALLOWEEN and co-scripted ESCAPE FROM NEW YORK (1981), and became a respected director with credits that include THE LAST STARFIGHTER (1984) and DENNIS THE MENACE (1993), and Tommy Lee Wallace, a Carpenter friend from childhood onward who got his start working on his pal’s films and is now a prolific director of episodic television, and HALLOWEEN III: SEASON OF THE WITCH (1982).

This brings up another Carpenter attribute: the ability to recognize and nurture talent. Wallace, in his book HALLOWEEN 3—-“WHERE THE HELL IS MICHAEL MYERS?”, has admitted that in directing HALLOWEEN III he chose to bring along much of Carpenter’s “family,” but not Randy Moore and Craig Stearns. Together with Wallace, Moore and Stearns formed the Art Department on Carpenter’s early films, yet for his feature directorial debut Wallace passed them over in favor of the more seasoned Peter Jamison. “Should I have applied John’s technique, and given them the chance to step up?” Wallace wrote, admitting “In the end I didn’t and, with all due respect to Peter Jamison, it still bothers me that I didn’t.”

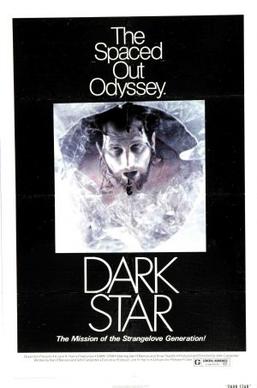

It all began with DARK STAR (1974), a USC student film made by Carpenter and the late Dan O’Bannon (1946-2009), a pair described by Wallace as “two madmen lingering on a campus they’d almost outgrown, making their unusual, and unusually funny, little movie.” The no-budget ingenuity for which Carpenter would become known was very much in evidence in DARK STAR, which attempted a satiric 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY (1968) scaled space epic, and very nearly succeeded. The Carpenter-O’Bannon relationship didn’t succeed, alas, with the two having a falling-out that wasn’t mended until shortly before the latter’s demise.

DARL STAR (Clip)

That Carpenter wasn’t satisfied with the reception of DARK STAR—which was padded to feature length and theatrically released by schlockmeister Jack H. Harris—is indicated by his after-the-fact remarks about it: “I was expecting that the audience would appreciate the struggles I went through to get DARK STAR made. But they don’t care about that. What they just care about is what the finished product is…I had expectations of something else, but it toughened me up for the business.” Unlike so many of his contemporaries (such as George Lucas, who in the early 1970s had great disdain for commercial cinema), Carpenter had no interest in making art films, wanting to play with the big (budget) boys.

Carpenter’s second feature ASSAULT ON PRECINCT 13 was a breakout hit that garnered high praise from Stanley Kubrick (who cast one of its stars, the late Tony Burton, in THE SHINING). A transposition of RIO BRAVO (1959) to inner city Los Angeles, the film’s “Scotch tape and chewing gum” resources weren’t much greater than those of DARK STAR, but on ASSAULT Carpenter introduced a new innovation: the use of expensive Panavision equipment, resulting in Hollywood-worthy widescreen images. This placed Carpenter ahead of his low budget peers, and allowed for something DARK STAR hadn’t achieved: a chance to take on Hollywood directly.

ASSAULT ON PRECINCT 13 (Trailer)

That chance was seized upon most lucratively by HALLOWEEN, which for many years held the title of Most Successful Independent Film of All Time. Even today it has a slickness and grandeur that set it apart, revealing an ability to stretch a (very) low budget that enters genius category.

Another influential (though far from genius) aspect of HALLOWEEN was that it sparked the epidemic of “sequelitis” that permanently felled Hollywood. HALLOWEEN II (1981) was by no means the first major movie sequel, but it was (if Wallace is to be believed) the film that made sequels a viable financial proposition, starting a neverending race to the bottom.

It was inevitable that, following THE FOG (1980) and ESCAPE FROM NEW YORK—which counted among its crew a young James Cameron, Carpenter’s more intense Canadian counterpart—Carpenter would be snatched up by Hollywood. His big studio offerings THE THING (1982), CHRISTINE (1983), STARMAN (1984) and BIG TROUBLE IN LITTLE CHINA (1986) weren’t too successful, and returned him to the low budget sphere. Occasional Hollywood sojourns, such as MEMOIRS OF AN INVISIBLE MAN (1992) and ESCAPE FROM L.A. (1996), followed, but for the most part Carpenter, who stated that the film business was “going in a different direction and I didn’t want to go there,” continued making movies in the arena where many would argue he belonged.

Fast forward to the present: Carpenter hasn’t directed a movie in over a decade, which makes sense, as the type of off-Hollywood success he enjoyed back in the day is no longer possible in today’s increasingly corporatized moviescape. There’s also the fact that his final films, which included GHOSTS OF MARS (2001) and THE WARD (2010), lacked the innovative charge of his earlier efforts. “An analog man in a digital world” is how critic Kent Jones dubbed Carpenter, while Scorsese summed up his work this way: “His pictures always have a handmade quality—every cut, every move, every choice of framing and camera movement, not to mention every note of music (he composes his own scores) feels like it has been composed or placed by the filmmaker himself.”

“Handmade” filmmaking isn’t cool anymore, although Carpenter’s brand of overtly commercial, genre-friendly filmmaking was never too highly respected (among critics, at least). Which brings up another Carpenter attribute: the fact that his films tend to date extremely well, with most of them now viewed as classics, and in some cases (THE THING and 1988’s THEY LIVE in particular) masterpieces. I say the reputation of the man himself needs to follow suit, as it’s past time for this “fine American director” (Scorsese’s words again) to take his rightful place as a true American master.