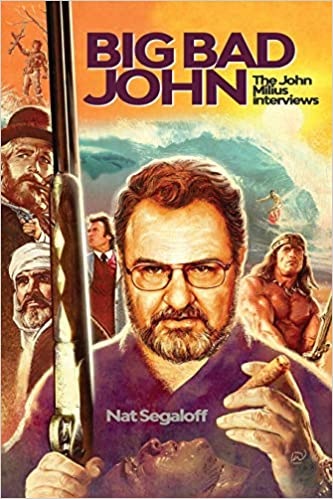

By NAT SEGALOFF (Bear Manor Media; 2021)

By NAT SEGALOFF (Bear Manor Media; 2021)

A book of interviews, conducted by extreme personality enthusiast Nat Segaloff, with the famous screenwriter/director John Milius. Truthfully I’ve always found Milius to be something of a blowhard, a California bred Jewish intellectual who feels the need to maintain, and constantly remind us of, a hyper-macho orientation. You can be sure that in any interview Milius gives he’ll make numerous references to his gun collection and love of all things military (even though he never served), and that’s certainly the case here, in a book whose author admits of his subject that “Although he privately chafes at his public image as a gun-toting, liberal-baiting provocateur, he allows himself to be painted as such, at times even holding the brush.”

Yet for all that I find the man enormously entertaining. Milius’ views, however exaggerated they may be, are always provocative and, given the stultifying homogeneity of most Hollywoodians, refreshingly nonconformist. As he proclaims here, “A lot of the principles by which I live were dead before I was born.” He’s also a writer whose talent is undeniable (a screenwriting instructor I once had warned against including excessive description in one’s script “unless you’re John Milius”) and whose storytelling skills are fully evident in his speech.

“A lot of the principles by which I live were dead before I was born.”

Covered in these interviews are Milius’ privileged upbringing in Malibu, CA (a far cry from the backgrounds of the outlaws, mountain men, soldiers and barbarians that populate his screenplays), during which he cultivated a lifelong love of surfing. He also speaks about attending film school in the late 1960s with a peer group that included Francis Francis Ford Coppola, Steven Spielberg and George Lucas. Milius was unique among that crowd in his right-of-center political leanings, and also the cultivation of a persona that has continually fascinated the media (with Milius inspired characters cropping up in films like AMERICAN GRAFFITI and THE BIG LEBOWSKI).

Milius’ “culturally incorrect” stance may be interesting and even salutary, but it got him into trouble commercially. His celebrated scripts for THE LIFE AND TIMES OF JUDGE ROY BEAN, JEREMIAH JOHNSON and APOCALYPSE NOW were all heavily retooled for their screen incarnations, and his autobiographical surfing epic BIG WEDNESDAY, which felt out of step with late 1970s values, was a notorious flop from which Milius’ career never fully recovered.

His subsequent directorial assignments, such as CONAN THE BARBARIAN, RED DAWN and THE FLIGHT OF THE INTRUDER, have been few and far between, and pulled off with increasingly limited means (or as he puts it, “I have fought all my battles as a guerilla fighter—at night, with no or little ammunition, weapons that were stolen, and usually having to fall back after fighting against superior forces”), with his major source of income coming from uncredited rewrites on movies like DIRTY HARRY, JAWS, LONE WOLF McQUADE and THE HUNT FOR RED OCTOBER.

An afterword informs us that in the years since these interviews were conducted (the last was in 2001) Milius’ fortunes declined precipitously. His already-tenuous film career bottomed out entirely when it was discovered that his assets were being embezzled by an accountant. Even worse, in July of 2010 Milius suffered a debilitating stroke that, tragically for such a skilled raconteur, left him without the ability to speak. Quoted here is Steven Spielberg, who called the stroke “the worst thing that’s ever happened to any of my friends.”

Quoted here is Steven Spielberg, who called the stroke “the worst thing that’s ever happened to any of my friends.”

The book concludes on an unsettled note, with Milius, ensconced in his Brentwood, CA residence, still in recovery. It’s doubtful he’ll be making any more films, and he certainly won’t be giving too many more interviews. It’s a good thing, then, that BIG BAD JOHN exists.