Japanese Cyberpunk: for those familiar with the early-to-mid-nineties films of Shinya Tsukamoto and Shozin Fukui, those two words have a very particular connotation, promising an unflinching exploration of the darkest extremes of technology and madness.

Cyberpunk is a real-life term, certainly, but also a popular science fiction subgenre. William Gibson’s 1983 novel NEUROMANCER marked the official inception of cyberpunk, which continued through the eighties and nineties with Gibson-esque novels like Bruce Sterling’s SCHISMATRIX and Neil Stephenson’s SNOW CRASH, and films like JOHNNY MNEMONIC and THE MATRIX. All were characterized by a hip, street-smart sensibility, gritty futuristic locales and a vivid aura of high-tech romanticism.

For the Japanese, however, cyberpunk appears to mean something else entirely. I’m thinking here of several different but interrelated films by Tsukamoto, Fukui and others, all hailing from the Japanese underground and all sharing a set of distinctly cyberistic themes.

What distinguishes these films is their overpowering concentration on aberrance and grotesquerie within sci fi frameworks. Rather than the romantic techno-vistas of NEUROMANCER, Tsukamoto and co. appear to have taken their inspiration from the outrageous punk-fuelled cinema of Sogo Ishii (BURST CITY, CRAZY FAMILY) and the darkest elements of ERASERHEAD, VIDEODROME and THE TERMINATOR.

Shinya Tsukamoto’s TETSUO: THE IRON MAN kicked off the J-cyber genre in 1990. It was Tsukamoto’s debut and remains his most resonant creation, a whacked-out black and white cyber nightmare accomplished with feverish imagination and a kinetic intensity that has yet to be surpassed. It was made for peanuts, but Tsukamoto threw every conceivable low-rent special effect into the mix regardless of whether his paltry budget could support it or not.

Shinya Tsukamoto’s TETSUO: THE IRON MAN kicked off the J-cyber genre in 1990. It was Tsukamoto’s debut and remains his most resonant creation, a whacked-out black and white cyber nightmare accomplished with feverish imagination and a kinetic intensity that has yet to be surpassed. It was made for peanuts, but Tsukamoto threw every conceivable low-rent special effect into the mix regardless of whether his paltry budget could support it or not.

The film involves a dude (played by Tsukamoto himself) who finds himself transforming into a mutant cyborg: pipes sprout from his body, he hears scraping metallic sounds emit from his girlfriend, and, most distressing of all, his cock turns into a giant buzzing prosthesis. There’s also a mutant cat and another machine guy who shows up to do battle with the protagonist in the mind-rattling climax. TETSUO has been slavishly imitated over the years (as many of the subsequent films on this list prove), but its orgiastic explosion of Giger-esque imagery remains unique.

Tsukamoto returned with the bigger budgeted TETSUO 2: BODY HAMMER in 1991. It’s generally  dismissed by critics, but I quite like it. Despite its flaws, TETSUO 2 is everything we’ve come to expect from Tsukamoto: violent, hallucinogenic and fast!

dismissed by critics, but I quite like it. Despite its flaws, TETSUO 2 is everything we’ve come to expect from Tsukamoto: violent, hallucinogenic and fast!

In a dehumanizing modern metropolis (Tokyo…where else?), a guy finds himself afflicted with strange dreams and visions. When a gang of scumbags kidnap his child, the dude finds the visions becoming reality as his body begins sprouting weird metallic growths. There’s also a man living under the city who leads a bunch of cyborgs-–although just where he leads them I’m not entirely sure. As in part one, the “story” is largely incoherent, but that really doesn’t matter. It’s enough to simply bask in the non-stop barrage of bloody cyberistic visuals.

Tsukamoto’s next film was the even more amazing TOKYO FIST (KOKYO FISUTO), which applied many of themes of the TETSUO flicks to a non-sci fi related tale of body building and unchecked aggression. Another Tsukamoto production worth mentioning is 2003’s A SNAKE OF JUNE (ROKUGATSU NO HEBI), wherein perverse eroticism is utilized in place of TETSUO’S robotic transformations.

Tsukamoto’s next film was the even more amazing TOKYO FIST (KOKYO FISUTO), which applied many of themes of the TETSUO flicks to a non-sci fi related tale of body building and unchecked aggression. Another Tsukamoto production worth mentioning is 2003’s A SNAKE OF JUNE (ROKUGATSU NO HEBI), wherein perverse eroticism is utilized in place of TETSUO’S robotic transformations.

Here we’ll have to take a look back at a much earlier, pre-TETSUO Tsukamoto effort, THE  ADVENTURES OF ELECTRIC ROD BOY (DENCHU KOZO NO BOKEN), which was padded with newly shot footage and released in 1995. The central character of this 40-minute swirl is a man with a rod growing out of his back who finds himself battling a mad scientist and an army of punk vampires intent on taking over the world. He later meets up with another “rod boy” who fills him in on his mission: to save the world and then go forward in time to find his replacement. It climaxes in an astonishing special effects rumble that remains unique in the annals of cult cinema. No, none of it makes much sense, and Tsukamoto’s budgetary deficiencies were evidently far more problematic than in any of his other films, but for sheer mind-bending insanity ELECTRIC ROD BOY nearly equals TETSUO.

ADVENTURES OF ELECTRIC ROD BOY (DENCHU KOZO NO BOKEN), which was padded with newly shot footage and released in 1995. The central character of this 40-minute swirl is a man with a rod growing out of his back who finds himself battling a mad scientist and an army of punk vampires intent on taking over the world. He later meets up with another “rod boy” who fills him in on his mission: to save the world and then go forward in time to find his replacement. It climaxes in an astonishing special effects rumble that remains unique in the annals of cult cinema. No, none of it makes much sense, and Tsukamoto’s budgetary deficiencies were evidently far more problematic than in any of his other films, but for sheer mind-bending insanity ELECTRIC ROD BOY nearly equals TETSUO.

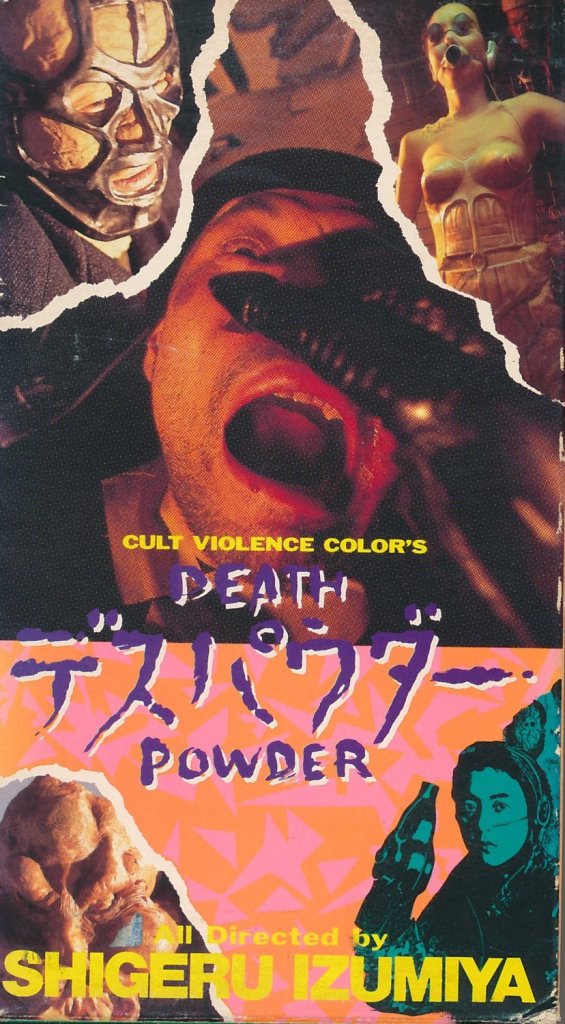

With that I’ll leave Tsukamoto behind and take an even farther look back, into the year 1986. It was then that the deeply trippy DEATH POWDER (DESU PAWUDA) was released, four years before TETSUO officially set the J-cyber perimeters.

With that I’ll leave Tsukamoto behind and take an even farther look back, into the year 1986. It was then that the deeply trippy DEATH POWDER (DESU PAWUDA) was released, four years before TETSUO officially set the J-cyber perimeters.

DEATH POWDER is very much in that tradition, with an android woman known as Guernica laid out in a refuse-littered warehouse, and three mercenaries who try to steal her. They end up inhaling a strange mist emitted by Guernica, which causes them to enter a hallucinatory world ruled by malevolent humanoid creatures (identified by the credits as “Scar People”)-–yet back in the here-and-now the bodies of the mercenaries are mutating into a giant slimy mass.

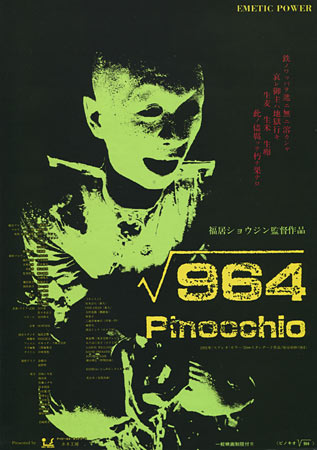

That’s my interpretation, at least. You may feel differently about the events of this profoundly asynchronous collection of sights and sounds that’s quite irritating in some spots and in others plain dull. But it emits a certain crazed fascination, like an out-of-control acid trip, and contains many startling Tsukamoto-worthy sights: an exploding head, metamorphosing bodies and the amazing creature that shows up near the end. Keep in mind that this was all achieved on a shoestring budget and shot on video by punk rocker-turned-experimental filmmaker Shigeru Izumiysa, proving that inspiration and creativity will always be the real special effects. The trend was continued in 1992 with the even-crazier PINOCCHIO 964. It  clearly owes something to TETSUO, and no wonder, as its director Shozin Fukui worked as a production assistant on that film. But Fukui more than came into his own with PINOCCHIO 964, surely one of the greatest Japanese cult films of the nineties.

clearly owes something to TETSUO, and no wonder, as its director Shozin Fukui worked as a production assistant on that film. But Fukui more than came into his own with PINOCCHIO 964, surely one of the greatest Japanese cult films of the nineties.

Pinocchio 964 is a sex android who’s lobotomized and loosed on the streets of Tokyo. He takes up with a nutty street chick who promptly goes mad; she tortures Pinocchio and chains him up just as Pinocchio’s creators launch a hunt for him. This leads to an unspeakably over-the-top nightmare of blood, slime and sheer insanity. Taken as a whole, the film is an astonishingly assured cavalcade of psychotic mayhem. Fukui’s unhinged cinematics—unfettered handheld camerawork, a wildly unpredictable editing scheme, hysterical acting—perfectly compliment the schizophrenic narrative. That’s in addition to a veritable smorgasbord of grue, with copious bodily fluids and possibly the most prolonged vomiting sequence ever.

But what ultimately makes the film distinctive is Fukui’s filmmaking brilliance. He creates images as memorable and disturbing as those of Tsukamoto, Andrzej Zulawski and David Lynch, all of whom PINNOCHIO 964 recalls…yet there’s ultimately nothing else like it.

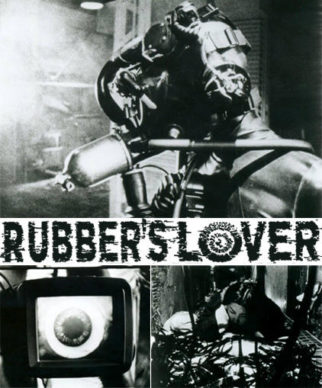

The black and white RUBBER’S LOVER was Fukui’s similarly themed 1997 follow-up, and it’s a bit of a let down—but not an unworthy movie! It concerns an experiment into psychic potential that takes place in a forbidding warehouse. There several nutcase scientists inject people with the drug ether and bombard them with loud noises. But when the experimenters unwisely kidnap an attractive secretary their subjects go nuts, unleashing a blast of gory mayhem: we see a woman graphically disemboweled, a guy puke his guts out and a lesbian literally devours her fuck mate.

The black and white RUBBER’S LOVER was Fukui’s similarly themed 1997 follow-up, and it’s a bit of a let down—but not an unworthy movie! It concerns an experiment into psychic potential that takes place in a forbidding warehouse. There several nutcase scientists inject people with the drug ether and bombard them with loud noises. But when the experimenters unwisely kidnap an attractive secretary their subjects go nuts, unleashing a blast of gory mayhem: we see a woman graphically disemboweled, a guy puke his guts out and a lesbian literally devours her fuck mate.

Despite all this RUBBER’S LOVER, unlike its predecessor, doesn’t really stand out amidst the other films described herein. Again, though, that doesn’t mean it’s bad: it adequately showcases its creator’s gift for extreme cinema, and has an authentically demented edge.

The years 1990-95, when Tsukamoto and Fukui made their signature films, can be viewed as the golden age of the J-cyber tradition. (Some characterize the 1993 Toho production ROBOKILL BENEATH DISCO CLUB LAYLA, 1996’s ORGAN, from TETSUO co-star Kei Fujiwara, the 1997 FULL METAL YAKUZA and the futuristic no-budgeter HELLAVATOR: THE BOTTLED FOOLS, from 2003, as belonging to the cycle.) That was before the “J-horror” craze overtook Japanese genre cinema with a slew of formulaic horror movies patterned after the mega-successful RINGU (1996). But you can’t keep a good sub-genre down for long.

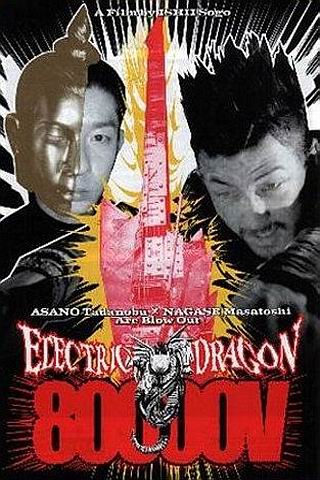

Just take a look at ELECTRIC DRAGON 80.000v from 2000, a 55-minute minute blast of unfettered cinemadness from cult legend Sogo Ishii. It  appears to have been inspired by the work of Tsukamoto and Fukui, but Ishii was in fact making films long before them, and can be seen as one of the primary influences on the J-cyber cycle.

appears to have been inspired by the work of Tsukamoto and Fukui, but Ishii was in fact making films long before them, and can be seen as one of the primary influences on the J-cyber cycle.

Lensed in luminous black and white, ELECTRIC DRAGON 80.000v is about a guy who as a child was zapped with electricity, which somehow granted him supernatural powers. As an adult he undergoes a number of painful tests by demented researchers before meeting up with another guy possessing similar powers, and the two inevitably square off in an electricity-powered showdown. With its unrestrained camerawork and frequent video game inspired effects, this is fun stuff, even if it ultimately brings little to the table that Tsukamoto didn’t already.

The same is true of TSUBURO NO GARA from 2004. The debut film of writer-director Masafumi Yamada, it’s far more dreamy and contemplative in its construction than the preceding films. Featured are a nondescript man and woman awakening in a claustrophobic enclosure of rooms and tunnels; the woman tries every way she can to break out while the man, sporting an unidentified metal contraption on his back, hallucinates wildly. Inevitably these two basket-cases have sex, which only heightens their desperation. No, there’s no real resolution in store in this 68-minute film, which despite intriguing touches is a bit too slight for its own good.

And with that this list comes to an end, but definitely not the sub-genre overall.

The influence of TETSUO, PINOCCHIO 964 et al continues, and has spread outside Japan: witness the Korean KILLING MACHINE (DAEHEKNO-YESEO MAECHOON-HADAKA TOMAKSALHAE DANGHAN YEOGOSAENG AJIK DAEHAKNO-YE ISSDA) from 2000 and the American SIXTEEN TONGUES from 2005, two deranged exercises in cyberistic psychosis that bear the unmistakable J-cyber stamp. This particular subgenre hasn’t seen its last days, and surely (I’m hoping) has a way to go yet. Here’s to iron men, rod boys, scar people and electric dragons. Long may they vomit, bleed, disgust and delight!