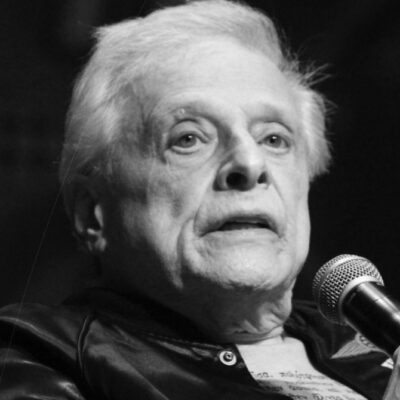

It’s been six years since the June 28, 2018 demise of Harlan Ellison. The man, as I’m sure most of my readers are aware, was a highly contentious figure in his lifetime and remains so after his death. Has he attracted a new generation of fans? Not really. Ellison’s legacy, in truth, was best summed up by a self-penned epitath: “For a brief time I was here, and for a brief time I mattered.” An egotistical summation, certainly, but also an admirably blunt assessment of the limits of fortune: Ellison may indeed have mattered, but only for a brief period.

In 2024, however, Harlan Ellison returned to public consciousness. That return consisted of assorted mentions on YouTube inciting renewed interest and the release of a long-awaited book that assumed the status of an Important Event in the science fiction field.

HARLAN ELLISON’S VIEWS ON STAR WARS (1978)

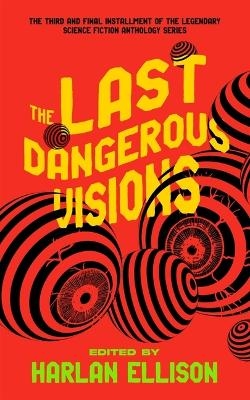

I’m referring to THE LAST DANGEROUS VISIONS, an anthology that’s been in the works for over fifty years. The final entry in a series that began with the Ellison edited DANGEROUS VISIONS in 1967, and continued with AGAIN, DANGEROUS VISIONS in 1972, THE LAST DANGEROUS VISIONS, initiated in 1973, was intended to finish things out on a high, and quite lengthy, note. Perhaps inevitably, the project grew out of Ellison’s control, which didn’t stop him from continuing to buy stories for it throughout the 1980s, 90s and beyond.

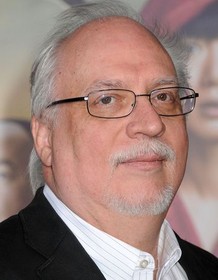

It was BABYLON 5 creator J. Michael Straczynski, Ellison’s literary executor, who revived THE LAST DANGEROUS VISIONS (Straczynski, in addition to handling Ellison’s literary output, took ownership of his Sherman Oaks house, and plans on turning it into a museum) and ultimately completed the project. Correction: Straczynski “completed” it, as the LAST DANGEROUS VISIONS published on October 1, 2024 can’t truly be called Ellison’s work.

Straczynski, after all, provided introductions for nearly all the stories and (as he admits in a lengthy afterward) selected which of the Ellison commissioned entries made the final cut and personally solicited several new ones. The result is a disjointed mixture of old and new, liberal and progressive, “Dangerous” and safe, Ellison and Straczynski—with the latter, in all cases, ultimately winning out.

In fairness, THE LAST DANGEROUS VISIONS would have likely been a disappointment in any form. If Straczynski’s afterword is to be believed, no “original, locked-down, written-in-stone, no-seriously-this-is-it-for-sure version” ever existed, and of the 120-plus stories Ellison procured (he apparently “bought stories for TLDV the way most people eat potato chips”), many were purchased simply as favors for his writer friends. Others, such as a story by the late Octavia Butler, ended up being published elsewhere, while a submission from the late Vonda McIntrye was withdrawn by her surviving relatives. Straczynski is upfront about the no-win situation in which he was placed, admitting “Whichever way I went, I was going to get yelled at by someone, and most annoying of all, they would be absolutely correct in doing so.”

The best part of the book, if you ask me, is Straczynski’s introductory essay “Ellison Exegesis.” It’s a lengthy recounting of Straczynski’s relationship with Ellison, with biographical details that don’t appear anywhere else (including Nat Segaloff’s celebrated Ellison bio A LIT FUSE). We learn that Ellison’s overbearing and obnoxious nature, about which Straczynski is admirably up-front, came from a very real mental condition: bipolar disorder, with which he was formally diagnosed near the end of his life. We also learn that those final years were deeply harrowing, involving marital strife, multiple instances of indecent exposure, much compulsive spending, a suicide attempt and confinement in a mental hospital.

Among the highlights of the first two DANGEORUS VISIONS were Ellison’s quirky introductions (in which he invariably wrote as much about himself as he did the author and story at hand). For THE LAST DANGEROUS VISIONS Ellison only managed to complete one such introduction, for “War Stories” by his longtime pal Edward Bryant, and that preamble isn’t very strong (taking the form of an extended apologia for including an author who was already represented in one of the previous volumes). Bryant’s story isn’t much better, being a millennia-spanning account of sharks, human made and otherwise, that was for some reason divided into six chapters (five too many) and contains stylistic quirks that may have seemed innovative back in the seventies, but come off as tiresome and self-indulgent in 2024 AD.

Of the other Ellison vetted stories, “Assignment No. 1” by the late Stephen Robinett is a compelling but far from exceptional (much less dangerous) story about a tank farm in which old people are consigned, not always willingly, to live in virtual reality netherworlds. “None So Deaf” by Richard E. Peck is on the same tier quality-wise, with a grief-stricken man going deaf and developing an entirely new, and perhaps supernaturally enhanced, understanding of reality (I’d recommend reading AGAINST GOD by Patrick Senecal to see precisely what Mr. Peck was attempting).

“The Final Pogrom,” by Ellison’s major 1980s “discovery” Dan Simmons, is among the better entries. Concerning a pogrom against Jewish citizens in a post-pandemic America, the story is arguably more relevant now than it was during its mid-1980s inception. That’s also the case with “The Malibu Fault” by Jonathan Fast, a once-science fictionish offering about a retired, and very liberal, screenwriter concerned that his paradisal existence in Malibu will be disrupted by the encroachment of a lower class “They,” i.e. the very people he claims to support. Ellison also purchased a story by Jonathan Fast’s father Howard: “The Size of The Problem,” a diverting, if slight, dream-within-a-dream-within-an-alternate reality narrative.

Continuing with the Ellison procured tales, “Goodbye” by Steven Utley is a slight account of a woman left behind by a time traveler, and the personal devastation that results. “Rundown” by John Morressy is an enjoyable bit of weirdness described by Straczynski as “an utterly charming but quite mad digression into geopolitical whatthefuck,” while the over-before-you-know-it “Men in White” by David Brin, about aliens attempting to make their presence known to Earthlings, is too short to make much of an impression.

It comes as no surprise that many of Ellison’s 1970s-era commissions now seem pretty stodgy. That’s true of “The Time of the Skin” by the late A.E. Van Vogt, about aliens and skin swapping, and “Falling From Grace” by Ward Moore, a thoroughly archaic bit of dystopian humor of a type introduced in its author’s most famous work, the novel BRING THE JUBILEE, which was published back in 1953. Two more for the stodgy category are “Primordial Follies” by Robert Sheckley, a bit of throwaway silliness about a “hetero-eater” who consumes most of the known universe, and “The Danann Children Laugh” by Mildred Downey Broxon, a darkly whimsical account of a most unique child’s fate in modern-day Ireland.

Of the Straczynski commissions, at the forefront is “Hunger” by Max Brooks, a hectoring political screed that just barely qualifies as science fiction—and is the closest this book comes to being truly “Dangerous.” Related in the form of a lengthy missive by a Chinese official to the President of the United States, it’s ostensibly about political blackmail, with the actual subject being the apathy and ignorance of America’s populace, as exemplified by the Thomas L. Friedman quote “In China, Bill Gates is Britney Spears. In America, Britney Spears is Britney Spears.”

Other Straczynski buys include “The Great Forest Lawn Clearance Sale—Hurry, Last Days!” by Stephen Dedman, which boasts a great, if underutilized, concept involving a cloning service whose subjects include Jesus Christ. “After Taste” by Cecil Castellucci is about a lesbian food critic on a distant planet that boasts “the rarest meals in the galaxy in abundance”; the protagonist is served an especially rare dish that leads to no less than three twists, two of which are satisfying. “Leveled Best,” the first published story by Steve Herbst, is a(nother) variation on the (over)tried and (no longer) true Orwellian future trope. Another first timer is Kayo Hartenbaum (identified by Straczynski as an “up-and-coming genderqueer author”), who provides “Binary System,” a tortured, and not very entertaining, rumination on solitude and otherness.

“The Weight of A Feather (The Weight of A Heart)” by Cory Doctorow offers an overtly literary take on a future “retreat” where wrongdoers are consigned, with the focus on a couple and their robot companion. D.M. Rowles (a.k.a. Deborah Shepard) provides eight evocative but forgettable mini-stories that fall somewhere between prose poetry and narrative speculation, presented in the form of transitional “Intermezzos.”

The final entry, “Judas Iscariot Didn’t Kill Himself: A Story in Fragments” by James A. Corey (a.k.a. Daniel Abraham and Ty Franck), deserves some in-depth coverage. According to Straczynski, “Of all the stories that appear in this volume, what follows may be the most dangerous of all, dealing with controversial subjects that will doubtless provoke heated debate.” Involving body switching amid the members of a cult-like consortium, the story breaches controversial topics, such as bigotry and child molestation, but they’re handled in a tasteful and non-explicit—and, hence, dull—manner.

Diverting, slight, stodgy, hectoring, literary and dull are the major adjectives I’ve utilized in describing these stories, which make for a worthwhile, if extremely uneven, volume. My major complaint, as stated above, is with the “Edited By” credit, which should have been given to J. Michael Straczynski, or perhaps “Harlan Ellison and J. Michael Straczynski,” rather than Ellison getting sole billing. Doing so may be interpreted as an act of generosity on the part of Straczynski, but I believe in giving credit where credit is due.

See Also THE LAST DANGEROUS VISIONS: Anatomy of a Non-Publication; VIC, BLOOD, AND HARLAN