According to artist/writer/editor Stephen R. Bissette, in the 1980s he was “frustrated over the fact that a boom period for horror was occurring, but comics seemed uninvolved in this renaissance.” That situation changed quite dramatically in the ‘90s and ‘00s, due in no small part to the Bissette edited horror-themed comic anthology series TABOO, which began in 1988 and lasted nine issues (and one “Especial”). It proved more influential than anyone could have suspected, with a mission statement—“We want the deepest, darkest stuff we can come up with. We want you to, to paraphrase David Cronenberg, ‘speak the unspeakable and show the unshowable’”—that adequately summed up the sentiments behind the innumerable horror comics that followed.

Those comics were often, like TABOO, adult-oriented horror anthologies. The similarly minded (but less potent) FLY IN MY EYE, which got started by Arcane around the same time as TABOO, was one such example. TAPPING THE VEIN (1989-92), an Eclipse published five volume compilation of Clive Barker adaptations, was another. There was also Studio Insidio’s four issue FROM BEYONDE from 1991, and Dark Horse Comics’ BY BIZARRE HANDS, a three issue series of Joe Lansdale adaptations from 1994 (revived by Avatar Press in 2004). J.N. WILLIAMSON’S MASQUES (Innovation; 1992) managed two issues, while the same year’s John Skipp and Craig Spector showcase comic MALFORMED (Black Eyed Books) managed a single issue, as did the following year’s John Bergin and James O’Barr edited BONE SAW (Tundra).

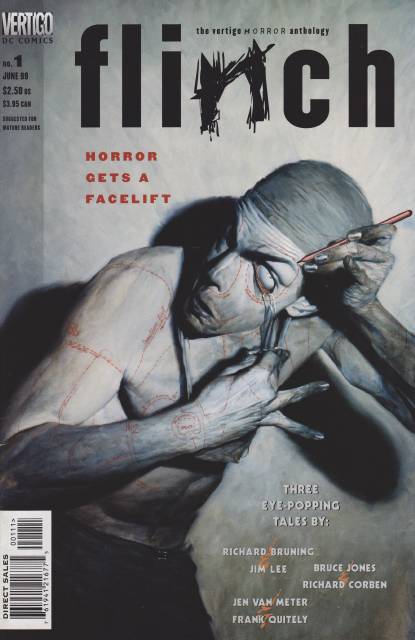

It was also in 1993 that the DC Comics imprint Vertigo got started (with the Neil Gaiman scripted SANDMAN spin-off DEATH: THE HIGH COST OF LIVING), and it was under Vertigo’s auspices that the ambitious horror anthology series FLINCH appeared in 1999.

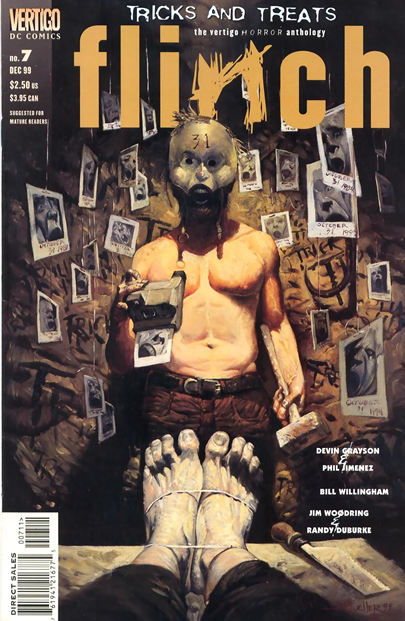

Proclaiming itself “An unprecedented gathering of fever dreams and waking nightmares scraped from the darkest corners of the greatest minds in comics,” FLINCH garnered a great deal of praise from various industry luminaries, and some prestigious awards. Sales, however, were far from spectacular, and Vertigo’s higher-ups reportedly weren’t too happy with it. FLINCH ultimately folded in January 2001, after just 16 issues.

Reading through FLINCH’s contents (which were collected in two volume graphic novel form in 2015 and ‘16), consisting of three tales per issue, each scripted and illustrated by different people, it’s impossible not to be struck by the range of artwork and subject matter. It is, perhaps inevitably, quite an uneven compilation; some of the stories contained in FLINCH are good and some not-so, while there are a few entries that can be classified as great.

One especially striking element is the gorgeous cover art. Accomplished by artists ranging from Phil Hale to Richard Corben and Kent Williams (all big names in the comic book field), FLINCH’s covers, with their gaudy images of a man peeling back his eyelid to expose an all-white eyeball (with the accompanying caption “Horror gets a Facelift”), a guy seated on a burning couch, a dog with a woman’s face and a girl holding a cockroach-ridden skull, were often more striking than the interior content.

One especially striking element is the gorgeous cover art. Accomplished by artists ranging from Phil Hale to Richard Corben and Kent Williams (all big names in the comic book field), FLINCH’s covers, with their gaudy images of a man peeling back his eyelid to expose an all-white eyeball (with the accompanying caption “Horror gets a Facelift”), a guy seated on a burning couch, a dog with a woman’s face and a girl holding a cockroach-ridden skull, were often more striking than the interior content.

Regarding that content, several top names, such as Alan Moore, Grant Morrison and Neil Gaiman, were left out of its line-up, but the “greatest minds in comics” claim was accurate enough. The writers included big names like Bruce Jones, Joe Lansdale, Garth Ennis, Mike Carey and Ted McKeever, and the artist lineup featured the equally iconic likes of Richard Corben, Ted McKeever, Timothy Truman and Bernie Wrightson. Clearly FLINCH’s editors—who included Axel Alonzo (of DOOM PATROL and ANIMAL MAN), Joan Hilty (who accepted FLINCH’s 1999 International Horror Guild award) and Vertigo’s founder Karen Berger—weren’t fooling around.

The influence of EC Comics is evident in quite a few of the stories. One is “You’ve Got Hate Mail!,” written by Robert Rodi and illustrated by Marcelo Frusin, containing what in the early ‘00s might have seemed a fresh approach: an internet-based horror story, involving a jilted woman using the net to get revenge on a playboy. Revenge, of course, was an EC staple, and this particular tale never quite transcends the appealing but done-to-death EC formula. Ditto “Night Terrors” by John Rozum and Kelley Jones, and “Fumes” by Mark Wheatley and Marc Hempel, both of which are very EC-ish.

But enough negativity. Let’s concentrate on the good stuff, which includes the Bram Stoker Award winning “Red Romance” by writer Joe R. Lansdale and artist Bruce Timm, a sickie about a psychopathic couple attempting to rekindle their moribund marriage; it’s easily one of FLINCH’s nastiest entries, although the black humor and highly exaggerated, cartoony artwork take the edge off (see also the Lansdale scripted, Rich Burchett rendered “Betrothed,” involving a serial killer, a necrophile priest and their competing moralities). “The Day Wife,” written and illustrated by Phillip Hester, is a genuinely eerie and perverse account of a man who discovers that his wife has a “day” and “night” side, with the latter consisting of a blue-tinged humanoid possessed of amazing sexual prowess. Then there’s “The Harvester” from scripter Thom Metzger and drawer Sean Phillips, which works because the horror it presents, in its depiction of an organ harvesting team’s nightly doings, is entirely free of the supernatural yet still registers as profoundly ghoulish and horrific.

Issue #12’s “Watching You,” with writing by Bruce Jones and art by Frank Quitely, depicts a perverse three-way  relationship between a skinny nerd, his high school crush and a war veteran bully who’s incapable of performing sexually, that’s reminiscent of Jones’ infamous 1984 TWISTED TALES contribution “Shut In” (truthfully I can think of no higher praise). Issue #10’s “The Mule” by Tony Bedard and David Lloyd is even stronger, being a harsh yet poignant account of a desperate woman smuggling contraband inside the corpse of a dead baby (which may not be entirely dead). Issue #8’s “The Toy,” from Jim Woodring and Randy DuBurke, is as overtly trippy as just about anything you’ll find, with artwork that makes excellent use of POV shots and other cinematic visual quirks.

relationship between a skinny nerd, his high school crush and a war veteran bully who’s incapable of performing sexually, that’s reminiscent of Jones’ infamous 1984 TWISTED TALES contribution “Shut In” (truthfully I can think of no higher praise). Issue #10’s “The Mule” by Tony Bedard and David Lloyd is even stronger, being a harsh yet poignant account of a desperate woman smuggling contraband inside the corpse of a dead baby (which may not be entirely dead). Issue #8’s “The Toy,” from Jim Woodring and Randy DuBurke, is as overtly trippy as just about anything you’ll find, with artwork that makes excellent use of POV shots and other cinematic visual quirks.

And we mustn’t forget “El Orgo” from Ivan Velez, Jr. and Ho Che Anderson. An odd and troubling little piece about an obese man traumatized by his brother’s untimely death, it makes its points through a strongly evoked sense of grief and disillusionment rather than surface-level gore and disgust (although it does contain a goodly amount of the latter element), and is rendered through strikingly primitivistic artwork.

Not quite as potent, but still memorable, entries include “Found Object,” written by Bob Fingerman and illustrated by Pat McEown. The artwork on this one isn’t too exciting, but conceptually it’s quite brilliant, with a young woman picking up Polaroids left scattered throughout a city, the reason for which is explained on the final page. “Dead Woman Walking,” written and illustrated by William Messner-Leobs, contains some truly mind-scraping conceptions that, as with “Found Object,” aren’t matched by the artwork. The Brian Azzarello scripted “Last Call” is notable for the unforgettably lurid, noirish artwork by Danijel Zezelj that, for once, far outdoes the story. “Mostly White” by Bruce Jones and Dave Taylor is a Christmas-themed tale, visualized in bright, non-confrontational shapes and colors that are redolent of a happy fantasy that’s anything but happy.

So on balance FLINCH adds up to a terrific batch of pictorial horror, and a fine addition to its publisher’s distinguished line-up. Vertigo, incidentally, was discontinued in 2020, marking a true end of an era. FLINCH may not be among Vertigo’s greatest publications (it will never supplant THE SANDMAN or SAGA OF THE SWAMP THING), but it is an undoubted standout.